TORONTO – In an America splintered by culture wars and, increasingly, by targeted violence, Robert Redford somehow belonged to everyone. Might his life and career offer lessons for powerful figures who prize access and short-term self-interest over the long-term common good?

A quintessential movie star whose life was a paragon of public and private virtue, Redford turned advantage outward. Not only did he give us enduring films, but he founded a film festival – the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah – that has consistently discovered talent and created jobs, and he made environmental conservation a mainstream cause before it was fashionable. He converted private capital into public goods.

The remembrances following his death on September 16 captured the breadth of his pursuits, and, notably, they were as bipartisan as they were sincere. By tirelessly leveraging his personal charisma and talents to advance a unifying vision of America and what it could be, he was an exception in an age of cynicism and polarization.

I was fortunate to see Redford and what he represented firsthand. When I was growing up, the Sundance Kid himself came to my New York City school, and Redford made his way over to dance with me. Unimaginably handsome with a gentle yet piercing gaze, he was a living legend, giving his time freely to children.

No wonder the mourning has been so personal. Jane Fonda, his longtime friend, said she couldn’t stop crying. “One of the lions has passed. Rest in peace, my lovely friend,” said Meryl Streep. Though Redford criticized Donald Trump (no fan of Hollywood liberals), the president didn’t swing back. Even he acknowledged Redford’s star power: “There was a period when he was the hottest. I thought he was great.” Across the board, right-leaning celebrities, such as Rob Lowe and Sylvester Stallone, have been as respectful and admiring as those on the left.

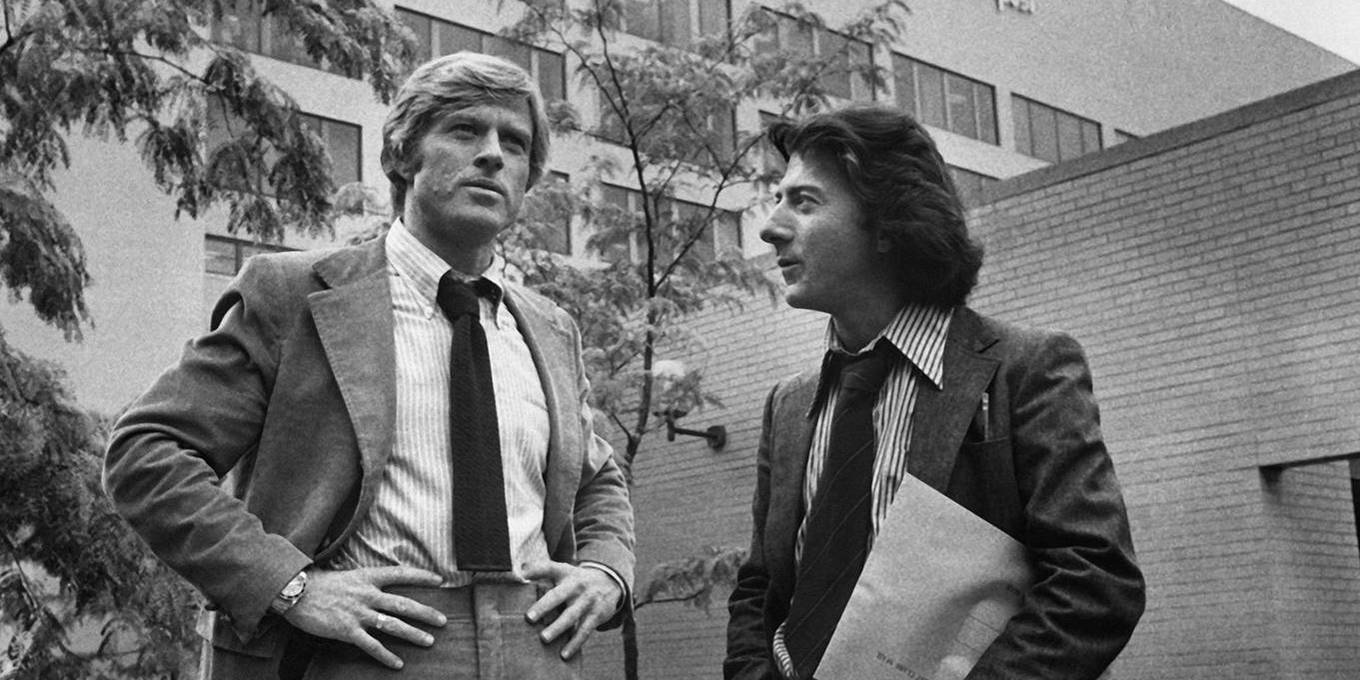

Bob Woodward, whom Redford played in All the President’s Men, put it well: “He used any platform he had to help make the world better, fairer, brighter for others.” While Leonardo DiCaprio underscored Redford’s “unwavering commitment to protecting our planet and inspiring change,” Gary Herbert, a former Republican governor of Utah, hailed him for turning two acres “into a beautiful resort, a financially booming retail enterprise and an industry-disrupting, world-changing film showcase” that employed thousands and has brought roughly $1 billion to Utah’s economy. According to the filmmaker Ron Howard, it was Sundance that “supercharged America’s independent film movement.”

Together, these voices illustrate the breadth of constituencies Redford’s work touched. The films, of course, explain his reach. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid reinvented the quintessentially American myth of the Old West without sneering at it. All the President’s Men made diligence thrilling and accountability heroic, reshaping how Americans viewed both journalism and democracy itself. Ordinary People, Redford’s directing debut, used a sense of quiet grief to carry the frame, bringing character-driven portraits of personal struggle into the mainstream at a time when the mainstream was dominated by spectacle.

Because his stardom lasted for decades – and his pursuits ranged from films and festivals to conservation – there was a different Redford for everyone. His projects were popular without pandering, serious without scolding. They assumed that sophisticated stories could still go mainstream if they were told well.

Moreover, Redford treated stardom like capital. He invested it, he allowed the returns to compound, and he shared them with the public.

The Sundance festival made this public spiritedness visible. What began as a mountain refuge became a platform, and then an economy. For filmmakers, it presented opportunities to hold premieres, find buyers, and build careers. For Utah, it meant jobs, tourism, and pride. For audiences, it reimagined what movies could be. The same institution pleased progressives (for raising up new voices), reassured moderates (for its entrepreneurship), and appealed to conservatives (through its respect for work and local prestige).

Even as Sundance later faced criticism for becoming commercialized, Redford’s vision endured, because the festival still produced access, jobs, and opportunities for entire communities. These outcomes proved that he had built an institution resilient enough to outlast him.

Redford managed to give back while still pursuing his own interests. Sundance advanced a vision of cinema that he loved. His conservation efforts protected landscapes he cherished and reflected a Western identity he wore with pride. His projects served him and the public at once, becoming institutions sustained by multiple constituencies.

Not everyone can run that play. Redford’s innate abilities mattered. His global fame supplied leverage when patience and money were required. But what defined him was not only his unique talent. It was his choice of how to use it.

Redford took what was singularly his – talent, beauty, fame – and transformed it into institutions that served everyone else. Just as he built Sundance and advanced conservation, he used his public standing to speak out for democracy, raising alarms about threats to truth, free speech, the press, and the rule of law.

How many other privileged, famous, powerful Americans today will be remembered for doing the same? Redford showed that true American greatness lies not in what you possess, but in what you provide.