Newly discovered prehistoric artwork suggests how a pioneering sect of desert nomads, unknown to history until now, carved out an existence about 12,000 years ago in the harsh environment of northern Arabia.

At four remote sites near Saudi Arabia’s Nefud Desert, researchers are puzzling over 130 life-sized animal images emblazoned on rocky outcrops. Wild camels dominate the carvings: 90 of them run alongside other ancient beasts that once roamed the arid landscape. Sweeping antlers of sure-footed ibex appear prominently. Ancient horselike equids are shown with their young. A depiction of an auroch, an extinct, hulking bovine that required plenty of water, suggests wetter environs—but only slightly wetter, say the archeologists who discovered the artwork. Their sediment analysis reveals seasonal lakes at two of the sites: ephemeral watering holes that were possibly shared by hunter-gatherers and other animals. And the camel etchings give clues to the circumstances of the encounters. At the time, livestock had yet to be domesticated, and camel herds still ran wild. Indeed, the desert-adapted camel stands out as the ancient artists’ favorite subject.

“I wonder whether these humans looked at camels and thought, ‘Wow, these guys, they really know how to cope when there’s no water,’” says Maria Guagnin of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Jena, Germany. She co-authored a paper on the art’s discovery, which was published today in Nature Communications.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

There was so little water in northern Arabia at the end of the last ice age, roughly 11,700 years ago, that most experts had assumed it was uninhabitable at that time, Guagnin says. But now artifacts that the new study’s researchers unearthed—such as stone tools, arrowheads and hearths, some of which were found immediately adjacent to the carvings—show that a highly mobile population thrived there for more than 2,000 years, she says.

In the rock art, all the camels appear as these animals do in winter: with furry coats and necks swollen from mating vocalizations. Winter was the region’s rainy season, which means camels and their human admirers likely congregated around lake beds full of water, the researchers say. These connections raise the possibility that people were following camels across the desert on winter migrations, says archaeologist and study co-author Ceri Shipton, who was excavating the site, known as Jebel Misma, when his team spotted a spectacular caravan of camel carvings on May 14, 2023.

On that morning, one of Shipton’s sharp-eyed assistants, Saleh Idris, looked up and exclaimed, “Jamal, jamal!” (camel in Arabic). Shipton looked up as well and, he recalls, “suddenly the sun came round enough so you could see them on the whole cliff, and I was like, ‘Oh, my God, it’s covered in them.’”

“It’s a bit of Indiana Jones,” Guagnin says, “because you can only see it for about an hour and a half in the morning, when the sun rises, and it comes up over the mountain, and it hits it just right. And then the sun rises a bit further, you lose all of the contrast, and it’s invisible until the next morning.”

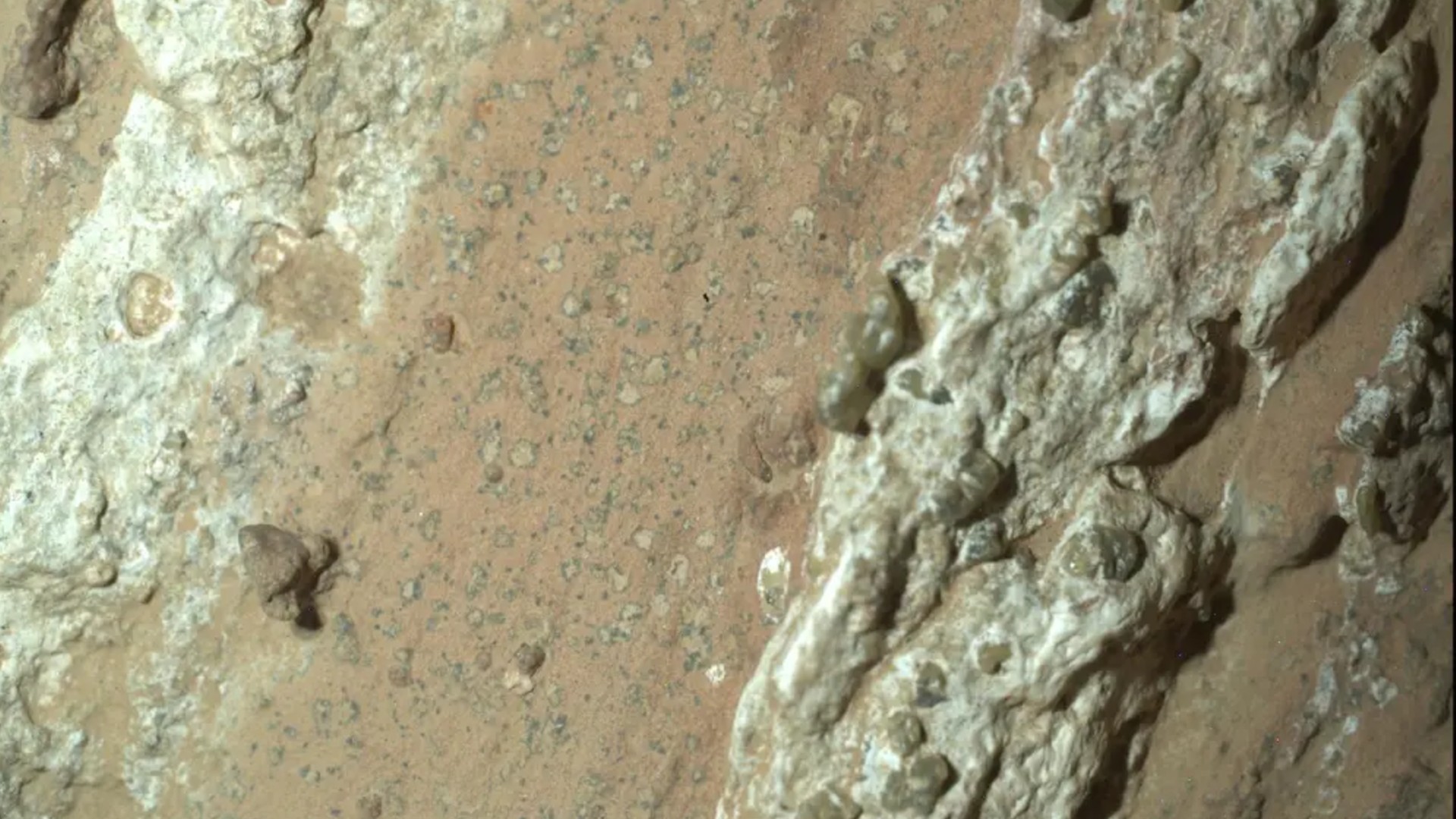

These carvings sit just above a ledge barely wide enough to get a foothold, on a sheer rock face more than 100 feet high. “So that means they had the rock surface directly in front of their nose, and at no point would they be able to see the whole animal. They must have had an engraving tool and just basically hammered it…, going from one side to the other, and somehow created this whole animal along the rock surface,” Guagnin says.

Many of the camel carvings are layered one on top of the other and vary slightly in style over time, from realistic to more cartoonish and abstract—a progression, Guagnin says, that could mean the artists were developing a shared concept of the camel. The continuous effort to update the carvings establishes their use over long periods. The researchers propose they were intended to guide thirsty hunter-gatherers to water sources that were often concealed behind boulders and sandstone formations and to mark access rights.

Guagnin herself was guided by the camel art at Jebel Aarnaan, another site that is also described in the paper. “If you go behind the rock, you realize it opens up into a little valley that leads up a mountain,” she says. “And the whole valley up the mountain is flanked with rock art. And it turns out it’s actually a shortcut across to the other side where there is a lake, so it connects you to the nearest water source without having to go the long way round.” There and at Jebel Misma, the team found stone-hammering tools left behind by the artists in layers of sediment dating back 12,000 years. That makes the carvings several millennia older than similar art found elsewhere in Arabia, says Guillaume Charloux, an archeologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research, who wasn’t involved in the study. Their age “profoundly transforms … our understanding of prehistoric art in the Arabian Peninsula” because it means the camel creations coincided “with the peak of cave art in Western Europe,” he says.