Copyright Charleston Post and Courier

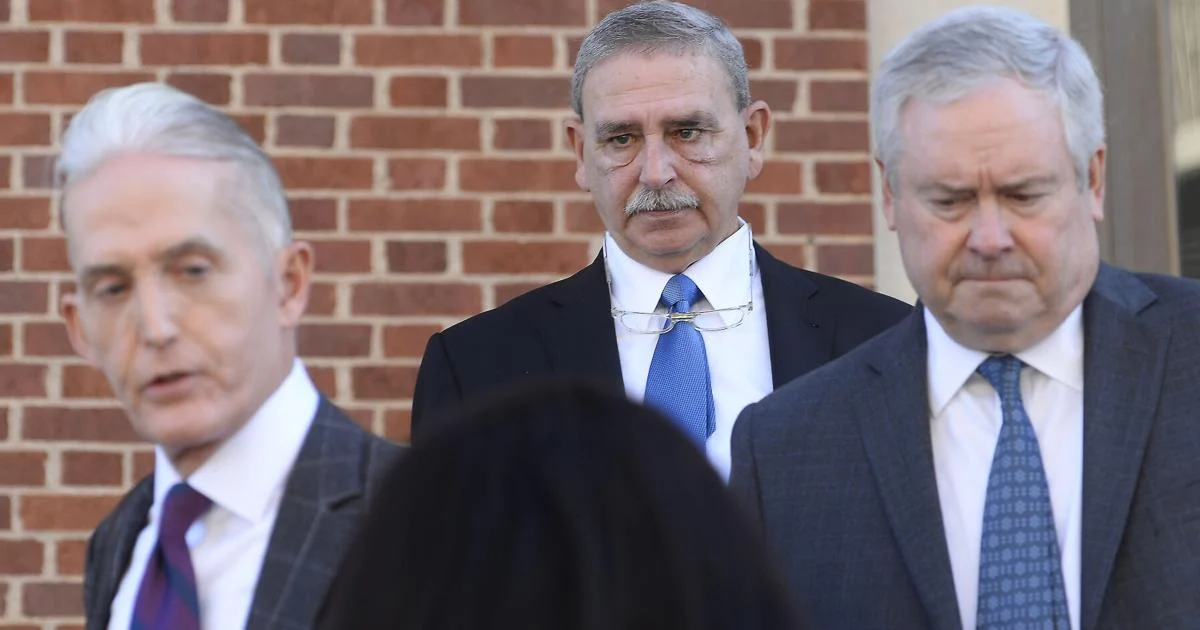

SPARTANBURG — After his May resignation amid an FBI probe into dubious spending practices and drug use that would ultimately lead to a guilty plea, longtime Spartanburg County Sheriff Chuck Wright’s name was stripped from the walls of the office he’d led for two decades. Now, it might be taken off the road that was named for him. It was a surprise in the spring of 2018 when Spartanburg County’s delegation of Statehouse lawmakers approved a resolution to name a stretch of U.S. Highway 29 after the community stalwart, canonizing the 8.5-mile section of road between Interstate 85 and Greer as the "Sheriff Charles L. 'Chuck' Wright Highway." But ahead of its Dec. 4 meeting in Columbia, the same S.C. Department of Transportation Commission board that approved the decision seven years earlier could opt to pull his name from the stretch. This follows Wright’s October guilty plea on three separate federal misconduct charges stemming from his financial management and addiction issues. In a Nov. 4 statement to the media, DOT officials acknowledged that board members would discuss renaming the road at its upcoming commission meeting at the request of Spartanburg County’s delegation in the General Assembly. There’s a longstanding tradition in South Carolina of naming things after people. According to DOT, some 1,945 sites systemwide, ranging from highways and interchanges to bridges and intersections, have been dedicated to some person of importance. Governments have also made it common practice to memorialize public buildings, facilities and even landmarks after the individuals most crucial to their success. “Generally, my preference is to reserve ‘namings’ as memorials to honor the lives and accomplishments of exceptional service, sacrifice or work,” said Beaufort Republican Shannon Erickson, chair of the House Education and Public Works Committee. For the legislators and transportation officials with the authority to name these assets, that list of exceptional people sometimes can include the living. The Leatherman Terminal in Charleston notably was named for the late Senate Finance Committee chairman, Hugh Leatherman, who helped facilitate the arrangement to construct the new terminal while he was still in office. South Carolina’s monumental senator Strom Thurmond had so many things in South Carolina named after him — lecture halls, government buildings, even lakes — that it became something of a punchline in political circles. And congressman Jim Clyburn personally attended the 2003 ribbon-cutting for a Columbia-area pedestrian bridge named in his honor. Just this past year, an aggravating interchange in the Columbia area known as Malfunction Junction was renamed by DOT commissioners after outgoing Department of Transportation chief Christy Hall, even as the project she had championed still was under construction. Lawmakers have fun with road dedications. In the closing days of the 2025 legislative session, Senate Transportation Committee Chairman Larry Grooms, R-Bonneau Beach, cracked a joke that the “road naming store closes Wednesday,” underscoring how commonplace the practice has become. But there is an acknowledged risk inherent in naming infrastructure and monuments for the living or for those who still occupy positions of power — one that gives lawmakers pause no matter how popular a public official might be. “I'm not entirely opposed to naming highways after somebody living,” said Sen. Ed Sutton, a Charleston Democrat who sits on the Senate Transportation Committee. “If there's opportunity to name a road after Joe Riley right now, sign me up. I'll sponsor that. But I do think it's probably more appropriate for people who are either walking out the door or retired as the more appropriate metric there.” There are plenty of examples of highways needing to be renamed. An expressway by the Columbia airport named for former DOT official John Hardee was eventually renamed and later dedicated to congressman Joe Wilson after Hardee’s 2019 arrest for soliciting a prostitute. Prior to that in 2005, state officials moved to remove the name of disgraced former Lt. Gov. Earle Morris from his highway after his conviction on federal fraud charges. Both the General Assembly and the DOT board have the authority to dedicate highways, bridges and other infrastructure. Some have begun to sour on the idea of naming infrastructure after the living, equating it to using taxpayer dollars to commit monuments to the powerful. Former Columbia Mayor Bob Coble has had several places in his honor, including a ballroom, a city plaza and a highway interchange. He told The Post and Courier that while he was a beneficiary of the practice, he believed it had merit as a means of commending lesser-known public servants so that their accomplishments might be recognized while they are still alive. “If you had to wait for someone to pass away, time may have gone by such that their service has been lost to history,” Coble said in an interview.