Copyright The Boston Globe

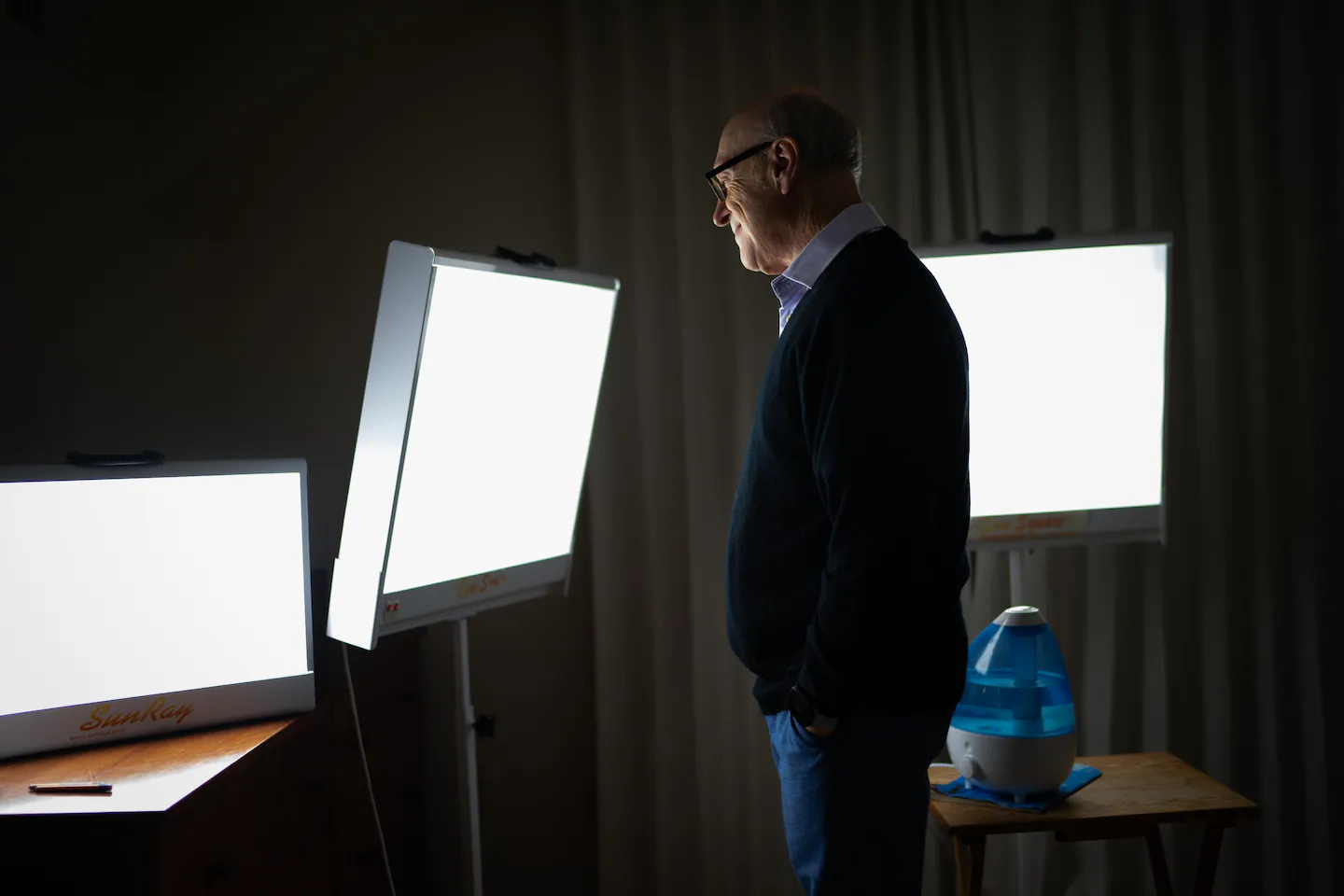

Rosenthal would know: He, along with his colleagues, first described and named the condition in 1984. And he’s had decades of firsthand experience with SAD. Rosenthal remembers traveling from South Africa to the United States in 1976 for his medical training and how much he struggled in those first three years of residency in New York. South Africa, famous for its sunshine, generally has many hours of bright light each day, even in winter. New York City? Not so much. Leaving work at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, the wind and darkness of winter over the Hudson River hit him hard, especially following the end of daylight saving time in November. After he moved to the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland, to study biological rhythms and mood, he started hearing about other people who had similar symptoms as he did. These other cases, combined with his research and lived experience, led Rosenthal to theorize that there was a connection between light and why some people like him had diminished mood in winter. The Washington Post played a role in helping Rosenthal and his colleagues gather even more evidence and data. A 1981 article about Rosenthal’s early work garnered over 3,000 letters from readers around the country about their own experiences. The researchers sent these readers questionnaires about how they felt as the days turned short and dark, and they gave similar answers: “I get tired,” “I eat more,” “I sleep more,” “I crave sweets and starches,” “I feel down.” “Prior to that, there was no sense that there was this entity and that this entity could have a special kind of treatment that might be useful for it,” Rosenthal said. Since then, Rosenthal, now 75, has seen over 1,000 patients with SAD through multiple winters. At first, Rosenthal did not divulge that he also had SAD. But then he thought of the courage of all the subjects in his studies. “They’ve offered their time, their work, their energy to help us characterize and understand this,” he said. “There’s no shame in it, you know, it’s a biological thing.” Researchers believe that wintertime SAD is caused by reduced daylight, which can desynchronize our internal circadian rhythm from the natural light cycles outside. At the same time, light is invigorating and mood-lifting; specialized photoreceptors in our retina connect directly to mood-related areas of the brain. People also have seasonal variations in the mood-related neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine, research shows. (Summer seasonal affective disorder is less well-known and thought to be triggered by the heat, humidity and pollen.) To fight the dark, the answer is to provide more light where it is missing. The standard treatment for SAD is bright-light therapy with a light box that delivers at least 10,000 lux of light. (Run-of-the-mill indoor lights are typically less than 1,000 lux, while direct sunlight can go up to about 100,000 lux.) Research shows that light therapy is effective at improving mood and reducing symptoms of SAD in about 64 percent of patients, according to a 2015 study. For his part, Rosenthal has supplemental light in almost every room of his house. In the bedroom, he has a selection of lights that can be gradually illuminated, including three large light boxes that can be turned on sequentially to help him greet the day. The lights are an integral part of other habits that he’s adopted. (In total, he has 13 light-therapy devices of different shapes and sizes in his home.) “When I wake up in the morning, oftentimes the first thing I’ll do is I’ll draw the curtains and I’ll feel that first morning light. And it’s a great time for mindfulness. It’s a good time to say, wow, look at this: Here is the light. I’m thankful. I’m present. I’m here,” said Rosenthal, who helped develop light therapy as a SAD treatment. In his exercise room, where Rosenthal lifts weights, does push-ups and stretches, as well as yoga once a week, he has set up three light boxes so that light can reach him regardless of where he is in his exercise routine. (Exercise is also a well-established way to help reduce the symptoms of depression.) He also meditates twice daily and takes regular walks outdoors, including weekly with his psychiatrist son, to take advantage of the sun’s natural light. “These are very vital, important things to keep all aspects of your mind and body alive,” Rosenthal said. It is important to keep an eye open to how you are feeling this time of year, said Rosenthal, whose most recent book is “Defeating SAD: A Guide to Health and Happiness Through All Seasons.” Has it changed since the month before? How were you this time last year? While SAD symptoms tend to peak in January and February, the onset can vary from person to person. Think of SAD as a possibility, if “you’re just struggling like I did those first three years of my residency,” Rosenthal said. “We put on a happy face. We do our best. We push ourselves. We drink a little more coffee. But ‘fine’ means really feeling wonderful. And I want people to feel wonderful. Why shouldn’t we? It’s an amazing thing, this world we live in.” Fall is the best time to prepare, especially if you’ve had issues during winter in the past. Getting a light box may help those who are struggling. After all, light therapy also can help in nonseasonal depression, Rosenthal said. A 2024 meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials found that bright-light therapy is effective as an added treatment for nonseasonal depression and may speed up response to the treatment. Rosenthal says people don’t need to go as far with lights as he does and recommends speaking with your doctor or mental health professional about your particular needs. Doctors generally recommend you sit in front of the lights for at least 30 minutes a day. Light therapy is most typically prescribed in the early morning, which studies show is the most effective time to shift circadian rhythms to align with the environment. However, using light therapy near the end of the day also can be effective so that you don’t feel the “suddenness” of the winter darkness, Rosenthal said. “Be cognizant of replacing what’s missing.” Besides sitting indoors with light boxes, Rosenthal recommends “walking outside, enjoying the seasons. They’re beautiful, but you can only enjoy them when you’ve treated your biology.” Antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapy are very effective for “many different kinds of depression, and SAD is no exception,” Rosenthal said. “I say whatever works. You know, sometimes the light is sufficient. Sometimes it needs a little help with the medicines, but you know, be in tune with yourself. Be in tune yourself in the seasons. Then you’ll be able to enjoy all the seasons,” Rosenthal said. Even if you are losing just 10 percent of your usual functioning this season - feeling just a bit more tired, more down or more lethargic - it’s something that needs to be identified and addressed. “It is consequential to be at one’s peak, not just performance, but peak experience and enjoyment of life,” Rosenthal said.