Solar storms—giant bursts of energy from the Sun that disturb the Earth’s magnetic field—may play a role in triggering heart attacks, particularly in women, a new study has found.

Researchers led from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) analyzed hospital records from São José dos Campos, Brazil, between 1998 and 2005—a period marked by high solar activity.

Specifically, the team compared 1,340 heart attack cases (reported among 871 men and 469 women) with data on variations in the strength of Earth’s magnetic field, as measured using the so-called Planetary Index (Kp-Index).

“We classified the days analyzed as calm, moderate, or disturbed. And the health data were divided by sex and age group [up to 30 years old; between 31 and 60; over 60 years old]. It’s worth noting that the number of heart attacks among men is almost twice as high – regardless of geomagnetic conditions.

“But when we look at the relative frequency rate of cases, we find that for women, it’s significantly higher during disturbed geomagnetic conditions compared to calm conditions. In the 31-60 age group, it’s up to three times higher,” said paper author and INPE researcher Luiz Felipe Campos de Rezende in a statement.

“Therefore, our results suggest that women are more susceptible to geomagnetic conditions,” Rezende added.

What’s Going On in the Atmosphere?

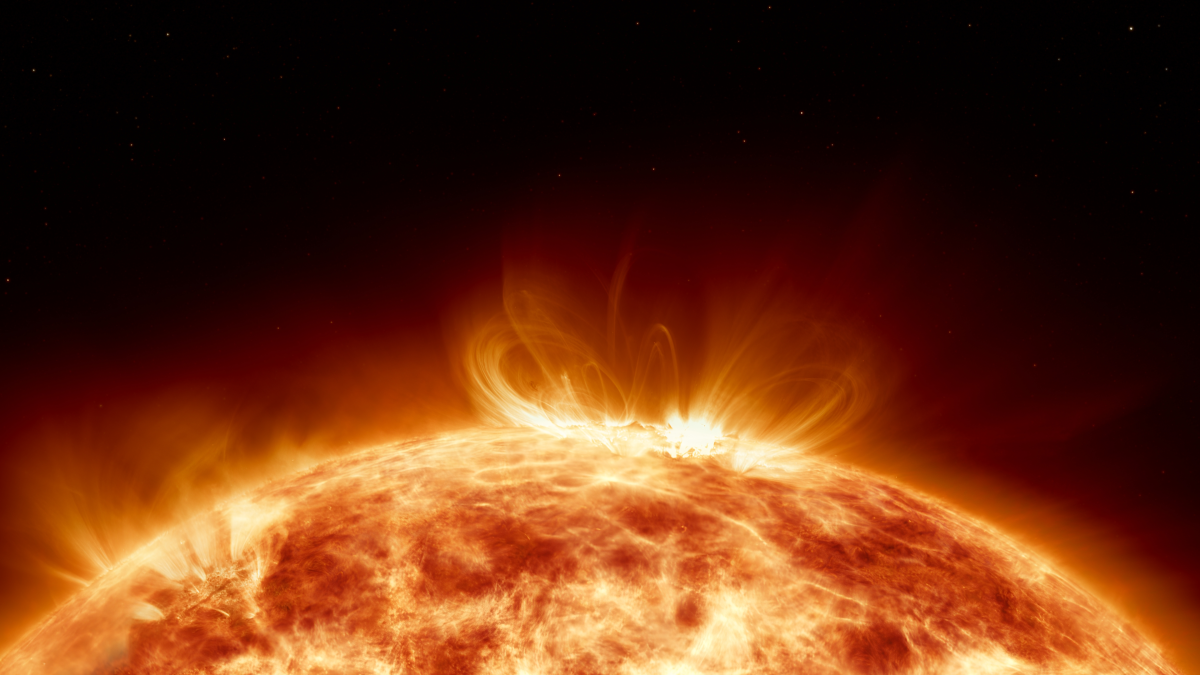

Geomagnetic disturbances happen when the solar wind—the constant stream of charged particles from the Sun—collides with Earth’s magnetic field. These events can disrupt satellites, radio signals and GPS.

Since the late 1970s, studies in the Northern Hemisphere have hinted that these solar particles might also affect human health, particularly the heart.

Possible explanations include changes in blood pressure, heart rate and even circadian rhythms (the body’s natural sleep-wake cycle). Still, scientists stress that this connection is far from proven.

First of Its Kind in Brazil

“This is the first study on the subject conducted in our latitudes, but it isn’t conclusive. Therefore, the intention isn’t to cause alarm among the population, particularly among women,” Rezende said.

There are some limitations to consider: this is an observational study conducted in a single city, using a sample size that isn’t yet ideal for medical questions.

“However, we believe that these findings represent an empirical result of hypothetical significance and relevance that shouldn’t be disregarded in the scientific context.”

The findings also suggest women might be more vulnerable to geomagnetic disturbances than men—something that hasn’t been widely documented before.

“We didn’t find any significant publications on this subject in the literature. It’s a question for future studies,” Rezende added.

Looking Ahead

The Sun operates on roughly 11-year cycles of high and low activity. The current cycle reached its “solar maximum” in late 2024 and early 2025, meaning solar storms are more likely over the next year. INPE and other space agencies monitor these disturbances, but predicting exactly when they’ll hit remains difficult.

“Scientists around the world have been trying to predict the occurrence of geomagnetic disturbances, but the accuracy, for now, isn’t good. When this type of service is more advanced – and if the impact of magnetic disturbances on the heart is confirmed – we’ll be able to consider prevention strategies from a public health perspective, especially for individuals who already suffer from heart problems,” Rezende said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about the Earth’s magnetic field and heart attacks? Let us know via health@newsweek.com.

Reference