South Carolina doesn’t get much authentically good news about public education. What passes for celebration-worthy is usually along the lines of “our test scores didn’t drop as much as the national average,” or “we didn’t start the school year with as many teacher vacancies as the year before.” Occasionally we even get tiny little improvements on standardized tests.

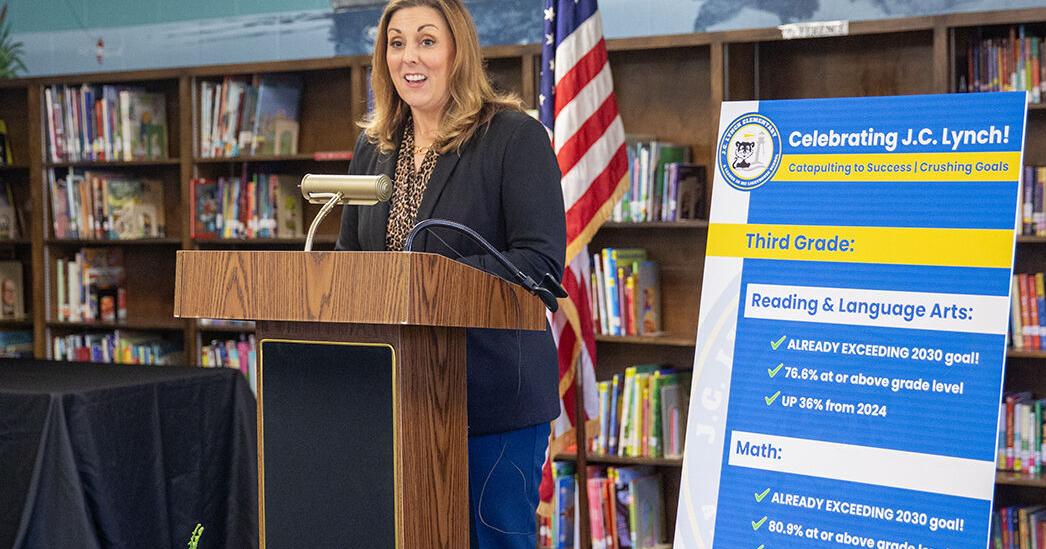

But earlier this month, we got some news we can actually cheer, when Education Superintendent Ellen Weaver announced dramatic improvement in children’s reading scores. As The Post and Courier’s Anna B. Mitchell reports, the number of students who met or exceeded grade-level expectations on this spring’s SC READY tests jumped six percentage points, to nearly 60 percent, with even bigger improvements in lower grades; math scores showed the sort of marginal gains we’re accustomed to celebrating.

Ms. Weaver credited the state’s deliberate shift — pioneered under her predecessor Molly Spearman, aggressively advanced by her and supported enthusiastically by the Legislature — toward a structured, phonics-focused approach to reading often referred to as the “science of reading.” That was aided by focused state assistance to poor districts, new language arts standards adopted for the 2024 school year that better spell out what students need to know, new textbooks aligned to the standards and the rollout of “LETRS” training for all kindergarten through third-grade teachers that has been getting rave reviews from teachers.

Abby Duggins, the Education Department’s chief academic officer, cautions against considering these gains an overnight success story. As with artists who suddenly achieve renown after working for years or even decades in obscurity, she told us, the reading improvements were built on “a really long runway and a carefully planned runway.”

The shift to the so-called science of reading is part of a nationwide trend toward using the explicit, systematic and direct teaching of foundational skills, including phonics, to teach children to read. Everybody used phonics back before we started worrying about whether we were teaching all kids, and so we didn’t have the standardized testing data to show how well it worked. States changed to “whole language” in the 1960s and continued until a 2000 federal study concluded that phonics worked better. But that declaration got caught up in politics, the “reading wars” ensued, and it took two decades for the change to take.

South Carolina was an early adopter, but even here it took a decade to get our reading standards to the point where they clearly spell out what students need to learn at each grade level and to teach teachers how to teach them.

Although S.C. education officials expected dramatic results as a result of the new approach and the teacher training, even they were a bit surprised by the big jump, which they expected to occur in the tests that will be administered this coming spring, after all teachers have finished their two-year training and after we test the first cohort of third-graders who got started reading under the new regime. That means we should see another impressive jump a year from now — followed a couple of years later by big improvements resulting from the Palmetto Math Project, a similar program that’s just getting started this fall.

But there’s a cautionary tale here, based on our own experience in South Carolina and if not human nature then legislative nature. Clearly, the shift back to phonics was needed, but it took the Legislature a long time to complete it and involved fits and starts: Over the course of a decade, lawmakers approved four different testing regimes, three of them in three years, as a result of three different sets of state teaching standards. That was in part a result of those reading wars, but in part a result of legislative meddling, as lawmakers kept trying to get better numbers by changing the test — which might get you better scores but will never get you better learning.

The Education Department appears finally to have hit on a successful formula — one our current Legislature supports. And while it’s tempting to ask why no one came up with this sooner, the fact is that it’s been a work in progress across the nation. The more important fact is that what we need now is for the Legislature to not screw this up.

There are a lot of things lawmakers need to do to improve public education, among them continuing to provide the funding and professional support to battle a nationwide teacher shortage, providing school districts and even principals the tools they need to entice the best teachers and remove the least capable, and intervening more aggressively when school districts or even individual schools don’t get the job done. That’s what they need to do. What they don’t need to do is decide they have a better way to design state education standards and curricula and standardized tests. What we have right now is working; we need to allow it to keep working, unless and until we have clear evidence that a change is needed — evidence that will not come from politicians.

Click here for more opinion content from The Post and Courier.