Stop anonymous callers who are weaponizing NY’s child abuse hotline (Editorial Board Opinion)

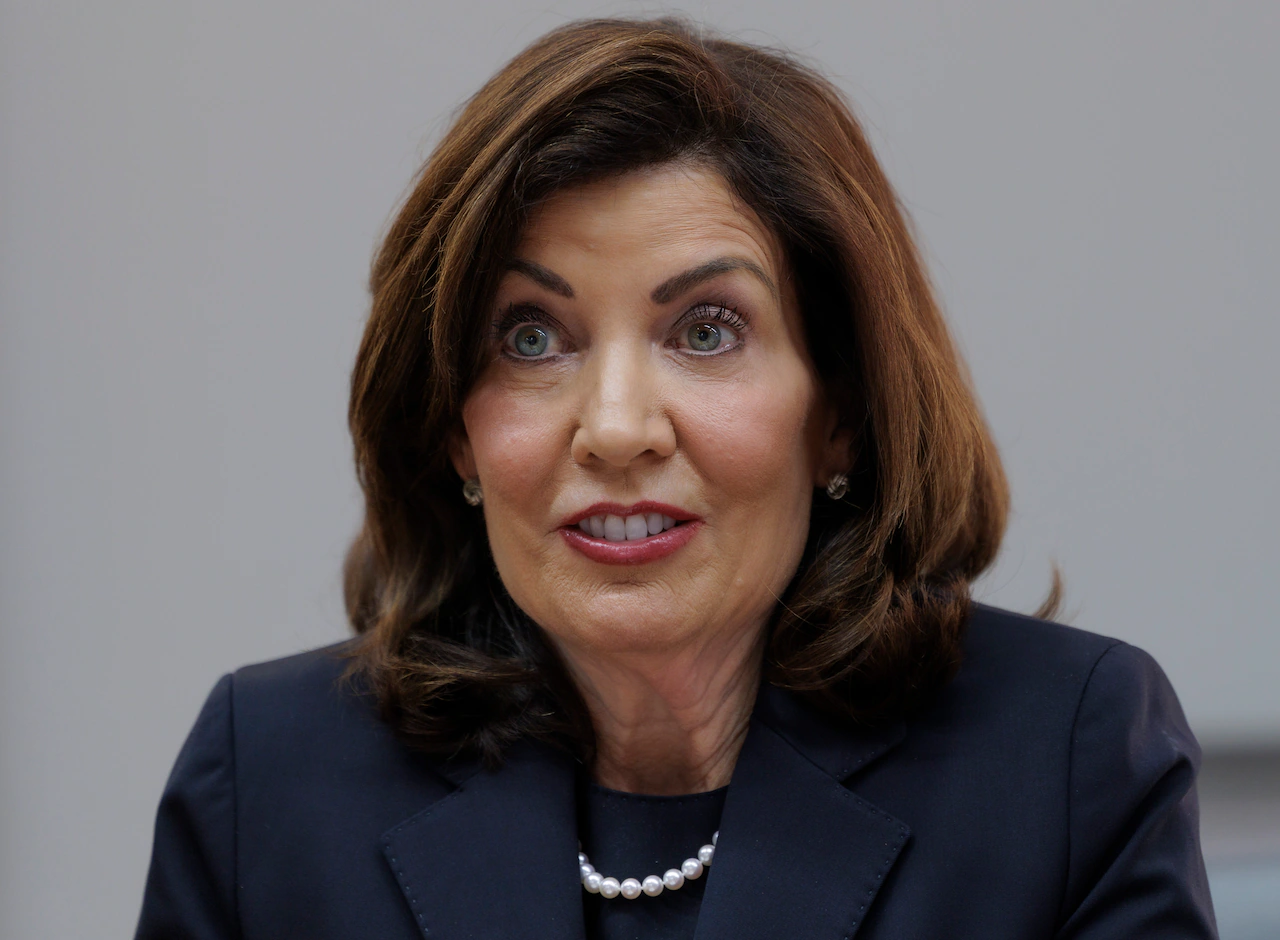

Gov. Kathy Hochul should sign legislation that would end anonymous reporting of child abuse to the state hotline, and instead require callers provide their names on a confidential basis.

Statewide, anonymous reports accounted for only 7% of the 150,000 calls made on average each year to the state hotline, according to 2022 data. Up to 96% of those anonymous reports turn out to be unfounded, according to the bill’s sponsors.

Often, they are maliciously filed by exes, abusive partners, neighbors and landlords. In the course of investigating even meritless complaints, children and caregivers could be traumatized by intrusive searches. Families can be torn apart.

Meanwhile, scarce child protective resources are spent sorting the legitimate reports from the harassing ones.

Child welfare investigators are hamstrung by anonymous reports. They are required to investigate but only get one side of the story from the person anonymously accused of abuse. They can’t go back to the caller for more information.

It has long been a crime to falsely report child abuse. That is hardly a deterrent. Without a name attached to the report, prosecutors have no way of filing charges.

Ending anonymity in child abuse reporting does not mean the names of callers will be released to the public or to the alleged child abusers. The bill requires that their names remain confidential, subject only to release by a judge’s order under extenuating circumstances. The law would allow the state to keep the information secret if it is likely to endanger the life of the person who reported the suspected abuse.

This change also would not affect “mandatory reporters” — teachers, social workers and doctors who are required to report child abuse. They already have to provide their names, which are held in strict confidentiality.

Critics of the legislation — including Hochul’s own commissioner of the Office of Child and Family Services — say ending anonymous reporting carries the risk of deterring someone from reporting a real case of child abuse. Others worry that the bill lacks guardrails to protect siblings, victims of domestic violence or close neighbors from retaliation.

OCFS should be ready to explain what confidentiality means to hotline callers and allocate proper resources to protect their identities. A public education campaign assuring callers their names will be shielded might allay some misgivings.

Of course, we would expect that someone who has gone to the trouble of calling the state hotline about a child in danger would not be so easily deterred.

Some perspective is useful. Over the years, syracuse.com has reported on (and the editorial board has bemoaned) too many cases of child abuse that ended in the tragic and preventable deaths of children. All of them were well-known to child welfare agencies in their communities. The failures were in the follow-through, not the reporting.

Our hope is that by reducing the number of false reports, child protective workers can focus their energies on preventing these tragic outcomes.

About Syracuse.com editorials

Editorials represent the collective opinion of the Advance Media New York editorial board. Our opinions are independent of news coverage. Read our mission statement. Members of the editorial board are Tim Kennedy, Trish LaMonte and Marie Morelli.

To respond to this editorial: Submit a letter or commentary to letters@syracuse.com. Read our submission guidelines.

If you have questions about the Opinions & Editorials section, contact Marie Morelli, editorial/opinion lead, at mmorelli@syracuse.com