By Emma Gleason

Copyright thespinoff

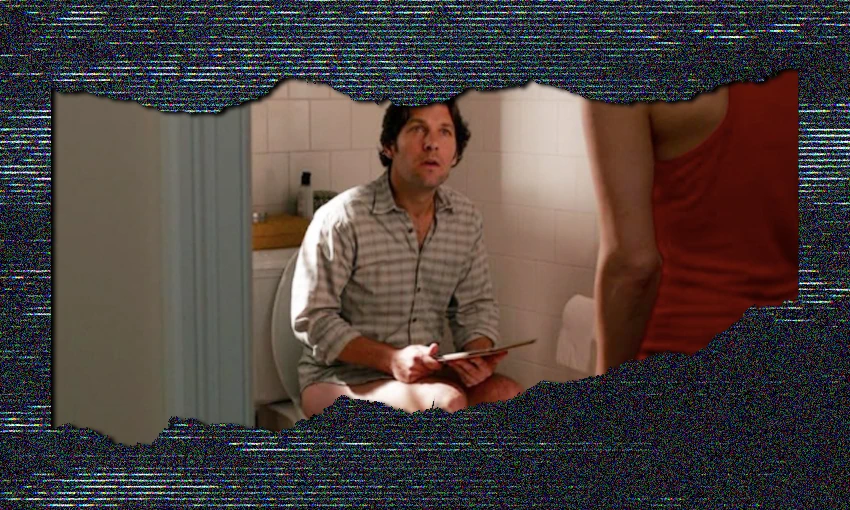

We’re witnessing the worst things in the world while sitting on the toilet.

Check your phone first thing in the morning and, depending on the news cycle, you may be greeted with graphic violence, served up amid a stream of other “engaging” content: cute dogs, protein maxxing tips, celebrities’ new faces, podcaster profundity, videos of someone quite literally touching grass, outpourings of anger, another cute dog. It’s a taste of the feed in 2025.

*Looks up from phone, eyes bloodshot* Wait, where are we?

Talking about the feed and what we’re seeing on it. Algorithms have become the dominant paradigm for social media platforms, and these automated computations largely control what users are served. Feeds are individualised, randomised flows of information, more addictive (due to both content and delivery) and more attuned to our personal tastes (through data insights) than ever. It’s opaque by design, and what we’re shown is influenced by myriad factors: our demographics and behaviour, what’s trending, and content categories deemed important by the platform. It’s all very mysterious and closely guarded.

Where “the feed” once consisted of people we followed, it now incorporates suggested accounts, trending topics and content that will keep you on the app for longer (attention = $$$), much of which is now attention-grabbing, short-form videos. There are Instagram Reels, YouTube Shorts, and video on X and Reddit too. And then there’s TikTok, considered so powerful that the US tried to outlaw it (India actually did) and New Zealand blocked it from government devices “due to ongoing privacy and security concerns“.

Algorithmic video feeds encourage “lean back” engagement, serving the passive viewer with an endless stream of stuff, hastened by the swipe of a thumb, surprise baked into the dynamic. Instead of reading about a catastrophe, we watch it happen minutes afterwards or, in some cases, live. You never know what you’ll see next. It’s enough to make someone scared to scroll.

“With recent news events and the wider ongoing polycrisis, I can understand why people might be avoiding their social media feeds,” says Alex Beattie, media and communication lecturer at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University. “It’s quite distressing knowing there’s violent content out there that can play automatically on your news feeds, without your consent.”

It’s difficult to know exactly how common that feeling is. “We’ve only started researching news avoidance in the last couple of years and we also know that people disconnect from their social media feeds for mental health reasons. We need more research to determine if news avoidance or social media scrolling angst is increasing. What we do know is that globally, news avoidance peaked in 2024 and dropped a little bit in 2025.”

Why does the algorithm feel more hectic?

Beyond our now-standard doomscrolling, people feel like they’re seeing a lot of graphic, violent or divisive content in their feeds. “The algorithms are designed to maximise engagement or a response, and graphic or divisive content fits that category,” Beattie tells The Spinoff. “And following the 2024 election of Donald Trump, platforms like Meta have stripped back their content moderation policies in order to appease free-speech advocates.”

Meta made sweeping changes in January. It disestablished fact-checking teams (experts warned of “hate, disinformation, and conspiracy theories” online that can “spur real-world violence”) in favour of community moderation, removed restrictions on subjects like “immigration and gender”, relaxed its hateful conduct policy and phased political content back into feeds. (Mark Zuckerberg acknowledged that more harmful content would be on Meta’s platforms.) X has loosened up in recent years too, adding an algorithmic “for you” feed and relaxing rules around graphic posts (including “violent content”). It uses community notes to police user behaviour, while Reddit relies on volunteer moderators to maintain its forum standards (and any legally restricted information). “Gory, gruesome, disturbing, or extremely violent content” is against TikTok’s rules, though content “shared in the public interest may be allowed”. Last month, the company started laying off human moderators as it scales up AI automation.

There’s also just more bad news. Algorithmic feeds are also often the first, and, for some, only place we learn of breaking events and current affairs. Global studies show that 54% of 18- to 24-year-olds and 50% of 25- to 34-year-olds use social media and video networks as their main source of news. Whether extreme events are actually happening more frequently or we’re just hearing about them more often is hard to say. “What we do know is that extreme events are increasingly mediatised or captured by smartphones and shared through social media. This can make it feel like they are happening more frequently,” Beattie says.

This thing is literally in my hands. So what settings can I change?

Considering all these updates, do users have much control over their feeds? “Yes and no,” says Beattie. “Users can change their ad preferences or topics of interest on each platform, which can influence what content the algorithm delivers. You can also download widgets or apps that can remove or change the news feed. But these changes are largely cosmetic and won’t stop viral content appearing on people’s news feeds. What content we see gets to the heart of the platform business model. It is propriety and not in their interests to make it open and editable to users.”

If it feels hard or confusing to find and change specific settings on an app, that’s because it’s probably intended to be. “It’s called a dark pattern,” says Beattie – it’s an industry term describing elements of online interfaces and user experience that nudge consumers towards certain behaviour, or make it harder to opt out. “These design choices are deployed to maximise engagement and direct users to outcomes that benefit the platform.”

Beyond tinkering with app settings (and searching “cute dogs” to influence your algorithm), is there anything else people can do to control what they’re seeing? “Unfortunately, the most effective thing to do is itself extreme: deleting your social media account and refusing to give the platform your attention,” explained Beattie. “These platforms will only change when people leave them.”

OK, I changed my settings and put my phone down for a bit. What’s everyone else doing to address this?

This week Amnesty International Aotearoa New Zealand and Inclusive Aotearoa Collective Tāhono launched a campaign against online harm, #NoHarmware. It calls on the government to regulate tech companies and establish a legal framework that can “hold online platforms responsible for the harm they knowingly cause through the design of their platforms, and in the way content is promoted or censored”, including livestreamed violence and disturbing material. It also calls for transparency around algorithms and their impact, alongside what it sees as a “fundamental design flaw” driving harmful content in feeds, the prioritisation of engagement.

This joins ongoing initiatives, like charitable foundation The Christchurch Call, which aims to eliminate violent extremism and offensive material in online spaces. Its work includes research into the role algorithms play in radicalisation, and CEO Paul Ash spoke to Toby Manhire earlier this year about the changes at Meta.

Netsafe receives around 500 reports of objectionable content each year. It has advice for what you can do if you see upsetting stuff, and can be contacted (via email, online form, free phone 0508 638 723 or texting 4282) for support and advice. For those with kids exposed to feeds, it also runs webinars on navigating harmful content.

Young people are also a focus of proposed action. There’s a parliamentary inquiry under way, with a report expected by late November, as well as a National Party member’s bill in the biscuit tin that aims to ban under-16s from social media, as Australia has done. Criticism of a proposed ban includes data privacy and enforcement, causality, isolation and censorship, and that without platform regulation, “systems that foster harm continue unchecked”.

Internet NZ disagrees with a ban too, arguing that the policy ignores harm caused by “exploitative algorithms” and “consent loopholes”. Instead, it suggests measures like banning exploitative designs for minors, and establishing an “independent digital regulator”. The problems it outlines, including “neurologically exploitative recommendation engines”, affect people of all ages. As Alex Casey pointed out earlier this year, perhaps we should all be banned from social media.

What about our behaviour offline, could that be better?

Good question.