Businessweek | The Big Take What Really Happened in the Storm Clouds Over Dubai?

Torrential rain drenched the city in 2024, killing at least four people and raising new questions about the UAE’s cloud seeding program.

Share this article

The storm clouds rolled in again at 3 p.m. Dubai was already drenched from torrents of rain that had started the previous evening, flooding roads and subway stations. Now, on the afternoon of April 16, 2024, another weather front loomed. It appeared almost as a solid object—a gigantic disk, miles across, framed by greenish light like a Hollywood special effect. Social media users compared the scene to an alien spaceship breaking cover.

The downpour arrived moments later. Palm trees buckled in sideways rain, and thunder boomed overhead. By evening, it was clear that the United Arab Emirates was experiencing a once-in-a-generation storm. Dubai International, the world’s second-busiest airport, closed when its runways turned into rivers.

Images began to circulate online of the desert metropolis, famous for its sunny climate and extravagant displays of wealth, swamped by floodwater. “Crypto Bitlord,” a digital currency influencer, recorded himself steering a sports car through murky water, saying, “This Lamborghini is swimming, bro.” The cryptocurrency conference he’d been planning to attend was one of two washed out that day. A golfer posted a clip of someone paddleboarding down the fairway at the sprawling Dubai Sports City complex. The total damage across the UAE was estimated at $3 billion. At least four people were killed.

Afterward, many experts attributed the storm’s violence to climate change. A warmer planet means more moisture in the air, which means more water for rainfall. In the darker corners of the internet, though, there was another explanation: geoengineering, the deliberate manipulation of climate by humans. The term gets used for both imaginary and real activities in the sky. Chemtrails—plane vapor streams supposedly loaded with dangerous chemicals—don’t exist. Cloud seeding—in which particles are introduced into the atmosphere to encourage rain—does.

In fact, more than 50 countries do it. The UAE’s National Center of Meteorology (NCM) has been seeding clouds for years, trying to squeeze out extra water for an arid region with a booming population. “The UAE has proven that even the driest lands can flourish,” a video produced by the agency on its seeding program proclaims.

After the April 16 floods, some on social media were quick to seize on that history, claiming the government was responsible. “Guess this is the result when you overdo it with the cloud seeding,” one anonymous X user wrote. Others blamed a “satanic cabal” of weather manipulators and accused Bill Gates of trying to block out the sun.

Fact-checkers at the BBC, the German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle and other outlets quickly dismissed the idea that cloud seeding had contributed to the Dubai floods. The science behind it has been around since the 1940s, but the evidence that seeding works in practice isn’t rock-solid—it probably does, but it’s frontier territory. Bizarre, unexplained things happen up there, at molecular scale.

In any case, Emirati authorities denied attempting to alter this particular weather system. “We did not use cloud seeding, because [the storm] was already strong,” an NCM spokeswoman said the next day. (Senior officials and spokespeople at the NCM didn’t respond to emails seeking comment for this story. The UAE’s foreign ministry also didn’t reply to messages seeking comment).

Seemingly debunked, the idea that cloud seeding caused the flood appeared to be en route to the tinfoil-lined trash can of history, alongside flat Earth theory. But some doubts remained, even in the scientific community. “The Dubai floods act as a stark warning of the unintended consequences we can unleash when we use such technology to alter the weather,” Johan Jaques, a meteorologist at environmental data company Kisters, told Newsweek on April 18, two days after the rains struck.

A similar cycle of disaster, accusation and denial played out in the US earlier this year, when more than 100 people drowned in Texas over July Fourth weekend. Afterward, conspiracy theorists pointed to a seeding mission that had taken place two days earlier, releasing a small amount of silver iodide in skies 100 miles from the subsequent flooding. The contractor involved got death threats. Republican Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene claimed that an unspecified “they” control the weather and later called for geoengineering to be made a felony.

Although the idea of a political plot to drown Republican voters is manifestly absurd, the reality of cloud seeding is harder to pin down. Even today, meteorologists don’t really know how clouds work, let alone what happens when chemical agents are introduced. It’s not crazy to ask whether recent advances in the technology might have an effect on extreme weather, especially if used carelessly.

What follows is a full account of the 2024 Dubai floods, based on interviews with insiders at the UAE cloud-seeding program, pilots and meteorologists, and on new flight data that challenges the accepted version of events. It’s the story of a catastrophe, weird science, competing narratives and unintended consequences.

Monday, April 15, began calmly. The outer fringes of the storm brought ashen skies. State-owned broadcaster Dubai One warned of thunderstorms and hail in the evening, with the possibility of flooding. “The bad weather is expected to continue through Tuesday.”

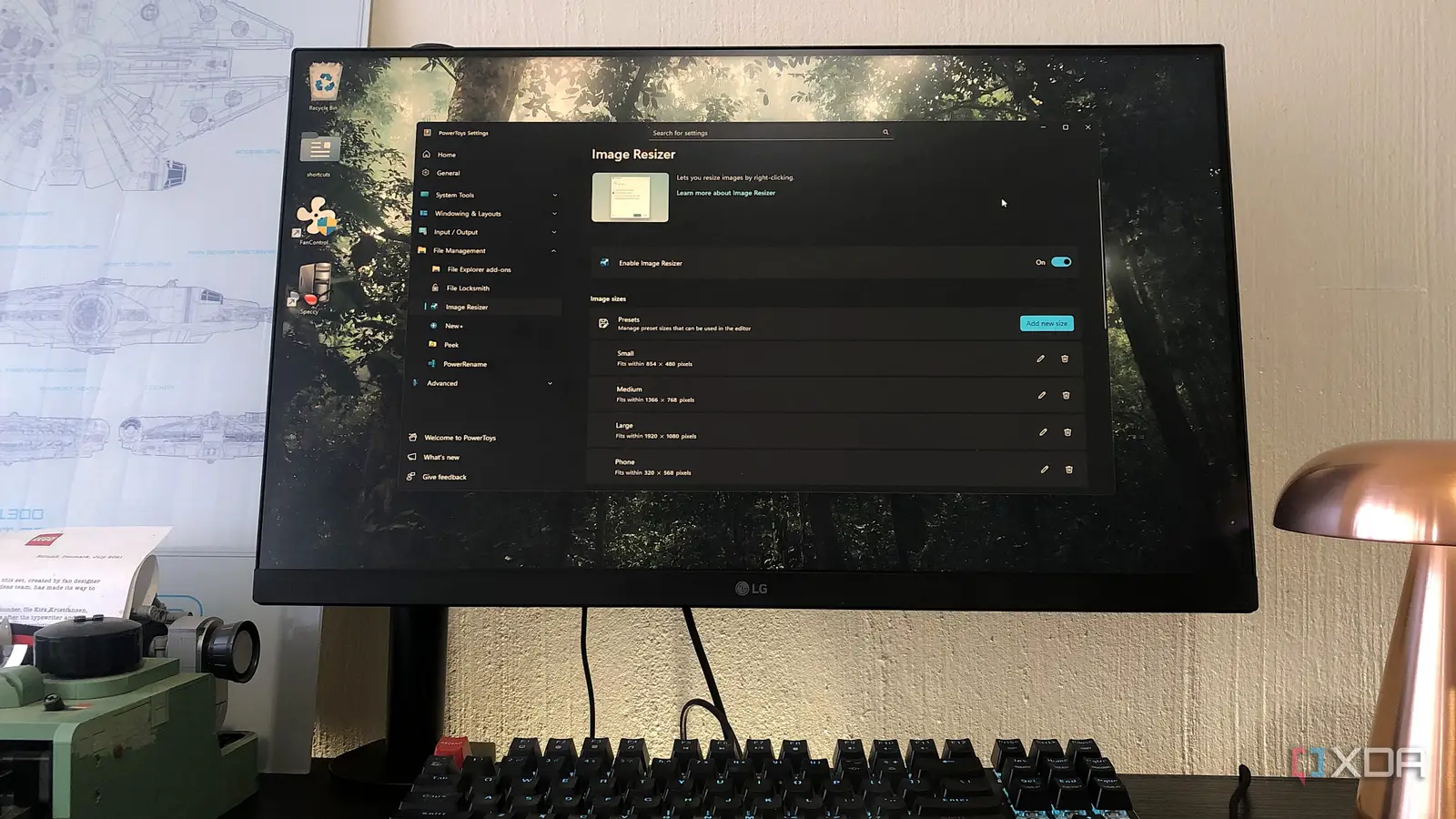

At around 1:40 p.m., radio receivers picked up signals from United Arab Emirates Air Force 836 heading north over Dubai. The plane cruised past Palm Jumeirah, a tree-shaped man-made archipelago whose residents include hedge fund traders, movie stars and Russians fleeing international sanctions. With zero personal taxes, great golf courses and abundant shopping malls, Dubai is a welcoming place for the rich.

UAF836 is a Beechcraft King Air twin-propeller plane. It’s small, agile and tough. The ones used by the UAE’s cloud-seeding program are equipped for a single purpose, former pilots say: delivering seeding agents into the sky. Racks holding dozens of flares lined each wing, each tube containing salt crystals coated with titanium nanoparticles. When burned, the flares release their payload. The crystals are hygroscopic, meaning they absorb water molecules, holding them until they can form a droplet heavy enough to fall to the ground. That’s how cloud seeding works.

UAF836 was the only seeding plane whose flight path was tracked on April 15, but the UAE’s weather agency has at least six similar craft. The planes can work in shifts, lining up to hit a promising cloud in succession like a bomber squadron.

Because of their small size and air force registration, seeding planes don’t always show up on satellite or other public surveillance systems, making them hard for outsiders to monitor. The UAE doesn’t release information about specific missions. Flight tracking company AirNav Systems provided some of the data for this story using multilateration, which involved triangulating UAF836’s position from broadcast signals pinging off nearby ground stations.

The plane bore east and flew inland, passing over the Margham Gas Plant and Field, where metal pipes transport some of the hydrocarbons that have transformed the UAE into one of the world’s richest nations. Dubai’s oasis of luxury is also thirsty, thanks to all the golf courses, fountains and swimming pools—and average rainfall of only around 90 millimeters (3.5 inches) per year. London, by comparison, gets about 600 millimeters.

At around 2 p.m. in Dubai, 20 minutes after UAF836 flew overhead, it began to rain.

Cloud seeding was discovered by accident in the 1940s. A scientist at General Electric Co. left dry ice—solid carbon dioxide—in a freezer chest. In the smoky, supercooled container, ice crystals formed inside a miniature cloud, seeding tiny snowflakes.

There are trace amounts of water in the air all around us. When warm, moist air rises, it cools and turns into the vaporous shapes we know as clouds. But researchers have found that this naturally occurring moisture needs some encouragement to do so, and then to condense into raindrops, hail or snow. Simply put, water molecules prefer to have something to hang on to—a seed.

Several types of particulate matter can do the job. There are natural seeding agents—dust that’s blown into the troposphere, for example, or the miasmic stench of ammonia gas wafting up from penguin poo in Antarctic colonies, above which researchers have observed extra cloud cover. There are unnatural agents, too, such as stratocumulus trails above shipping lanes, caused by engine pollution.

Plain old salt seems to work. In early experiments, pilots tossed it out of plane windows. Dry ice also proved effective outside the laboratory. Dale Roberts, an American who flew missions in the Midwest in 2014, recalls dropping handfuls of it into a storm cloud that was one of three in the area. “By the time I turned around, two minutes later, it was pouring rain out of that cloud and not the other two.”

Since the snowflakes in the GE freezer, scientists have continued to experiment with different seeding techniques, funded by those eager to exploit the weather for their own purposes. The US Army tried cloud seeding to wash away enemy supply lines during the Vietnam War. Today, Indonesia uses it to try to empty clouds away from flooded urban areas. India uses it to combat drought. American ski resorts use it to top up slopes with fresh powder. Before the 2008 Summer Olympics, Beijing had 32,000 people working on a program in which planes and rockets fired shells filled with silver iodide crystals to make approaching clouds rain before they reached the stadium. Whether by luck or design, the opening ceremony was dry.

Even after decades of research, such methods remain controversial within the scientific community, something a fact sheet published by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) acknowledges. An important principle of cloud seeding is that it can’t increase the amount of moisture in the air, creating something from nothing. Clear blue skies will stay clear and blue, no matter how much silver iodide is sprayed. Seeding can only enhance the amount of water that falls out of clouds, like squeezing a sponge.

And its effectiveness is still disputed. Some trials reported enhanced precipitation, but others delivered “inconsistent” results, according to the WMO report. Estimates of the extra rain attributable to seeding range widely, from almost nothing to 45%. Part of the problem is that every cloud and every shower are unique, so it’s hard to know how much would have fallen anyway. Meteorologists have to rely on statistical models or observe experiments in miniature, inside laboratory cloud chambers.

The WMO says it “neither promotes nor discourages the practice of weather modification.” Instead, the agency urges researchers to use sound scientific methods and keep a close eye on the “potential effects on the environment and human health,” both intended and unintended.

Stephen Broccardo, a NASA engineer who worked with the Emiratis 20 years ago, when the UAE’s program began, says weather modification is a global industry, with proponents and detractors, honest scholars and snake-oil salesmen. Of cloud seeding, he says, “nobody on earth understands why it does or doesn’t work.”

UAF836 approached the Hajar mountain range, 60 miles from Dubai, at 2 p.m. on April 15, according to AirNav data. The spine of peaks running up the country’s eastern border is the most productive place to seed clouds, say UAE researchers, because it diverts warm air currents upward, a key element of cloud formation. Nearby dams store fresh water, though their reservoirs often dry out in summer.

The plane flew a couple of tight patterns distinctive to seeding operations. These target a specific area of cloud, strafing the base with hygroscopic agents, which are lifted by warm updrafts into the towering plume where droplets are made. At around 2:30 p.m., the NCM reported heavy downpours, thunder and lightning at a weather station in Hatta, roughly 30 kilometers (about 19 miles) to the south of where the plane had flown.

UAF836 was detected again at around 4:30 p.m., flying loops near Al Dhaid camel racing track at the base of the Hajar range, where dry, flood-prone creeks known as wadis run all the way down to the coast. Throughout the afternoon, the NCM posted on X about “the rains of goodness,” a phrase that in Arabic evokes a blessing—water to help farms flourish and the desert bloom.

What was developing over the UAE is known as a mesoscale convective system, in which lots of individual thunderstorms converge into a single, roiling mass. This one was roughly the size of France. On the night of April 15, it demonstrated its power. Weather radar lit up in luminous shades showing the rain’s density.

At 4 a.m. on April 16, there was a break in the weather when cloud cover moved northeast, away from the UAE toward Iran. But another front was building over the Persian Gulf, west of Dubai. UAF836 was back in the air at 8:45 a.m., passing over Palm Jumeirah before heading south in the direction of Al Maktoum International Airport. (The multilateration data doesn’t show whether the plane ignited its flares.) As the rain pounded down below, visibility in the Abu Hail district of Dubai was reduced to a few feet. Residents of Al Faya, 50 kilometers to the east, told the Khaleej Times that the morning skies turned as dark as night, with continuous thunder and lightning strikes.

Virtually the entire country was now covered by a blob of dense cloud that was dumping its moisture from a great height. Dubai Parks & Resorts, a collection of three theme parks, announced it was closing for the day. Onpassive Metro Station started to fill with water. A glamping resort was inundated, forcing the rescue of four Russian tourists. Authorities asked residents to stay at home and leave their cars on high ground. Undeterred, some members of Dubai’s immigrant community rolled up their trousers and waded through ankle-deep floodwater to get to jobs as cleaners, construction workers or delivery drivers.

Imported manpower has also helped the UAE become a world leader in weather modification technology. Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, revered as the father of the Emirati nation, dreamed of greening the desert and supported cloud seeding until his death in 2004; he recognized that the country’s strength depended on its capacity to secure fresh water. The UAE’s program began in earnest in 2000, when it joined with the US National Center for Atmospheric Research for a research project in the Persian Gulf. NASA offered its expertise a few years later. Many of the first pilots and meteorologists were recruited from South Africa, where the local weather service had been experimenting with hygroscopic salt flares mounted to aircraft.

Flying into thunderclouds is not for the fainthearted. Visibility can drop to near zero. Pilots might have to navigate lightning, ice or hail, and sometimes all three. One aviator who worked with the UAE program in the early days compares the experience to bumping around a hotel room during a blackout, only with the risk of death instead of bruised shins. “It’s thrilling,” he says. (All the former employees and contractors interviewed for this story asked not to be named, citing confidentiality agreements and fear of retaliation.)

Another pilot recalls being spat out of a cloud upside down. Air currents can push a plane up or down several thousand feet in moments. With nothing but driving rain and gray vapor visible through the cockpit window, the only way to tell where you are is the spinning dial on the altimeter and a lurching sensation in your stomach.

Storms in the Persian Gulf are infrequent but powerful. They emerge and disappear quickly, especially in summer, demanding a swift response if they’re to be seeded. After the UAE moved its program in-house starting around 2003, its weather agency stationed a squadron of modified Beechcraft King Airs at Al Ain airport, close to the Hajar mountains, with a rotating crew of pilots on standby, ready to be airborne on 30 minutes’ notice. Over time the process became almost automatic—see cloud; seed cloud. “If you wait to see if it’s seedable, it’s gone,” a former pilot says.

Unusually, given that it added to the risk of accidents, the Emiratis also targeted clouds at night. One evening in 2018, a pilot ignited his flares over the Louvre Abu Dhabi. He could see the venue’s illuminated dome as it prepared for a concert by Dua Lipa. The performance was later canceled because of bad weather. The air crews joked half-seriously about ruining a pop star’s night, according to someone who worked there at the time.

By 2017 the NCM was spraying so much seeding material that academics found a significant increase in microscopic silver iodide particles at 20 air-quality monitoring stations on the ground nationwide. A few years later, the agency began using experimental titanium nanoparticles to coat salt crystals. The combination was said to be hydrophilic (attracting water) as well as hygroscopic (absorbing water), making for a more efficient seed. As of 2024 the NCM was flying as many as 300 missions a year, multiple times a day during the summer storms that yielded the most rain.

The UAE’s demand for water grows every year, making every drop precious. The majority of its supply comes from desalination plants that boil the salt out of seawater, a costly and energy-intensive process. Weather modification looks cheap in comparison. The NCM estimates that a single dollar spent on cloud seeding produces the same volume of water as $25 spent running the plants.

At just after midday on April 16, the storm briefly loosened its grip on Dubai. The Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building at a half-mile in height, speared defiantly through a thin layer of cloud. But the punishment resumed at 3 p.m. with the appearance of the strangely shaped front that social media users compared to a spaceship.

It was probably what meteorologists call an arcus, a ring formation caused by cold air plummeting down from the top of an anvil-shaped storm cloud, then curling back upward from the base. There was nothing unnatural about the green or yellow tinge—just a trick of the light as the sun’s rays refracted through very wet air—but it did speak to the explosive forces at work. The following deluge was like nothing even lifelong residents had seen before.

Once a cloud droplet grows to 10 to 20 microns (0.01 to 0.02 millimeters), it stops rising and starts to fall. As it descends, it pinballs against tens of thousands of other droplets in a chain reaction that, in taller clouds, can unleash a staggering amount of liquid. The average thunderstorm contains 1 million metric tons of water, enough to fill 400 Olympic swimming pools.

Floodwater in parts of Dubai rose to knee-deep, then waist-deep. Traffic stacked up bumper-to-bumper for 2 kilometers along Sheikh Zayed Road, the city’s main artery.

At around 4:45 p.m., a Bloomberg News reporter spoke to Ahmed Habib, a meteorologist at the NCM, for a story about the floods. The center had been flying seeding missions all that day and on Monday, too, he said. He counted seven operations during the period—meaning UAF836 wasn’t the only plane in the air. Any convective cloud should be targeted, he said. (The NCM would later deny this accounting of events.)

As afternoon turned into evening, the NCM issued its first red warning, indicating the most severe hazard. Flights from Dubai International were delayed, diverted or canceled. At 8 p.m., mosques around the city broadcast the call to prayer, along with a special message asking worshippers to stay indoors.

It’s unclear when on April 16 people started dying. The only information the police released said that a male citizen in his 70s had died when his vehicle was swept away in the emirate of Ras Al Khaimah. Philippine media reported that two immigrant workers, Jennie Gambao and Marjorie Ancheta, suffocated after their shuttle bus was submerged. And a third Filipino, Dante Casipong, a 47-year-old airport technician, was killed when his car fell into a sinkhole. He left behind a wife and three children.

Human intervention in the weather has always attracted suspicion. Centuries ago, attempts at storm-raising were considered sorcery. King James VI had dozens of suspected witches arrested and tortured in Scotland in the late 1500s after a tempest battered his ship in the North Sea.

Cloud seeding itself has been linked to disaster, fairly or not, pretty much since it was discovered. In the summer of 1952, most of the southwestern English village of Lynmouth was swept into the sea by a flash flood, killing 34 people. Villagers suspected the military had been conducting experiments on the clouds, which the authorities denied. Decades later the BBC uncovered a lost interview with an academic who remembered throwing salt from a glider in the days before the flood, part of a military-backed testing program called Project Cumulus. (The UK Ministry of Defence said in a statement to Bloomberg Businessweek that its experiments didn’t yield significant rainfall and that bad weather had caused the floods.)

In February 1978, a creek in Big Tujunga Canyon, California, burst its banks, killing 11 and causing $43 million in damage. Afterward, it emerged that Los Angeles County had seeded the day before the storm. The resulting outcry led to dozens of lawsuits (all unsuccessful) and the cancellation of the area’s seeding program. In South Africa, cloud-seeding pilots were shot at by farmers as recently as the 1990s. And after the Texas floods this year, Florida’s attorney general sent letters to his state’s airports warning of third-degree felony charges for anyone attempting to use chemicals to alter the climate.

The UAE has seen an increase in flooding during the cloud-seeding era. The causes are likely numerous, encompassing climate change and urbanization, which replaces naturally absorbent landscapes with flood-prone concrete ones. Although the UAE’s weather agency has always denied causing storms, it has admitted to seeding them. It has also acknowledged following extreme rains that this might have meant more water on the ground. After a woman was killed during a three-day deluge in January 2020, a spokeswoman noted that the NCM doesn’t “produce” precipitation but does “help the cloud to increase the amount of rainfall.” And after heavy rains in January 2022, the NCM told Agence France-Presse that cloud seeding may have exacerbated the impact. In each case, the center was keen to make clear that it would have rained anyway.

No one knows for sure exactly how cloud seeding affects such powerful storms. Some scientists insist that when condensation is already being turned into rain so efficiently, the impact can only be minimal. “Like a breeze stopping an intercity train going at full tilt,” Richard Washington, a climate science professor at the University of Oxford, wrote in a blog for the news network the Conversation a few days after the storm. On the other hand, scientists with the US National Center for Atmospheric Research, found during a three-year study in Mexico that the largest quarter of storm clouds produced 45% more rain in the half-hour after being targeted than unseeded clouds, according to an article published in 2000 in Science magazine.

The Mexico experiment and other studies have reported that seeded storms seem to last longer. But the turbulence and infinite variety of thunderclouds make it nearly impossible to single out the effect of hygroscopic agents, at least to a scientific standard of proof. It’s hard to separate human influence from natural chaos. Seeding could lead to more rain; it could also lead to less, if it spurs the formation of ice crystals that don’t fall, according to Alan Robock, a professor of climate science at Rutgers University. It could also do nothing at all. “You can’t rule any of those out,” Robock says.

Absent decisive data, some scientists have urged a cautious approach. A 2022 study by academics at the Dubai campus of Heriot-Watt University specifically linked cloud seeding to an increased risk of urban floods, alongside other factors. “Although cloud-seeding increases precipitations and increases groundwater recharge,” the authors wrote, “it has also impacted the performance of drainage networks and urban flooding.” A later review of the academic literature by the same researchers called the possibility of a connection between cloud seeding and extreme rainfall “worrisome.”

The American Geophysical Union has published ethical guidelines for climate intervention research that recommend proper risk assessment to reduce harmful side effects, transparency and “trigger mechanisms that pause or terminate the experiment” if things go wrong.

UAF836 was recorded in the air a final time at 10:30 p.m. on April 16, flying just north of its base at Al Ain airport. A nearby weather station had just logged an astonishing 255 millimeters of rain in the previous 24 hours—almost triple what Dubai gets during an average year. Even though it was the heaviest downpour since records began, the news wasn’t all bad. The storm had the effect of “strengthening the country’s groundwater reserves,” according to the Emirates News Agency, or WAM, the official state news outlet.

Dubai’s inhabitants awoke the following morning to clear skies and a surreal aquatic scene. Several highways were underwater, dotted with submerged cars. A few hardy souls used canoes to check on friends and neighbors. Those forced to sleep overnight in airports or shopping malls began to contemplate how to get home.

That morning, when Bloomberg News contacted the NCM for an update, a spokesman said Habib had been misinformed: Seeding had taken place, but only on the 14th and 15th, before the storm hit full-force. The NCM added a statement saying it hadn’t conducted any seeding operations “during this event” and doesn’t fly missions during extreme weather. (Habib and the spokesman didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.)

Then the NCM’s story changed yet again, this time in a statement to Dubai’s National newspaper. Planes were in the air in the days running up to the storm but had only taken samples, not ignited flares, the NCM said, adding that “we take the safety of our people, pilots and aircraft very seriously.”

For some in the small community of pilots around the UAE cloud-seeding program, these denials didn’t make sense. For one thing, Beechcraft King Airs, like UAF836, aren’t fitted with the specialized equipment required to take cloud samples. All the plane can really pull in is what a former NCM airman calls “Mark 1 eyeball data”—basically, what the pilot senses. “It was purely a cloud-seeding machine,” another former NCM airman says.

Nor did the concern for the safety of the pilots and aircraft ring true for all those who’ve flown for the program. Two former pilots say they were told their jobs would be under threat if they refused to fly in what they’d judged to be unsafe conditions. About a decade ago, one of the pilots says, air crews got in a dispute with NCM management over the use of Bulgarian-made flares that had a habit of exploding when ignited. The NCM relented only after one of the flares blew up midflight and punched a hole in an aircraft wing. When a pilot complained about safety in 2019, he was rebuffed and told, “It’s coming from the sheikh.”

Pilots say they were asked to deliver seeding material both in cloudless skies and in conditions so rainy they could see cars struggling on flooded roads below. “It became this weird box-ticking exercise,” one of the pilots says. The NCM seemed less focused on results and more interested in running up mission numbers to put in its daily reports.

Another aviator recalled raising the alarm after seeing reports of flooding following a cloud-seeding mission. When he told NCM managers they needed a stop button to reduce risk, he was ignored, he says. This pilot was no longer working for the NCM in April 2024 but says he was in contact with former colleagues who were. “My friends were up in that, saying they would get fired if they didn’t fly,” he says. “I don’t know what upsets me more, the lying or the incompetent lying.”

In the aftermath of the floods, Dubai’s state-affiliated newspapers reflected the official account. The global media tended to, as well. A few articles relied on scientists who were either paid directly by the NCM or who’d benefited from Emirati funding. BBC fact-checkers quoted Diana Francis, an atmospheric scientist whose lab at state-funded Khalifa University works in partnership with the NCM, as saying that cloud seeding isn’t used on “such strong systems of regional scale.” (Francis didn’t respond to an email seeking comment.)

The same article quoted two meteorology professors at the University of Reading in the UK whose department had received at least $1.5 million in funding from the UAE to research cloud seeding. The university distributed a press release with the headline “Cloud seeding did not cause Dubai floods” that quoted the professors, without the relationship and funding being mentioned.

The professors, Maarten Ambaum and Giles Harrison, say they aren’t involved in the operational side of the NCM’s weather modification program and didn’t have firsthand knowledge of when missions were flown. They stand by their assessment, though, which they say was based on the principles of cloud physics. In effect, such powerful storms turn condensation into rainfall so efficiently that seeding them is pointless.

Debate about the effectiveness of cloud seeding is unlikely to be settled anytime soon, but it’s hard to imagine, based on the UAE’s own figures, that its seeding runs had no impact at all. In media reports and published studies, officials have cited rainfall increases of anywhere from 5% to 35%. And, as hydrological modeling experts point out, once drainage systems are overwhelmed, the effect of any extra rain at all is magnified. “If the cloud seeding added rainfall to exceed design capacity, then flooding would ensue,” Thomas Kjeldsen, an associate professor in water engineering at the University of Bath in the UK, wrote in an email. “If 10% or 20% is enough, nobody can say, as it depends how much rainfall there would have been in the first instance,” he wrote. “But 10% of a lot is … a lot.”

Two days after Crypto Bitlord’s Lamborghini went swimming, life in Dubai was returning to normal. The digital currency conferences got underway. Attendees drank coffee sprinkled with gold leaf and petted llamas to a soundtrack of thumping techno. Luca Netz, chief executive officer of nonfungible token company Pudgy Penguins, was philosophical about the disruption, telling Bloomberg News “we’ve been through worse.”

This January, cloud scientists from all over the world gathered at a luxury hotel in Abu Dhabi for the International Rain Enhancement Forum, the NCM’s flagship conference. The event fused TED Talk-style oratory—speakers used terms such as “value creation” and “nodes of intelligence”—with militaristic nationalism.

The NCM has a grant program that works like a venture capital arm, investing millions of dollars in promising research projects run by some 1,800 academics worldwide. “Impossible is the beginning,” someone declared. Meanwhile, a UAE flag fluttered on a giant screen and air force officers received medals for their service in making it rain.

There was little mention of what had happened scarcely nine months earlier. Dissenting opinions on official positions aren’t embraced in the UAE. “Virtually nobody in the country speaks out on political and other sensitive issues,” according to Freedom House, a pro-democracy nonprofit. Among the few direct statements about the flooding came from Chaouki Kasmi, chief innovation officer at the Technology Innovation Institute in Abu Dhabi, who declared that “unusual atmospheric conditions,” not cloud seeding, caused the April floods. “Top scientists have proved it,” he said.

“Water is politics,” said Loïc Fauchon, president of the World Water Council, when he took the stage. No one could challenge that assessment, at least. Several of the UAE’s regional neighbors, notably Saudi Arabia and Oman, have cloud-seeding programs that are, theoretically at least, competing for the same air-bound moisture. It’s not hard to see the appeal of controlling the supply of potable water. Twenty years ago, a South African contractor met one of the Emirati leaders backing the nascent seeding operation. “The next world war will be about water,” the contractor remembers him telling her.

Weather modification could be a weapon or a savior. Seeding clouds with seawater on a massive scale, a technique called “brightening,” could halt global warming by reflecting solar rays back into space, said one presenter at the Rain Enhancement Forum. Scientists there also described firing lasers at clouds and using acoustic waves blasted upward from giant speakers to try to shake moisture from the sky. Roelof Burger, a climatology professor at North-West University in South Africa, warned that, as researchers push the field in new directions, seeding technology has the potential to be “dangerous in the wrong hands.”

Whatever the form, geoengineering is likely to become increasingly important as the planet heats up, threatening water supply in some countries, increasing it in others. Or it could all be a tech-utopian fantasy, doomed to fall short against elemental forces that we can barely comprehend, let alone control. The answer depends on who you ask.

Outside, it was another perfect day in Abu Dhabi. A few solitary puffs of cloud drifted overhead. Wisps of vapor, they were barely there at all, certainly not worth dispatching planes for. Soon they disappeared, leaving the desert sun blazing down unimpeded from a clear-blue sky. —With Neil Jerome Morales and Jeremy Cf Lin