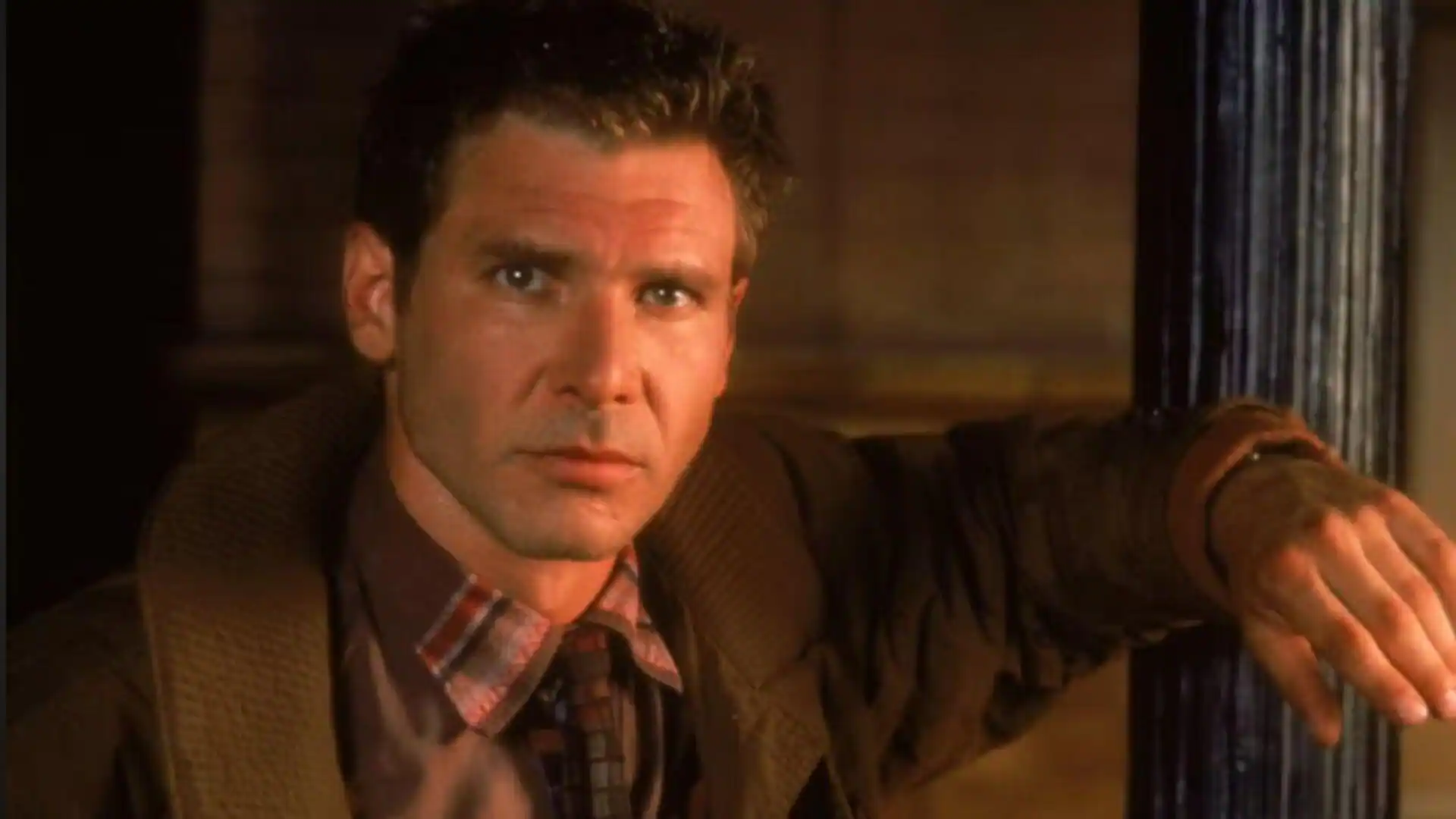

It’s easy to dismiss the women on the Real Housewives franchise as out of touch or unrelatable. But between private-jet flights to Spain and shopping sprees on Rodeo Drive, these women still deal with problems that affect millions of women worldwide.

On the recent season of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, newcomer Bozoma Saint John shared her own struggle after the surgical removal of fibroids, which are non-cancerous growths that develop in a woman’s reproductive tract.

Saint John wasn’t the first to speak about this condition, as housewives from New York, Potomac and Atlanta also have shared their journeys through the years. But while these shows have been praised for bringing awareness to the condition, women shouldn’t learn about this common health problem from reality TV.

By the age of 50, 65 to 70 percent of women will have uterine fibroids, Dr. Erica Marsh of University of Michigan Health, told Newsweek in an interview. This amounts to about 26 million women in the U.S., according to the National Institute of Health (NIH). The disease is much more common and more severe for Black women, who are three times more likely to be diagnosed with fibroids than white women.

“There are very few things more prevalent than [fibroids],” she said. “When you have a disease as prevalent, even if half or a quarter of [women with fibroids] are symptomatic, that’s still millions of women.”

While not life-threatening, fibroids can cause severe pain, potential infertility and organ damage, depending on their size and location. Women can develop multiple symptoms, like heavy menstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, frequent urination, constipation and back pain.

Newsweek recently published its ranking of the World’s Best Specialized Hospitals 2026, which features hundreds of hospitals around the world in 12 medical specialties, including obstetrics and gynecology. Top facilities include Johns Hopkins Hospital in the U.S., Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli in Italy and The University of Tokyo Hospital in Japan.

Diagnosis Gap

According to Society for Women’s Health Research, it takes an average of 3.6 years for patients with fibroids to seek treatment. Just over 30 percent of patients wait more than five years for treatment.

Dr. Marsh heads the reproductive endocrinology and infertility division at UMichigan Health, which ranked No. 48 on the OB/GYN specialty list.

She said that in theory, fibroids are easy to diagnose. The gap in getting treatments, she said, comes from what she called “the four deadly Ds” – delay, dismissal, denial and disrespect. Many patients delay treatment because their physicians dismissed their concerns or symptoms as “normal”. Some patients, in fact, report feeling explicitly disrespected by clinicians because they feel they are not heard or taken seriously.

While Marsh doubts that providers are being malicious, she notes that even doctors and nurses can have unconscious bias when caring for certain groups of people. One of the challenges with diagnosing fibroids, she said, is that providers often are not asking patients the right questions.

They may ask whether a patient’s periods are normal, for example, but fail to make it clear that her heavy bleeding or excessive pain are not typical and might indicate a problem. Doctors, therefore, must dig deeper into what exactly a patient considers her “normal” period or symptoms to better understand the full picture.

“We have to have patients feel comfortable and providers feel comfortable asking those kinds of questions to make sure we are not missing a patient who is having abnormal bleeding from fibroids,” Marsh said. “The reality is, all patients are different and all providers are different and some are better listeners than others, some are better at showing compassion than others, some are better at creating safe spaces than others.”

Increasing Awareness

Despite being a prevalent condition among women, funding for fibroids research remains relatively low.

In 2024, the NIH provided only $17 million in funding for fibroid research, putting it in the bottom 40 of the 330 conditions funded. Yet the direct and indirect costs of fibroids reach up to $34 billion annually, when factoring in the costs of treatment and work lost.

Marsh said, “mortality shouldn’t be the bar” for treating a disease that causes a significant decrease in quality of life and mental health in such a large swath of the population.

“Women deserve better, to be able to live their lives and experience optimal health, given the responsibilities that many women carry in society and in their households,” she said.

Better treatment for fibroids requires more funding for research so that physicians can better understand the pathophysiology of the disease, the challenges with its diagnosis and access to care and to develop new treatments. Marsh said her goal is to prevent fibroids, not just treat them.

In recent years, funding projects have been launched on a national scale. The NIH’s National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, for example, received a $15 million investment for two research centers to address the health disparities in fibroids. And in July, US Congresswoman Shontel Brown of Ohio reintroduced legislation to create a new federal grant program for fibroid detection.

But Marsh said there also needs to be an educational push so that the general population is not only aware of fibroids but is also comfortable talking about the menstrual cycle overall. And not only among women, but also among men.

“If we can talk about erectile dysfunction openly and have commercials about that, we can talk about fibroids,” Marsh said.

Global Perspective

Fibroids affect millions of women around the world, but there is still little known about their cause.

A recent study published with NIH found that globally, the biggest increases in fibroid occurrences from 1990 to 2021 were in India and Brazil. The study posed that ethnogenetic susceptibility and environmental exposure from pollution or endocrine-disrupting chemicals might be contributing factors.

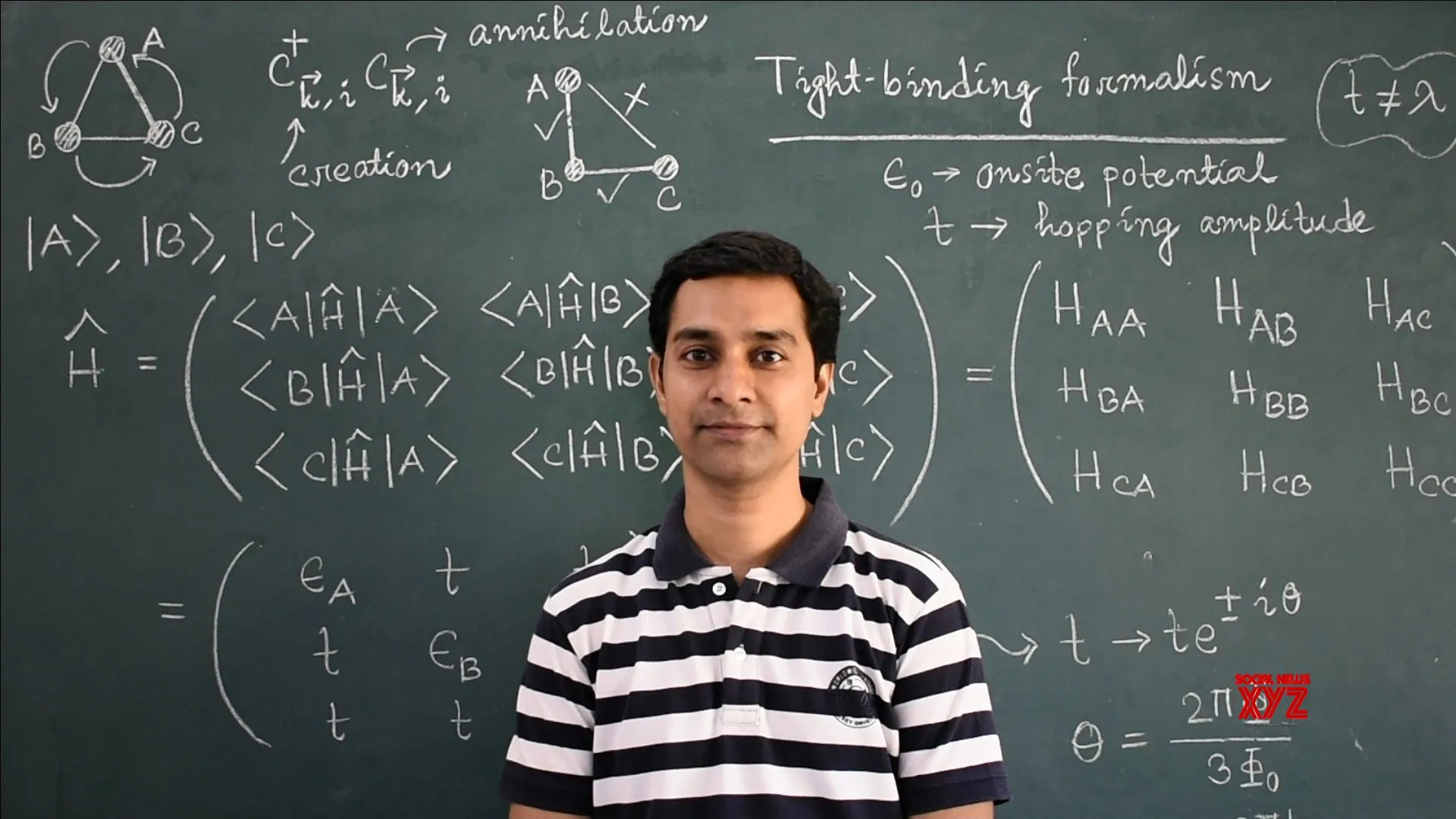

Anshumala Shukla-Kulkarni is the head of minimally invasive gynecology and gynecologic laparoscopic and robotic surgery at Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital in Mumbai, India. The hospital was ranked No. 42 on Newsweek’s OB/GYN specialty list.

“Some [patients] are given oral medications which are not proven to shrink fibroids and is of no value long term,” she told Newsweek. “Educating women on their menstrual health and the risks of bleeding needs to be explained.”

Shukla-Kulkarni said the prevalence of uterine fibroids in women of reproductive age in India ranges from 20 to 77 percent, with higher incidences in older women. Nearly 60 percent in women aged 40-59 have fibroids, studies show.

Several factors contribute to this high prevalence in Indian women, she added, including hormonal imbalances, genetics and family history, the lack of essential nutrients in traditional Indian diets, rising obesity in India and Vitamin D deficiency.

According to the 2022 Brazilian Census, the number of mixed-race Brazilians in on the rise. About 45 percent of people consider themselves mixed race, up nearly 12 percent since 2010, making it the largest racial group in the country today. The white population is about 44 percent, with Brazilians who consider themselves Black at 10 percent.

Dr. Eduardo Motta, an OB/GYN at Brazil’s Hospital Sírio-Libanês said the country’s national health system enables women to receive annual gynecological exams. “Women are used to going to the doctor, and they use it to talk about symptoms,” he told Newsweek in an interview. “We have this system that is very helpful in terms of providing the assistance for everyone. So everyone has access [to] a gynecological exam annually, for free.”

Hospital Sírio-Libanês was ranked No. 30 on the OB/GYN specialty list for the 2026 ranking.

Performing clinical exams regularly allows doctors to diagnose fibroids as soon as possible and also can help them differentiate between fibroids and other conditions like endometriosis and adenomyosis. This is done through simple ultrasounds and other imaging technology.

Sírio-Libanês sees patients from all over the country and the region in South America – including those who typically cannot afford top-tier medical care.

“That’s very important because we can train our doctors to be able to talk and to have empathy to people from all strands of our society, and that makes those doctors more acquainted to people, which brings more humanity to the way we deal with our people,” Hospital Sírio-Libanês OB/GYN Dr. Alexandre Pupo told Newsweek in an interview.

Advances in Treatments

Once women understand the condition better and can recognize the symptoms of fibroids, the next step is finding the right treatment.

The only definitive cure for fibroids is a hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus. But many women don’t want to take such an extreme measure, especially if they are planning to have children. A myomectomy is an option that removes fibroids while keeping the uterus intact, but is not always possible, depending on the fibroids’ size and location.

Dr. Jeffery Ecker, the chair emeritus for the department of OB/GYN at Massachusetts General Hospital, underscored that patients have different symptoms and priorities, like fertility preservation, that will have an impact on the type of treatment they receive.

“Understanding their perspective on things and their goals is really important and being able to do our best to match what they value, to hit their goals,” Ecker told Newsweek. “It’s about having a range of options, including medical therapy and procedures that don’t involve surgery.”

Some medications, for example, manage symptoms and may shrink fibroids. And in some cases, if fibroids are small and symptoms minimal, patients may not seek treatment at all.

Dr. James Adam Greenberg, an OB/GYN at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, told Newsweek there is a big misconception that “fibroids equal hysterectomy – that’s always the last resort.”

Mass General and Brigham and Women’s Hospital were ranked No. 7 and No. 12 respectively on the OB/GYN specialty list.

“That’s the only way to theoretically cure it, but that’s certainly by no means do women need to have hysterectomies in 2025,” Greenberg said. “And the notion that because you have fibroids, you can’t have children, that too is just wrong.”

These treatment options also may require various experts in gynecological subsections like radiologists, oncologists or endocrinologists, for surgery, treatment or diagnostics.

“Our goal has always been to try to get people to the appropriate treatment rather than the appropriate doctor,” Greenberg said. “There [are] so many different ways, if they treat it at all, that there is no one person who’s the master of all of them. I have patients who I’ll send over for Uterine Fibroid Embolization, because after we talk, that’s what we agree is probably the best thing for them and their fibroids and their situation, and they’ll send them over one of my radiology colleagues.”

Looking Ahead

Dr. Greenberg encourages patients to be their own advocates, which includes being open and honest about symptoms, doing research about symptoms and treatments online and knowing when to seek options.

“When you’re with the provider and you’re discussing your fibroids, you should feel comfortable asking them all the things you just went through, and if they’re dismissive, [it’s] time to move on,” he said. “I’m not afraid of my patients Googling things – just the opposite. I prefer them to be informed because I do consider myself well-versed in all the treatments of fibroids and I think that’s what people can expect from their physicians and providers. And if [I] can’t answer you, let me look this up or let me see, let me ask one of my colleagues.”

As technology evolves, Greenberg notes that the simple, cheap and accessible ultrasound is still a great way to diagnose fibroids early.

He said effective diagnosis and treatment is about “embracing the evolution of the technology,” including medications that can shrink fibroids and inhibit growth to prevent surgical intervention in the future.

“I think we’re going to see a huge revolution in the treatment of fibroids going forward,” Greenberg said. “We’re at a place right now in really good reactive treatment and I think you’re going to see that trend towards more proactive treatments. We’ll be diagnosing fibroids earlier and addressing them before they become so problematic.”