Copyright Chicago Tribune

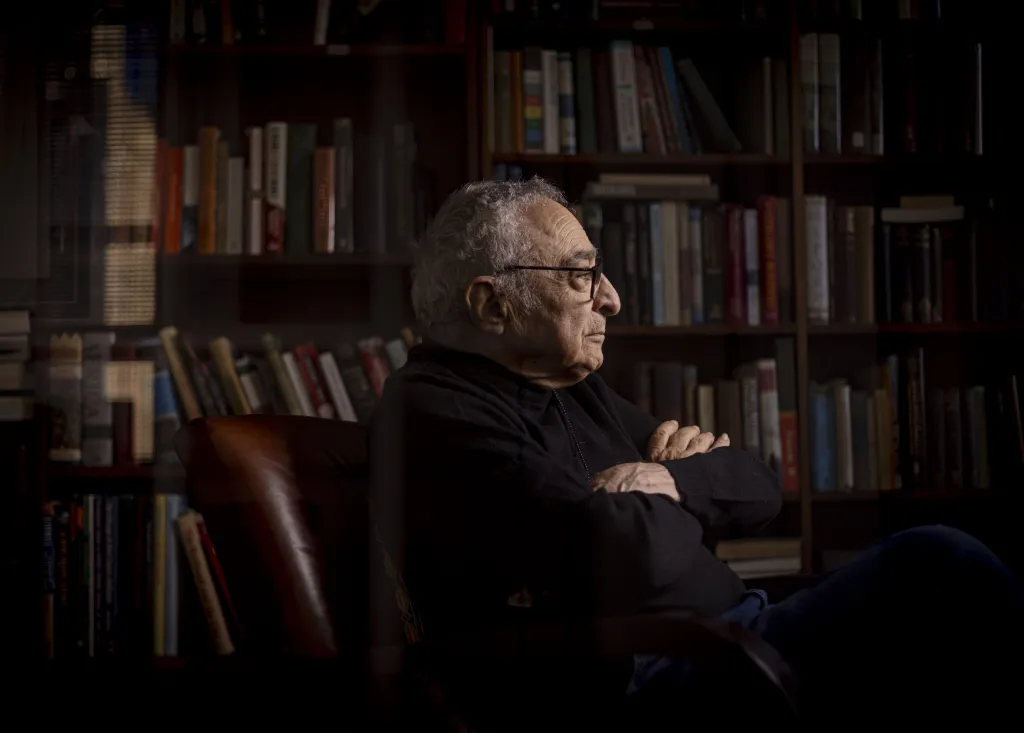

I’ve been asked to introduce myself and say farewell in 1,300 words. So I’ll get right to the bottom line. “Ron Grossman was born during the Great Depression, wasn’t very athletic, and is Jewish.” I was also a first-born son and obligated by Talmudic law to serve as a Levite, an assistant to a cohen, a priest. But there was an alternative. Parents could pay a priest to be relieved from that duty by giving a cohen some silver coins. As he was leaving our home, my cohen looked around a virtually empty apartment and said: You need these more than I do. Take them. In grade school, I was virtually guaranteed to be chosen last for softball games. To avoid embarrassment, I took refuge in the Albany Park Public Library. There, I found novels set in different neighborhoods, yet just like mine. With those books, I found my way to Little Italy, Chinatown, Pilsen and Little Village. Seventy-five years later I still get a kick out of those ethnic explorations. My parents dearly hoped that I would emulate my Uncle Ben, who had gotten a degree in engineering. My uncle and aunt, my father and mother, along with me, my brother and two cousins, lived together in a one-bedroom apartment. For high school, I chose Lane Tech because my parents were convinced that if you did something with a T square and a triangle, you would always make a living. I majored in architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where Mies van der Rohe presided. His assistants read lectures as if praying to a deity. “What do we build with?” professor Alfred Caldwell would ask us. “Steel and concrete?” one student answered. “No,” Caldwell said, poking the student in the chest. “We build with head and heart!” But I realized my talent was lacking, and the architecture curriculum doesn’t leave much time for books. So I transferred to the University of Chicago, telling my parents I was just taking some time off from architecture. There I was introduced to the Great Books, philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle, Nietzsche and John Stuart Mill. But curiously, the University of Chicago made me unfit for academic life. My first job was at the University of Nebraska, where the department secretary asked if I wanted tickets to the faculty football cheering section. I said no thank you, not recognizing that it wasn’t really a question. My answer immediately made me ineligible for a second year there. I was lucky to land a position at Lake Forest College. And to drift into newspapering. In the early 1970s, the Chicago Board of Education wanted to relieve overcrowding in Black schools located to the east of Gage Park by moving some students to Gage Park High School. Residents of that largely white Southwest Side neighborhood were opposed; they wanted to keep the school for themselves. The daily newspapers were portraying the dispute as a moral question, which seemed too simple to me. I spent time in the area, listening to the concerns of the people involved, and wrote about my findings in the Chicago Journalism Review, a periodical written and edited by working journalists. The Tribune bought the piece and reprinted it as a series, and lo and behold my journalism career was launched. As a history professor, I told students stories that I read in textbooks. The Tribune sent me to witness historical events. In 1985 I saw and reported on a pre-Christian memorial service in a small village in the Mani, a remote southern district of Greece. The ritual involved several elderly women taking turns chanting the history of the village from mythological times to the present, enshrining the deceased’s name and status in the oral record. One of the ritual chanters startled me by asking my name, where I came from and details about my family. She wove that into the history of the village so it would be told every time another villager dies. My name will be remembered on that mountaintop in perpetuity. How’s that for a byline! But now I’m retiring, having written more than 2,000 articles and columns for Tempo, main news, Metro, Perspective, Opinion, the magazine and A&E, plus book reviews, travel pieces and of course Flashback and Vintage Chicago Tribune. I’m closing my notebook in the midst of an unprecedented story. The president of the United States has reduced the American government to the level of a mobbed-up restaurant. If a reporter glorifies Trump, he can otherwise write what he wants. That’s called extortion. Recently Trump has staffers going through the Smithsonian Institute. America’s hall-closet shelf, it stores bits and pieces of our national story. Trump thinks it focuses too much on “how bad slavery was.” Ten million Africans and their descendants worked as slave labor before the 14th Amendment abolished slavery. Their lives were dictated by an overseer’s whip. If Trump is concerned about the larger story of slavery, he wouldn’t be pillaging the Smithsonian. He’d be concerned with protecting “Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936 to 1938,” interviews with former slaves preserved in the Library of Congress. One aged man reported: “My brothers and sisters were bid off first, while my mother, paralyzed by grief, held me by the hand. Her turn came, and she was bought by Isaac Riley. Then I was offered to the assembly of purchasers. “My mother pushed through the crowd to the spot where Riley was standing. She fell at his feet, entreating him to buy her baby as well as herself and spare her one child at least. (He refused.) I was then 5 years old.” In the Dred Scott case of 1857, the Supreme Court ruled that a slave hadn’t the right to ask for the court’s intervention. Nearly a century later, in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954, the court ruled that separating Black and white children in schools was illegal. Now Trump wants to obscure that historical record. And the Supreme Court, which has set limits on what elected officials can do, decided in Trump v. the United States 2024 that the president’s power should be virtually unlimited. Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her dissent: “Argument by argument, the majority invents immunity through brute force. Under scrutiny, its arguments crumble. … No matter how you look at it, the majority’s official-acts immunity is utterly indefensible.” I don’t think I’ll live to see a happy ending to the current story. Yet I had an experience that suggests my children will see a restoration of the rule of law. My wife and I went to the No Kings demonstration on Oct. 18. It had been a foreboding season. Trump called hundreds of generals and admirals home and said he’d told Pete Hegseth, head of the renamed Department of War, that “we should use some of these dangerous cities as training grounds for our military — National Guard, but military — because we’re going into Chicago very soon.” On the corner of Michigan Avenue and Randolph Street, a small group of folk singers stood. One held up a page of sheet music as if they feared blowing the lyrics. My wife and I could have finished the song for them. Woody Guthrie wrote it during the Great Depression. We sang it during the Red Scare in the 1950s and during the Civil Rights Movement. “As I was walking that ribbon of highway I saw above me that endless skyway I saw below me that golden valley” Finally, a word to you readers. You have nourished me by engaging in conversation and argument. This has been a gift of inestimable worth. And I will sorely miss your presence in my life. So I will worry less about you if you don’t forget Woody’s message: “This land is your land, this land is my land This land was made for you and me.” Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Marianne Mather at mmather@chicagotribune.com. Ron Grossman can be reached at grossmanron34@gmail.com