Copyright Scientific American

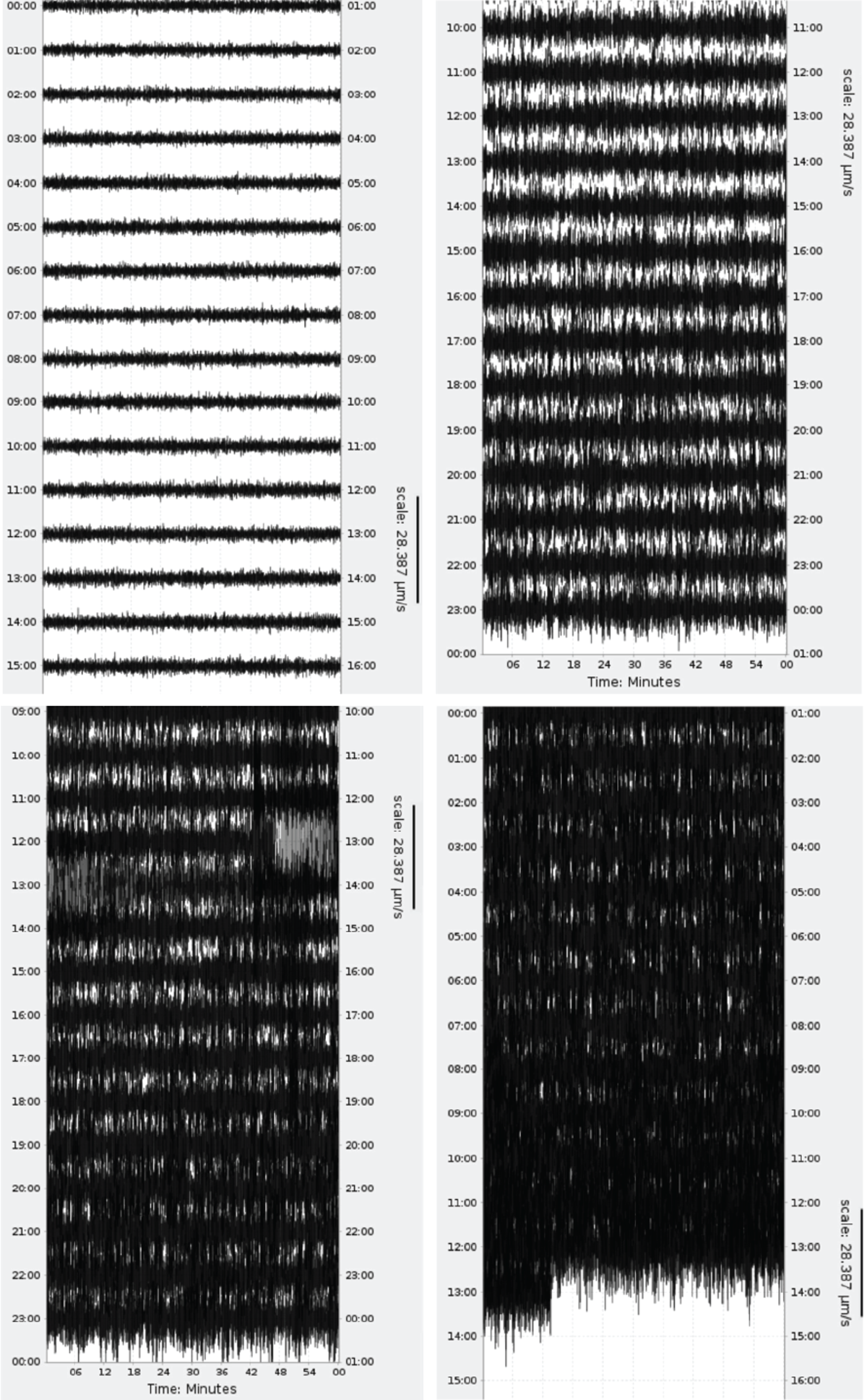

Hurricane Melissa will go down as one of the worst hurricanes ever in the Atlantic Ocean, with the hurricane reaching a strength that only a handful of storms have achieved in recorded history. Melissa was so powerful—with astounding 185-mile-per-hour peak winds—that it literally made the ground tremble hundreds of miles away in Florida, where its march across the ocean was picked up on seismometers, instruments designed to detect earthquakes. Though plenty of intense storms have shown up on these sensors before, the recordings underscore the destructive force of the Melissa, a Category 5 hurricane that devastated parts of Jamaica, Cuba and the Bahamas. They also highlight how a tool that is typically used for geological purposes can improve our understanding of one Earth’s most ferocious weather phenomena—in particular, by opening a window into the hurricanes that raged before satellites and plane reconnaissance was possible. Despite seismic waves being readily associated with fault movements and their tremors, “seismometers aren’t just used for earthquakes,” says seismologist and earthquake geologist Wendy Bohon, whose organizational affiliation can’t currently be given because of the ongoing shutdown of the federal government. “Seismometers detect anything that puts energy into the ground. That could be Taylor Swift concerts; that could be construction; that could be people walking around seismometers.” Landslides, avalanches, asteroid impacts, volcanic eruptions and clandestine nuclear weapons explosions all appear as curious squiggles in the tools’ output because they all generate seismic waves. On supporting science journalism If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today. Hurricanes and typhoons are no exception, and they wobble Earth’s crust in two different ways. The first is “due to the wind vibrating trees, telegraph poles, fenceposts, etcetera, which then couples into the ground as a seismic wave,” says Stephen Hicks, a seismologist at University College London. The second, more major component comes from the storms jostling the ocean itself. “As waves go up and down, they drum on the ocean floor,” Bohon says. Sometimes this percussive action is represented on seismometers by subtle peaks and troughs. Hurricane Melissa ominously registered on Jamaica’s seismometers as eerily obvious serrated teeth in the days leading up to landfall. “It makes your heart drop a little bit because you recognize the ferocity of the storm,” Bohon says. Hurricanes and typhoons are tracked and studied relatively easily in real time: barometers and daring “Hurricane Hunter” pilots record changes in air pressure, oceanic sensors monitor changing temperatures, and satellites can build three-dimensional pictures of these maelstroms. Seismometers, which run continuously and can be found all over the world, can also be used to track the trajectory of the hurricane, says Andreas Fichtner, a seismologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich. Although helpful in the here and now, this is particularly useful for understanding hurricanes in the somewhat more antiquated past—back when aerial surveys and satellite sleuthing weren’t options. “In the presatellite era, we already had a seismic network on the surface of the Earth,” Fichtner says. It’s not anywhere near as dense as it is today, but it’s still sufficient for hurricane researchers hoping to rewind time so they can find out where tropical cyclones used to be born and where the storms previously dissolved away. This multidecadal seismic soundtrack also shows potential in determining the intensities of past hurricanes. Storm-generated seismic waves are effectively recording changes in ocean wave height. That means scientists could calibrate the cacophony of today’s hurricanes with their intensity and then use what’s preserved in old seismic catalogs to see if cyclones have become stronger over time. As sea-surface temperatures have risen dramatically with global warming, climate models have predicted that, over the coming years, hurricanes will get stronger, bringing higher wind speeds, greater rainfall and more vigorous storm surges to bear on anyone in their paths. There are some indications that this effect is already in play. And if, as recent research suggests, seismometers can determine the strength of tropical storms that existed long ago, our understanding of this trend will undoubtedly improve. The fact that seismometers can be used in an unconventional way to study our rapidly changing world is fascinating, Bohon says. But seeing increasingly savage storms such as Melissa appear on these sensors is also “frightening and heartbreaking,” she adds.