Copyright The Austin Chronicle

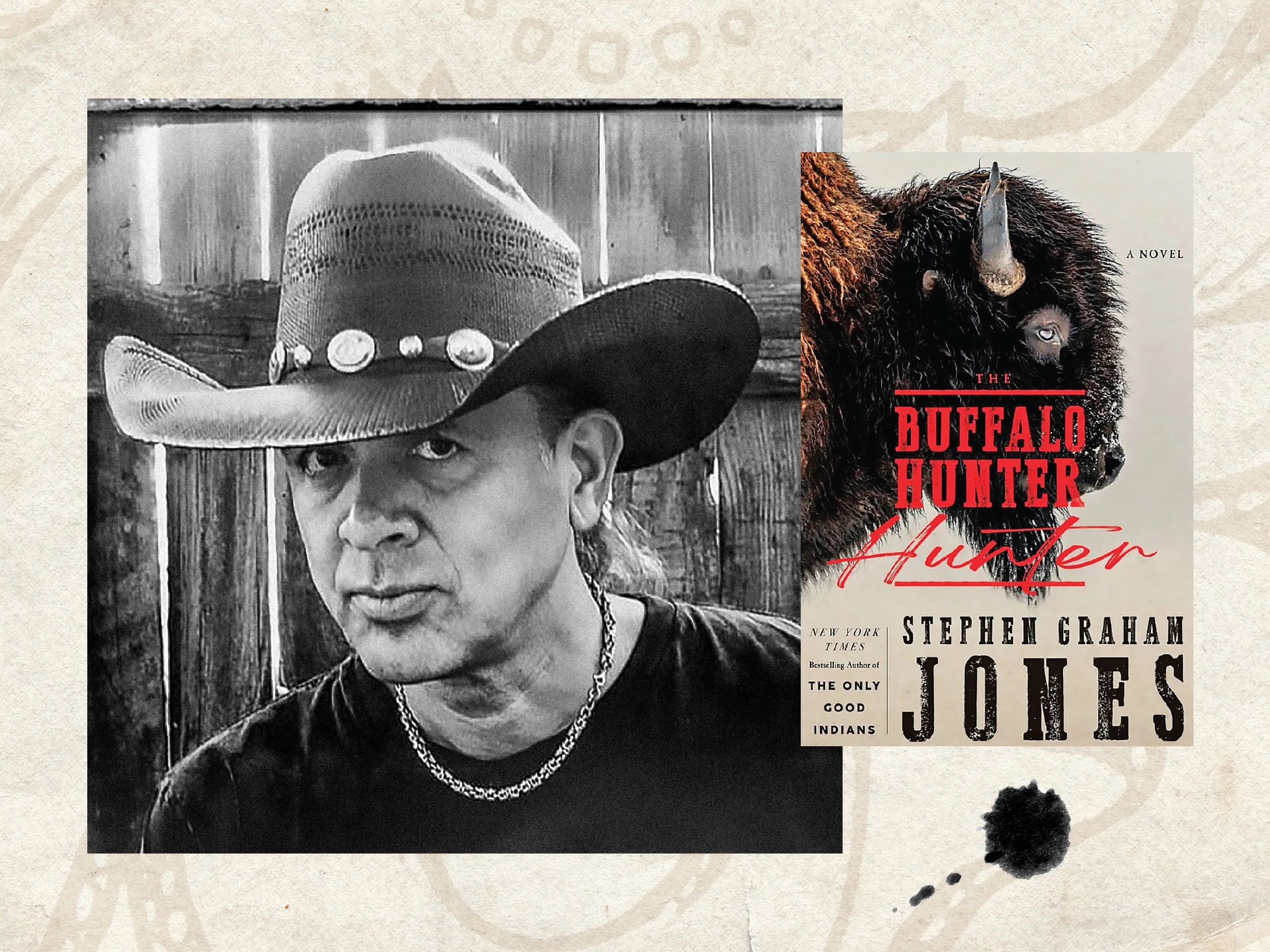

“If I were a vampire, I could do it better,” promises Stephen Graham Jones. The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, a historically bound horror tale, is his proof of concept. The Blackfeet writer has built his reputation on slashing horror tropes, disfiguring genre conventions, and summoning monsters that struggle with their own significance. “For me to believe in the vampire, enough to invest intellectually and emotionally in it for 450 pages, I had to make it a believable creature for me,” Jones says. For the prolific novelist, whose bestsellers include The Only Good Indians and My Heart Is a Chainsaw, this meant stripping a centuries-old creature of many of its contradictory features, contrived over the fabled figure’s long shelf life and many reincarnations. “You have this amalgamation of a monster that has all these characteristics that don’t necessarily complement each other,” Jones explains – no telepathy or mist shapeshifting for him, and no sultry cigarette smoking either. His Western-roaming ghoul plays by different rules, inherent to his specific background and the customs of his culture. Enter Good Stab, a bloodsucking Blackfeet native driven by a gluttony so extreme that he bursts his own stomach open, compelled to drink every last drop of his prey’s blood. In the early days of the American West, Good Stab hunts alongside his people, longing to protect them from the colonizers encroaching on Blackfeet Nation. “He both doesn’t respect the American flag and he doesn’t respect the Christian crucifix, and the reason for that is his people have had bad histories with each of those,” Jones says, illustrating another deviation from vampiric canon that felt essential for his take on the creature. Another sticking point: Good Stab’s vampirism is no superpower. The fanged fiend takes on the characteristics of those he feeds on, sprouting the antlers and whiskers of animalistic prey and, crushingly, losing his heritage when he victimizes the white pioneers terrorizing his tribe. Jones’ monster must ultimately kill those he wishes to defend in order to maintain his Native American identity. “For a long story to have the kind of conflict that [it] needs to drive it, that conflict needs to be basically unsolvable,” the author says. Good Stab’s ultimately eternal struggle with the curse of his condition comes to life in confessional chapters transcribed from the creature’s spoken retellings. Though Jones had long wanted to write a vampire like Good Stab, calling him a “wish fulfillment character,” putting his vision to paper was a challenge. “He was the hardest character for me to inhabit,” he says. His Western upbringing did him few favors when it came to possessing a character immersed in an oral storytelling tradition and spiritual worldview that has since been forcibly altered by centuries of genocide and colonization. “The world he lives in, that he grew up in, that he knows, does not distinguish between the natural and the supernatural even a little bit,” he explains. The more Jones wrote as Good Stab, the more he felt his monster come to life. “His worldview and his mindset came out of his diction for me,” he says. Ultimately, trusting the performative nature of the creature’s voice let Jones become the vampire of his dreams – or, rather, nightmares. This article appears in November 7 • 2025.