Copyright Slate

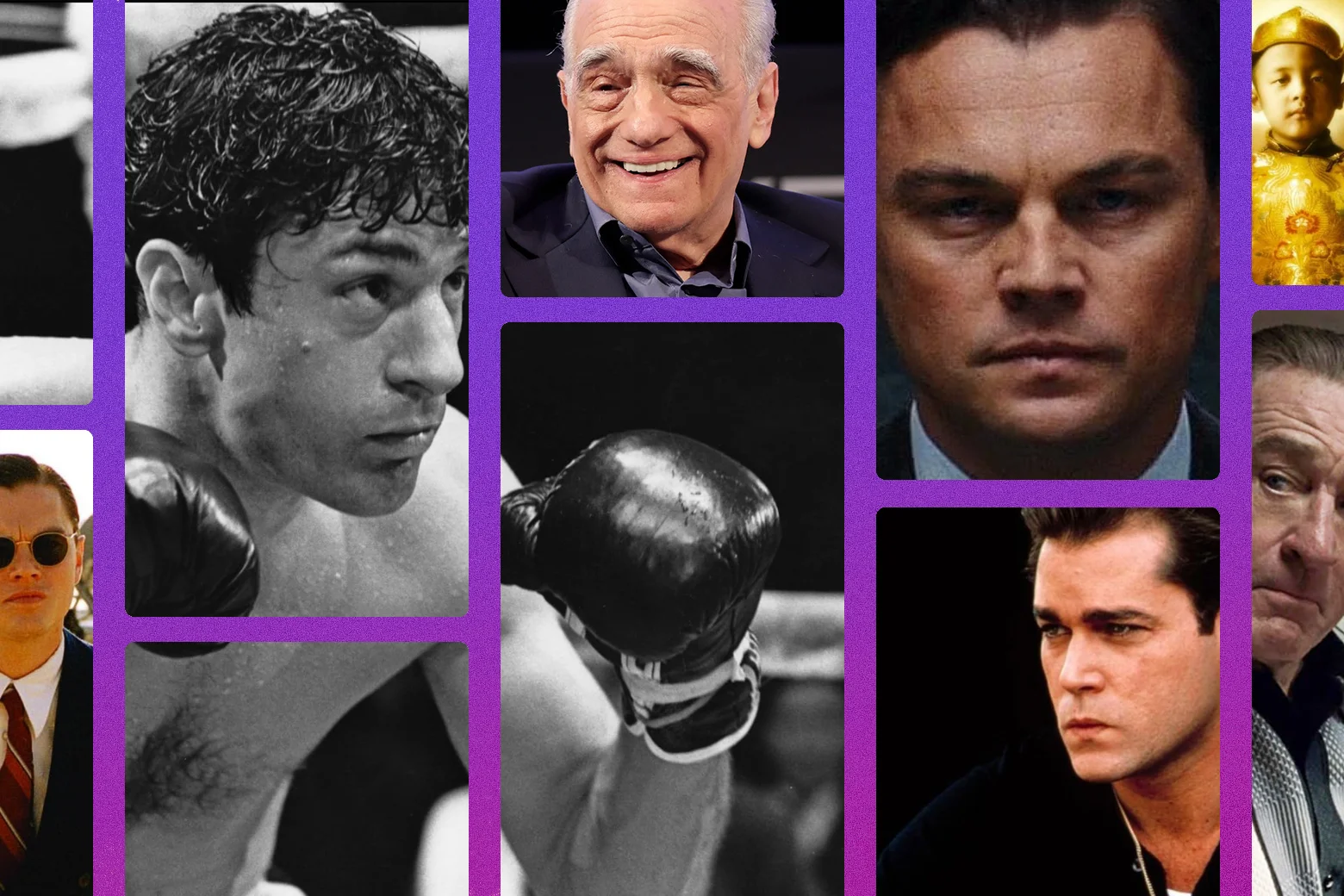

This article is part of Portrait Mode, a Slate pop-up series about biopics. Martin Scorsese’s 1997 film Kundun is famous mostly for being unknown, or at least unseen. Kundun is the ne plus ultra of footnotes in the career of one of the most esteemed filmmakers in history, who chose it as his follow-up to 1995’s big-budget gangster epic Casino. Universal was originally set to produce the film, which is about the early life of the Dalai Lama up until his 1959 exile from Tibet, but balked when it became clear its subject matter and politics would offend the Chinese government. Disney then picked it up, but ultimately opted to bury its release out of similar concerns. Kundun premiered on Christmas Day in 1997 on only two(!) screens in the United States, and ultimately grossed less than $6 million total on a nearly $30 million budget. In 1998, Disney CEO Michael Eisner apologized to Chinese officials for releasing the film, saying: “The bad news is that the film was made; the good news is that nobody watched it.” In the decades since, the latter part of that statement has remained largely true: Kundun’s biggest pop-cultural footprint is still probably as a Sopranos punch line that plays off both its obscurity and its seeming incongruity in the career of the guy who made Taxi Driver and Goodfellas. Kundun is, in fact, a pretty good movie. It’s not top-tier (or even second-tier) Scorsese, but as minor works by great filmmakers go, it’s certainly not some fiasco on the level of 1941 or Bonfire of the Vanities. (In Rebecca Miller’s terrific new five-part, career-spanning documentary Mr. Scorsese, Kundun receives, by my count, about two minutes’ worth of attention, which is probably appropriate.) Kundun is also not as out of step with Scorsese’s overall filmography as its reputation suggests: Its interest in spirituality’s coexistence with human fallibility is squarely in line with major themes throughout the director’s work, and from a formal standpoint, the movie’s beautiful, fluid imagery (shot by legendary cinematographer Roger Deakins) and propulsive editing style (the handiwork of longtime Scorsese collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker) are unmistakably Scorsesean. And while for the most part Kundun is unapologetically a slow film, an extended middle sequence depicting the 1950 Chinese invasion of Tibet is as taut and foreboding as anything in The Departed or Gangs of New York. Kundun is also a biopic, and as such belongs snugly in another sizable pocket of Scorsese’s oeuvre. The biopic is such a maligned genre that we often overlook the fact that a generous helping of Scorsese’s films fit into it, often squarely (as in the case of Kundun) and sometimes more obliquely (Killers of the Flower Moon’s tribute to the long-forgotten life of Mollie Kyle). Scorsese is often hailed as America’s greatest living filmmaker, an honorific I’m certainly not inclined to dispute, but he is almost assuredly our greatest director of biographical pictures. Raging Bull, Goodfellas, The Aviator, The Wolf of Wall Street, The Irishman: All of these films are biopics, without even needing much qualification. So what is it that makes Martin Scorsese so good at a genre that so many other filmmakers flail at, often in the most cloyingly Oscar-baiting fashion? Well, we can start with the obvious fact that Scorsese is simply a better filmmaker than most other directors. But a few more specific reasons stand out. The first is that Scorsese’s biopics mostly eschew the cradle-to-grave scope that’s often a stumbling block for other practitioners of the form. In films like Raging Bull, The Wolf of Wall Street, and The Irishman, for instance, we’re not given any insights into the subjects’ childhoods, thus deftly avoiding the sort of facile Freudianism that often bedevils the genre. Second, Scorsese’s biopics never stray into hagiography: Even when tackling a figure as monumental as Howard Hughes, The Aviator is as unflinching in its depiction of Hughes’ many demons as it is in his prodigious accomplishments. Even Kundun, a movie about a man considered by many to be literally divine, takes pains to render its protagonist as deeply human, overwhelmed by his spiritual and political responsibilities and often plagued by self-doubt. Which brings us to the third, and I would argue most important, quality of Scorsese’s biopics: His best works in this genre tend to take up the lives of people who wouldn’t normally be considered worthy of such projects. Henry Hill, Jordan Belfort, Frank Sheeran: Without Scorsese’s attention, these are people who’d barely even warrant Wikipedia pages. Even Jake LaMotta, a great fighter in his day, had slipped into such obscurity by the late 1970s that Scorsese had to be cajoled into making Raging Bull by Robert De Niro. Compounding their questionable historical significance, all of these men are essentially unreliable narrators of their own lives. Hill is a midtier mobster turned self-aggrandizing snitch, Belfort an unrepentant con man and fraud. The ending of Raging Bull finds an aging, bloated, battered LaMotta rehearsing his nightclub act into a mirror, desperately trying to burnish his own fading legend via bad poetry and On the Waterfront monologues. This aspect of Scorsese’s biographical films has sometimes led to controversy. While it’s now often hailed as one of the greatest films of this century, upon its release The Wolf of Wall Street was widely accused by some of uncritically celebrating the avaricious, debaucherous exploits of Belfort and his cronies. When The Irishman came out in 2019, Slate published a lengthy and quite convincing piece by longtime crime journalist Bill Tonelli that argued that the film’s source material, Sheeran’s as-told-to confessional I Heard You Paint Houses, was mostly fabricated. But such critiques presume the sort of literal-minded approaches to “realism” that are the province of so many lesser biopics, and that Scorsese’s films have always deftly subverted. If you’ve spent any time on the internet in recent years, you may be familiar with the filmgoing phenomenon of audiences not believing that certain, particularly indelible fictional characters aren’t actually real. The impulse that causes people to fruitlessly Google cinematic creations like Lydia Tár or László Tóth is, of course, a testament to the extraordinary writing and acting that bring these characters to life, and the filmmaking that makes their worlds seem so immediately real. Scorsese’s brilliance is for something like the opposite: He takes real-life historical figures and renders them so totally and irresistibly cinematic that we forget we’re even watching “biography,” even though most of these films are based on memoirs or, in some cases, actual biographies. I can’t imagine anyone watching Goodfellas and coming away wanting to meet the “real” Henry Hill; in the hands of Ray Liotta and Scorsese, the on-screen character feels as if he exists entirely autonomously. What must it have been like for Jake LaMotta, who died in 2017 at age 95, to have spent the last 37 years of his life with his public self so entirely eclipsed by Robert De Niro’s performance of him? And as for The Irishman, I don’t ultimately care if Frank Sheeran did everything or nothing that he claimed he did, because The Irishman never hides the fact that it’s a movie about a liar, particularly during its devastating final act. Whether or not Sheeran killed Jimmy Hoffa doesn’t really matter: The Irishman is about the kind of person who’d brag about murdering someone even if he didn’t, the sort of character Scorsese has been drawn to going at least as far back as De Niro’s own astonishing performance as Johnny Boy in Scorsese’s 1973 breakthrough, Mean Streets. (Johnny Boy is fictional, although the character is apparently so rooted in a boyhood acquaintance of Scorsese’s that said acquaintance tells Miller in Mr. Scorsese that he couldn’t bring himself to watch the movie.) The fundamental mistake most biopics make is in their presumption that the lives of “great” people are inherently interesting; Scorsese understands that it’s the lives of less-than-great people that are often much more so.