Copyright scotsman

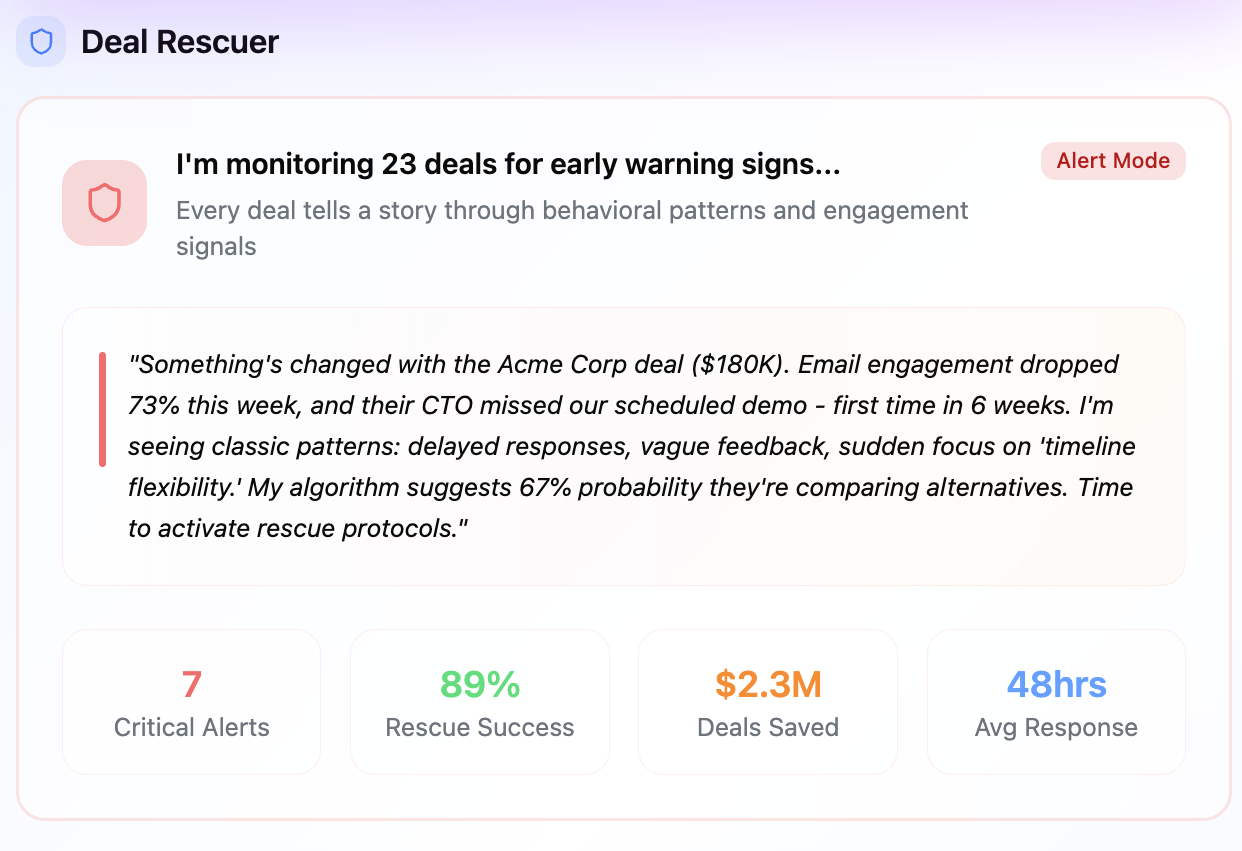

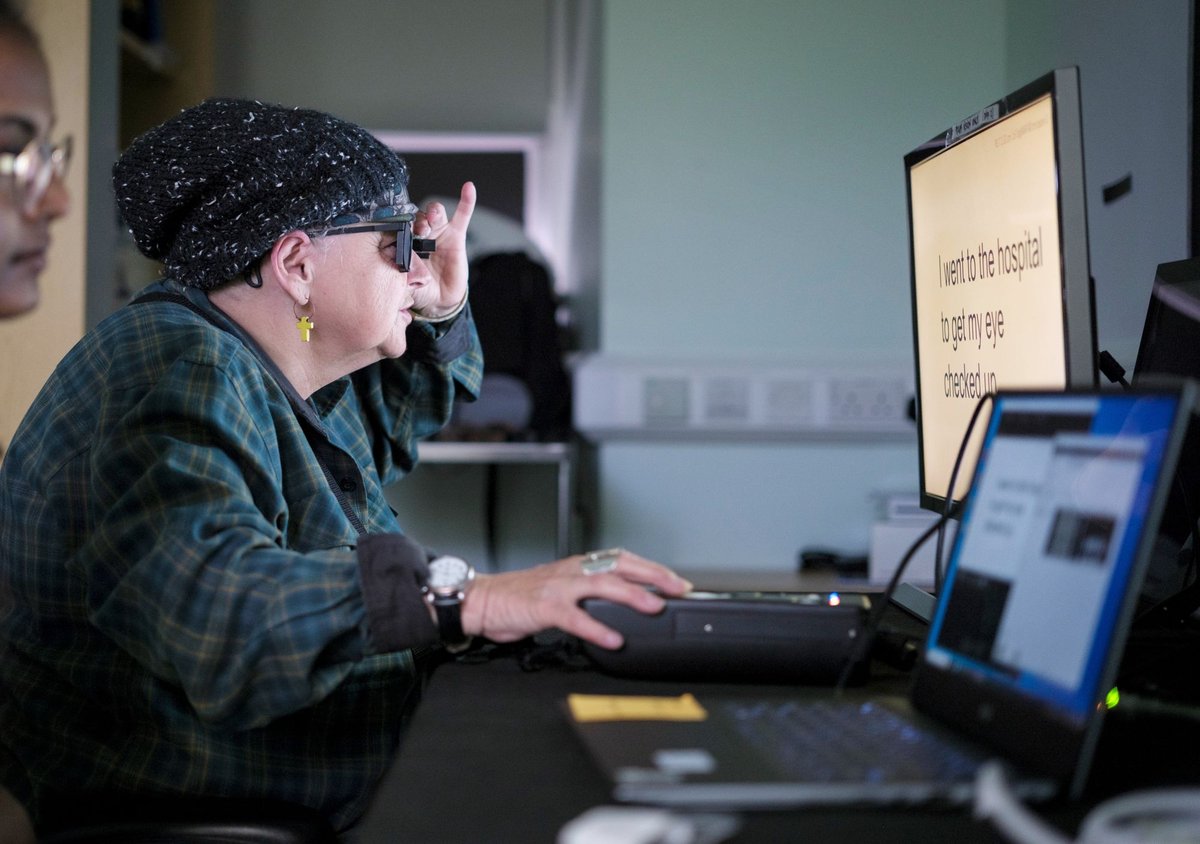

A Scottish surgeon who helped people with incurable sight loss to see again after fitting them with pioneering electronic eye implants has hailed the breakthrough as the dawn of a “new era” in tackling blindness. Mahi Muqit, a consultant ophthalmic surgeon from Glasgow who led the UK trial of the so-called “prosthetic vision” device, described the results as “life changing,” with some of his patients now reading and writing, or doing crossword puzzles. The technology offers hope to hundreds of thousands of people across the UK - and millions more around the world - who have an advanced form of dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) called geographic atrophy (GA), a common but untreatable condition which impacts cells in a small area of the retina at the back of the eye. However, the new implant, a photovoltaic microchip with the thickness of a human hair, allows patients to see letters, numbers and words through an eye that was previously blind. Mr Muqit, who qualified as a doctor from the University of Glasgow in 1998 before later beginning his specialist ophthalmology training at the renowned Tennent Institute in the city’s Gartnavel General Hospital, described the technology as a “paradigm shift,” and expressed hope that it would one day be available on the NHS. The world-first trial of the tiny Prima device involved 38 patients across 17 sites in five countries, including the UK, France, Italy and the Netherlands. Those involved in the study had lost the central sight in the eye being tested and had only limited peripheral vision remaining. The procedures in the UK arm of the trials took place at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, where surgeons removed the clear, jelly-like substance from inside the eye in what is known as a vitrectomy. A trapdoor under the centre of the retina was then created, where the 2mm by 2mm chip was posted.To see words and write, patients wear augmented reality glasses, which contain a video camera. This is connected to a small computer attached to their waistband, which includes a zoom feature to make the text bigger. The video camera in the glasses projects scenes as an infra-red beam across the chip, which activates the device. Artificial intelligence in the waistband computer then processes the information, which is converted into an electrical signal.This signal passes through the cells in the retina and optical nerve into the brain, where it is interpreted as vision. Mr Muqit, senior vitreoretinal consultant at Moorfields and the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, said: “I have all these patients who are blind, and when you see them, they want to know is there anything that can restore vision. And the answer has always been no. “We’ve got some patients who are now reading books, their quality of life is much higher. Some of them are writing, doing crossword puzzles, things they enjoy. “You have to realise you’ve got blind patients who are depressed and socially isolated, who are now able to start to function and pick up things that they used to enjoy.” He added: “In the history of artificial vision, this represents a new era. Blind patients are actually able to have meaningful central vision restoration, which has never been done before.” Mr Muqit, 50, is among the co-authors of a new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine detailing the findings. It suggests that 84 per cent of patients on the trial were able to read letters, numbers and words while using Prima, and on average, could read five lines on a vision chart. Before the device was fitted, some of the patients could not even see the chart. While the chip is permanent, patients can wear the glasses for as long or as often as they like. Mr Muqit explained: “There’s no pain, there’s no safety issues, inside or outside, because the device only switches on once you put the glasses on. There’s absolutely no time limit, they can use it every day, as long as they like.” Subscribe today to the Scotsman’s daily newsletter Sheila Irvine, one of the patients who took part in the trial at Moorfields, said she is now able to read her prescriptions, do crosswords, and study the list ingredients on tins. She said that prior to the operation, her vision “was like having two black discs” in her eyes, “with the outside distorted.” “There was no pain during the operation, but you’re still aware of what’s happening,” Ms Irvine added. “It’s a new way of looking through your eyes, and it was dead exciting when I began seeing a letter. It’s not simple learning to read again, but the more hours I put in, the more I pick up.” The developers of Prima, US-based medtech company Science Corporation, are now working to secure regulatory approval for the device. The implant is not yet licensed so is not available outside of clinical trials, and it is unclear how much it may eventually cost. Mr Muqit said he hoped others would be able to benefit from the technology in the future, adding: “I would have to say, it’s a whole paradigm shift. You talk to surgeons in the UK that I’m colleagues with, and they’re all very excited by this particular technology. You know that this technology will be scalable.” Dr Peter Bloomfield, director of research at the Macular Society, described the interface between biological and digital systems as having “great potential.” He said: “These are encouraging results which indicate an improved quality of life to patients living with dry AMD, particularly GA. Where there is currently no treatment option, this is fantastic news. “Artificial vision may offer a lot of hope to many, particularly after previous disappointments in the world of dry AMD treatment.”