“It’s a bad time to be missing data,” said Erica Groshen, an economist at Cornell University who led the Bureau of Labor Statistics during the 2013 shutdown. “We are flying blind right as the economy could be turning.”

That is what distinguishes this shutdown from previous ones, experts say. The last time the jobs report was delayed, by a couple of weeks in October 2013, the economy was on a clear path, with rising gross domestic product and falling unemployment.

This time around, the US economy appears to be at a crossroads. Although growth has been strong so far this year, hiring has slowed significantly in recent months, raising concerns that further cooling could quickly spell trouble for the broader economy. Data from payrolls processor ADP on Thursday showed that employment at private companies dropped by 32,000 in September, the largest decline in more than two years. Another report, from employment firm Challenger Gray & Christmas, showed that companies’ hiring plans are at their lowest level since 2009.

“The question right now is: Why is the labor market weak when everything else is good?” said Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management. “Now not only do we not have data, we don’t have data in a situation where there are some very significant signals coming from the labor market.”

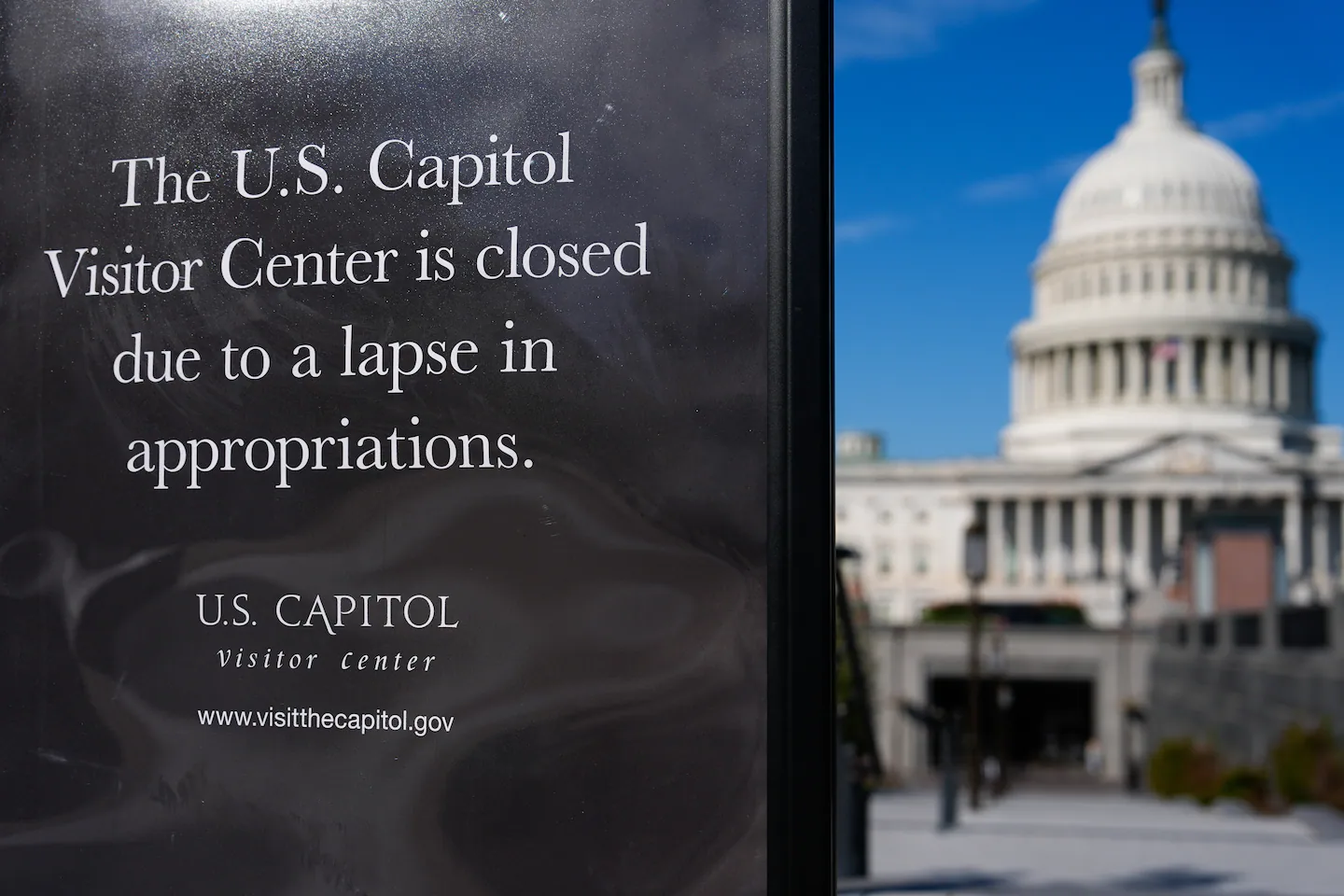

The Labor Department has said it will stop collecting and releasing economic data while the government is closed. “The releases of economic data will likely be delayed if a lapse is prolonged,” the agency said in planning documents. The ongoing shutdown could delay other key economic data too, including inflation reports scheduled for Oct. 15 and 31, and third-quarter GDP figures on Oct. 30.

The lack of data is a particular problem for the Federal Reserve, which will meet later this month to decide whether it should keep cutting interest rates. The central bank is responsible for keeping inflation stable without hurting the job market, and relies heavily on government data to guide its decisions. Without updated figures to gauge the state of the labor market or inflation, the Fed will be in an “extraordinary difficult spot,” Slok said.

The Trump administration has moved quickly to slash funding to Democrat-led states and make other large-scale changes while Congress is divided over funding laws. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent on Thursday told CNBC the shutdown could lead to “a hit to the GDP, a hit to growth and a hit to working America.”

Still, government shutdowns don’t typically leave a discernible mark on the economy. Economists generally estimate that each week of a shutdown results in a 0.2 percentage-point decline in economic growth. The last shutdown, from December 2018 to January 2019, cost the economy about $11 billion, according to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office, though all but $3 billion of that was eventually recouped after the government reopened.

But economists say that could be different this time around. A longer shutdown means a more protracted, and permanent, hit to the economy. The Trump administration has also suggested it may fire thousands of federal employees instead of furloughing them, which could lift the unemployment rate long term.

“The whole question here is duration — if this shutdown lasts a week or two, there isn’t much effect,” said William Beach, who headed the BLS during Trump’s first term and is now a senior fellow at the Economic Policy Innovation Center. “But if it goes for, say, four weeks, then we’re talking about an increase in the unemployment rate. We’re talking about lost productivity. And even more than that, we’re talking about investors becoming spooked about the financial future of the United States.”

The stock market has so far shrugged off the shutdown, with the S&P 500 reaching a record high on Thursday.

But for business owners across the economy, the latest twist out of Washington is adding to ongoing economic uncertainty, making it tougher for them to invest or hire. The US Travel Association, a trade group that represents the tourism industry, said this week that a shutdown would cost $1 billion a week in lost spending.

“These harms ripple far beyond airports and parks, threatening jobs, small businesses, and economic growth in every state,” Geoff Freeman, the group’s president, wrote in a letter to lawmakers.