Copyright truthout

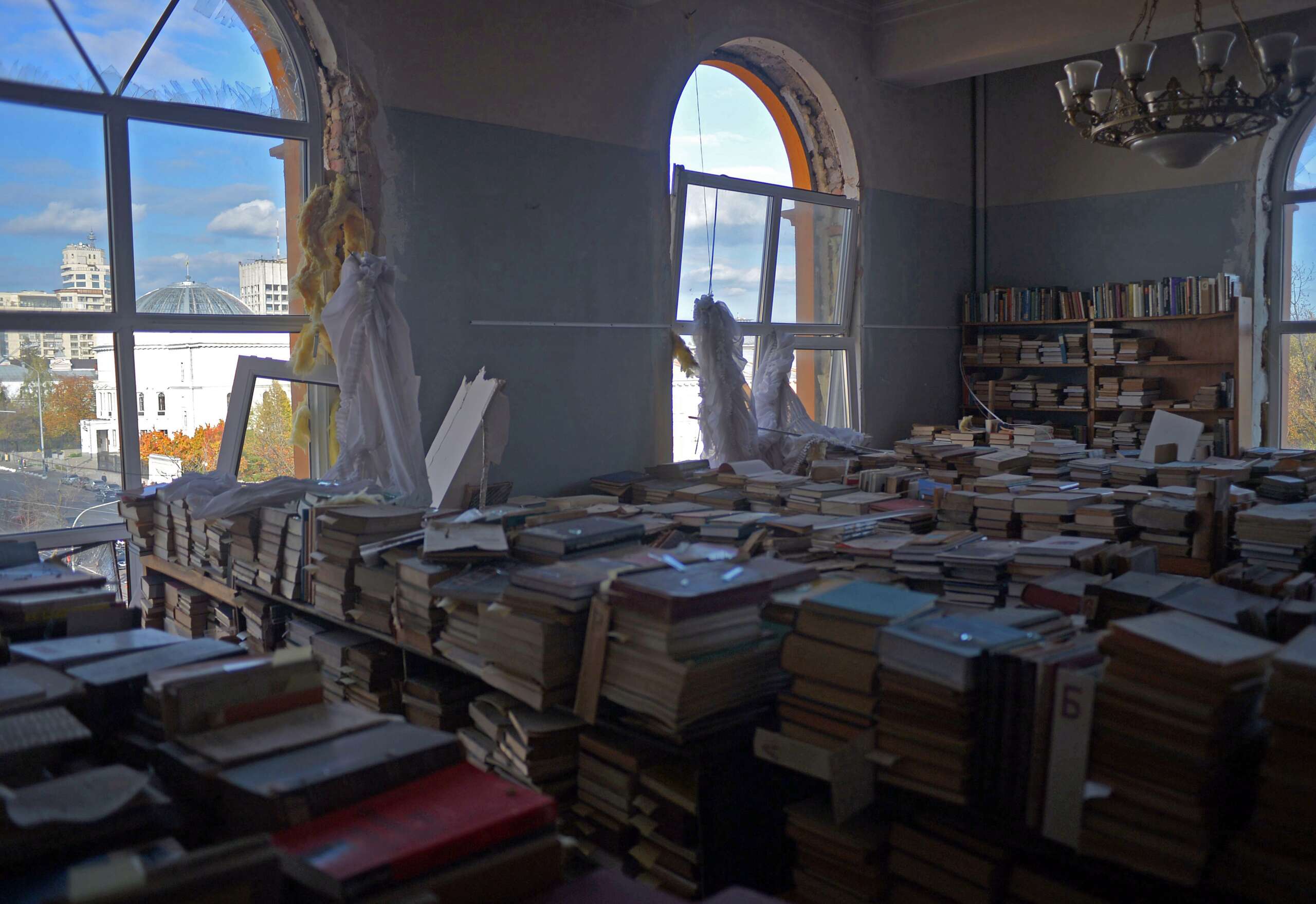

When Yulia Berg was in her second year at Odesa I.I. Mechnikov National University in Odesa, a strategic port city in Ukraine, her university life, once defined by lectures, was suddenly rewritten by war. “Everyone experienced the beginning of the war in their own way, but for me, it meant missing out on student life,” Berg told Truthout. Berg graduated in May 2025 with a degree in international relations, and lived the bulk of her college experience during wartime, at times hearing missiles just outside of her apartment. Berg is far from alone. Russia’s invasion has forced school-aged Ukrainians to contend with the cruel realities of war — and, in many cases, reevaluate their views on the role of civic life and education in their country. Berg saw major shifts on her university campus after the war began. Some, like new safety protocols such as air raid drills, emergency evacuation apps, and evacuation procedures, were to be expected. But socialization and student life also changed. “In my first year, I was able to make new friends,” Berg said. “We formed a tight-knit group, sat together in classrooms, bought each other sweets, shared smoke breaks with professors, debated ideas, and dreamed together.” “After the start of the full-scale invasion, none of my friends returned to university. They all left, and there was no more opportunity to build new connections. That affected me for several years.” Berg told Truthout that most of her college friend group decided to flee Ukraine in search of safety. Some immigrated to other European countries with their families, who also sought a better life elsewhere; others sought safety within Ukraine, but moved further away from Russian attacks. Since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, roughly 10.4 million Ukrainian people have been displaced, a number that includes people who left their homes for other parts of the country as well as immigration to other countries abroad. According to the European Union statistics portal Eurostat, 31.2 percent of them, or around 2 million people, were teenagers and young adults. A large share of them would have likely gone to Ukrainian universities. Instead, they were forced start their lives from scratch. Those who stayed did not have any chance at normalcy. In February of 2022, Ukraine declared official military status in response to the Russian invasion — a legal status that allows the government to impose curfews, restrict movement and prioritize military needs over civilian needs. As a result, all higher education facilities were forced to teach on Zoom, as they previously did along with the rest of the world during COVID-19. Berg said that the feeling of unsafety, intense academic pressure, and overall isolation slowly affected her ability to study effectively. “Laziness crept in, I started skipping classes, deadlines burned, and I began questioning why I was even studying here in the first place.” What began as fatigue soon enough turned into something deeper — fear. “Almost every night I was haunted by nightmares,” Berg said. “A missile hitting me, or stepping on a landmine, or saying goodbye to my family, or a nuclear weapon falling on my city, and the last thing I see before waking up is a giant mushroom cloud of fire and smoke. And then you wake up and find yourself in a reality where you have to run to the hallway, grabbing your cat and covering your ears, because just a few kilometers away a warehouse or an airfield is being bombed. That kind of thing doesn’t leave you untouched.” Such experiences reflect the conditions under which Ukrainian higher education continues to function. As of 2025, nearly 3,600 higher education establishments have been damaged across Ukraine due to the war, according to the UNHCR. Over 400 schools were destroyed completely and/or occupied by the Russian Federation, with no ability to be repaired. That caused significant changes to the academic infrastructure inside Ukraine — at one point all institutions switched to online or hybrid learning because of the unpredictability of war. Some universities combined due to budget cuts and shrinking student numbers, while others shut down altogether. Odesa National Economic University was one of the first schools to re-open in person after the invasion. The school’s rector, Kovalev Anatoly Ivanovich, told Truthout that the war’s early months required deep work to keep the university functioning. The university had to build shelters in old basements that were not initially meant for hiding from explosions; in some cases they used old bomb shelters left from World War II. However, in less than five months, the school was able to prepare shelters in every university building and dormitory. In September 2022, as the events of the war became more predictable to the public and the authorities, the university was able to officially resume classes in person despite the active military actions and ongoing martial law. “It was very important for us to give our students a normal university experience,” Kovalev said, “And it allowed professors to work with students face to face.” Kovalev also said that the university received generators to assist with power shortages thanks to help from the Ukrainian state as well as from abroad — specifically, the school’s university partners from Germany, Austria, and the United States. Natalya Vyacheslavivna Zakharchenko, a professor in the Department of Economic Law and Business Management, has been teaching at Odesa National Economic University since 2021. She told Truthout that this war has led to a major shift in values: Safety has become the main priority across the entire university ecosystem — for faculty, administration, and students alike. “As soon as there’s an air raid alert, there’s no discussion — we immediately go to the shelter, and we even continue holding lectures there,” Zakharchenko said. “No one wastes time, you understand?” Zarkharchenko said that the infrastructure at her university was not directly damaged by Russian attacks. But the danger was not abstract. She herself witnessed a missile hit a building right in front of the school, reducing it to rubble. “God saved us,” she recalled, “A nearby building was affected, but we have a shelter, and it’s reliable. It saved the people who ran from that building and took cover in it.” Other universities still functioning across Ukraine are also finding their day-to-day operations disrupted — not just by air raids, but the massive exodus of students who are fleeing frontline regions. According to a recent UNESCO analysis, there was a 21 percent drop in student population across universities, with 41,500 fewer graduates taking the university entrance exams in 2022, compared to 2021. Zakharchenko Vadym Mykolaiovych, a vice rector of Odesa Maritime Academy, said that many faculty members and students have gone abroad, settling in the European Union. Zakharchenko says that has meant a serious hit to Marine Academy’s operations, with young men leaving before they are beholden to the army at the age of 18, and many young women seeking education and safety abroad. “Yes, Ukraine’s demographics were not great even before, but now a lot of young people, especially boys, even in their final years of school, are leaving the country and trying to enroll in educational institutions abroad,” Zakharchenko told Truthout. “And that’s where we feel a very serious drop in the number of applicants across all universities.” Many young adults from Eastern Ukraine, areas most prone to Russian attacks, moved westward, seeking safer conditions — from Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv to cities further West, like Kyiv, Lviv, and Odesa. Schools like Taras Shevchenko University in Kyiv, one of Ukraine’s largest institutions, received a prominent wave of students from harder hit-areas. Ihnatyuk Anzhela Ivanivna, dean of Taras Shevchenko University’s economic faculty, said that she has witnessed this shift firsthand. “If we enroll around 600 first-year students, about 10 percent of them are displaced persons — and this year, it might be as high as 20 percent,” she commented. “The number is simply increasing every year. Of course, they receive all the benefits they are entitled to under the law, and we provide everything we possibly can on top of that.” Still, Ihnatyuk noted that while undergraduate enrollment has remained relatively stable, there has been a significant drop in graduate-level participation, particularly in master’s degree programs. She said that Ukrainian students are actively starting to follow international practices, where people don’t go into a master’s program after completing a bachelor’s degree; before the war, obtaining a masters straightaway was encouraged. She also noted that this tendency has to do with obvious economic issues that Ukraine is facing. “After earning a bachelor’s, people go to work, gain experience, and then decide what they want and how they want to continue — that’s one path,” the dean explained. “The other path is that many, not only bachelor’s graduates, but also prospective master’s students are going abroad to study, and later stay there.” As universities contend with these rapidly changing demographics, they are also forced to deal with additional new budgetary constraints: Higher education in Ukraine is being severely underfunded due to the military needs. Under martial law, the Department of Education’s resources are lacking significantly compared to previous years. Universities across the country felt that shift. As of 2022, the part of the government budget spent on education dropped from 14.25 percent to 8.49 percent. Rectors and deans say that the declining student numbers directly affect university finances, too. Some Ukrainian universities are forced to operate on a per-student funding basis, meaning they rely almost entirely on student-paid tuition fees to stay afloat, without government assistance. When enrollment drops, so does financial viability. Some schools have been forced to face difficult decisions about whether they can continue to exist independently. Nowhere is this more visible than Odesa, where the country’s two largest maritime institutions, the Odesa Marine Academy and Maritime University, are planning to merge. This move, Zakharchenko said, was accelerated by wartime conditions. When overall enrollment began dropping across both campuses, he said, the state suggested that a merge would be the only sustainable option. “I don’t want to comment again on political decisions, but it seems to me that Ukraine no longer has any other path,” Zakharchenko commented. “Some kind of merging must take place, because institutions are shrinking due to declining enrollment. When a university becomes small, it’s very difficult to manage; too few students, yet all the departments and resources, such as academic offices, still need to function. They become, let’s say, economically weak. Unstable.” At Taras Shevchenko University in Kyiv, Ivanivna said that the financial struggle is still an issue for most schools, even those that receive higher government financial support. As a National University, a designation that grants higher status and priority funding from the state, Shevchenko receives more financial support than regular state universities. “Our university is perhaps the only one in Ukraine that has a double coefficient, meaning we are funded at a rate of two,” she explained. “And that fortunately allows us to pay our professors more than other institutions can.” In Odesa, Zakharchenko still manages to stay hopeful despite the financial struggles that educators are facing with lower pay rates and difficult working conditions. “We’re not complaining, of course. We don’t know what the state can offer us as educators right now, given the ongoing war,” she said. “But I truly believe that with time and development, we will rise again and turn our attention back to education, which has always been strong in our country. It still is strong, but now it also deserves fair pay.” Most agree that the education cuts are a necessary sacrifice in wartime. However, not everyone sees them as temporary. Berg, the student in Odesa, is less confident that the underfunding was simply a wartime decision. “Of course, today military needs are the top priority, but even before the war, not enough funding was invested in education and educational institutions,” she said. “That’s very sad, because my country has enormous potential.” But the financial losses across Ukraine’s schools pale in comparison to the human ones. At Shevchenko University’s campus in Kyiv, in the heart of Ukraine’s capital, small bushes bloom quietly across the lawn — each one in memory of a student who left for the front and never returned, serving as a symbol of the highest cost the country has paid in its fight to shake off occupation.