Copyright New York Magazine

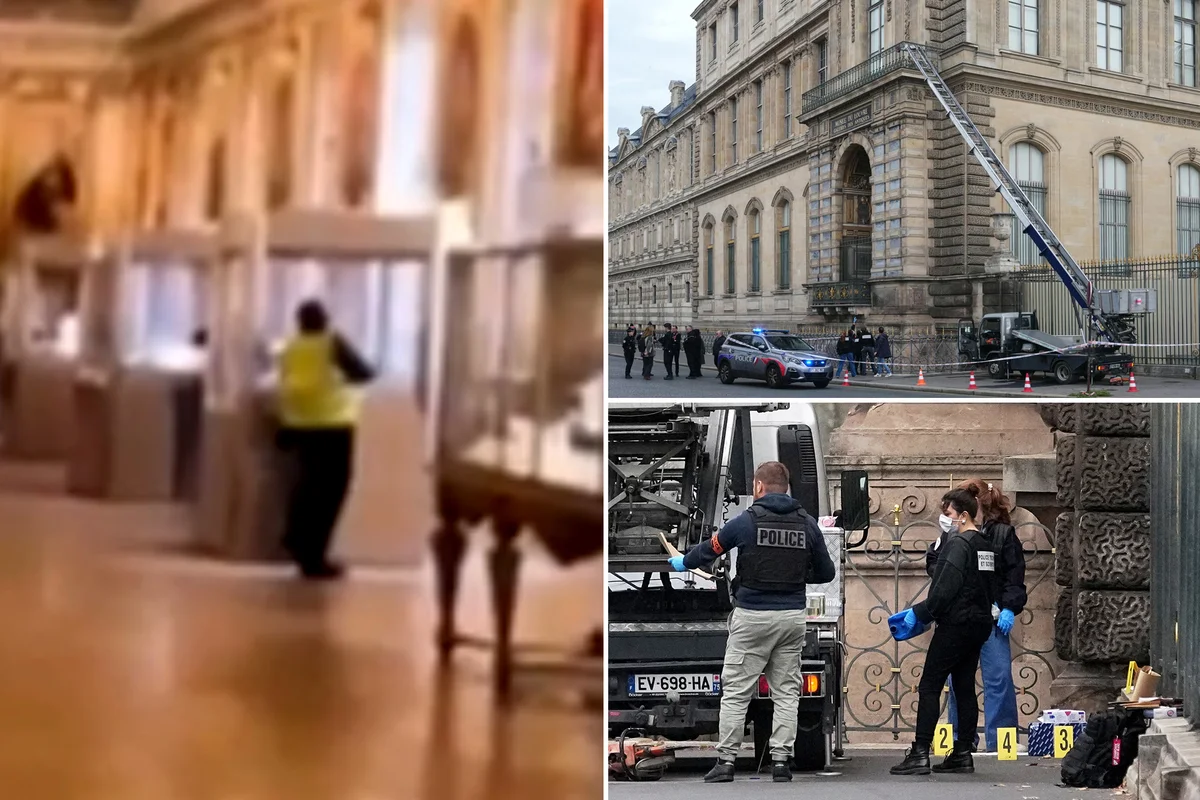

“People may imagine there’s some mastermind, Bond villain–type waiting to receive these things,” James Ratcliffe, director of recoveries and general counsel at the Art Loss Register, told ARTnews. The Art Loss Register, which searches for, records, and helps recover looted or stolen works of art, says otherwise. “History has taught us that there’s no mastermind villain out there,” Ratcliffe said, adding, “This is a case of risk and reward.” The thieves, he said, were likely opportunists rather than specialists, emboldened by old security systems and a clear, high-value target. “It’s not necessarily difficult to get into historic institutions like the Louvre,” Ratcliffe said, noting that museums built for grandeur rather than defense are often difficult to secure. Robert Wittman, who runs a security and recovery consulting firm and helped found the FBI’s rapid-deployment Art Crime Team, said the real work starts after the heist—but added that the crooks may not be up for it. “When I first heard about the theft, I thought, ‘Wow, this is really a professional job. These guys are good,’” he said. “But the more we’ve learned, the less I think that. They left a lot of forensic evidence behind, and that’s one of the cardinal rules of a criminal—not to leave evidence.” … Wittman added that the reliance on brute force and carelessness suggested they were “better at theft than business,” emphasizing that “the real art in art theft is selling, not stealing.” [French interior minister Laurent] Nuñez said that police patrols, which focus mostly on the Louvre’s crowded central entrance, were not near the thieves’ truck. And while the museum is surrounded by cameras, he said there were not enough officers to continuously monitor the feeds. Vernon Rapley, a museum security consultant, said that institutions adjacent to streets they do not control, like the Louvre, rely more on quick police reaction. Labor unions at the Louvre said they had warned that continual renovations, repair work and scaffolding for fund-raising events done on or around the museum made it hard for employees to spot suspicious behavior. “The more we have exterior people working around the Louvre, the harder it is to differentiate who should be there,” said Julien Dunoyer, a leader with the Louvre unit of the SUD union, who has worked as a security agent there for 21 years. On Monday, parts of an unfinished report on the museum by France’s national auditor that had been ordered before the theft were leaked to French news outlets. The auditor found that 75 percent of the Louvre’s Richelieu wing had not been covered by video surveillance and that a third of the rooms in the Denon wing had no surveillance cameras. That wing is where the burglars struck, although officials said that the refurbished gallery they targeted did have cameras. The report also criticized delays in updating the museum’s security system. The burglars’ decision to conduct the heist at 9:30 a.m. local time—right after the museum opened its doors—left museum security juggling competing demands: the evacuation of a large crowd and the need to protect works. Paris prosecutor Laure Beccuau questioned whether guards could tell the alarm was coming from the Galerie d’Apollon as they scrambled to protect visitors from the thieves who were wielding their grinders like weapons. “Perhaps due to emotion and the responsibility they had to ensure the safety of people, they did not hear this alarm,” she said. The culture ministry said five security guards immediately responded to the break-in, following a security protocol that prioritizes visitor safety. Keeping crowds safe at the Louvre, which was targeted in a 2017 machete attack, became increasingly complex as attendance grew during the prepandemic era, reaching 10.2 million visitors in 2018. Since then, the museum has imposed a daily cap of 30,000 visitors, resulting in 8.7 million visitors last year. Experts who observe trends in international art crime [see the heist as] the latest in a series of smash-and-grab thefts focused more on the material value of precious stones or metals than the artifacts’ significance, continuing a pattern that has emerged over the last decade in Germany, Britain and the US. The location, they suggest, would have been of secondary concern to the criminals. “You may ask why thieves who want to steal expensive jewellery are breaking into a world-famous museum rather than a Cartier store,” said Christopher A Marinello, a leading expert in the recovery of stolen works of art. “The answer is simple: it’s because these days a Cartier store is better protected.” A spate of violent jewellery shop thefts mean that many outlets have beefed up their security in recent years, with armed guards on their premises and wares no longer kept on display overnight. Museums, meanwhile, look more exposed, partly because of the in-built reason of being public-facing institutions in historic buildings, and partly the current economic climate in many western countries. “Since Covid, governments across the globe have cut back on law enforcement and the culture sector,” said Marinello. “If thieves can get into the Louvre, it shows how vulnerable our institutions have become. This is a horrible time to be a museum.” With fewer banks to rob and less money held in shop registers, those who like to do their thieving in the real world have been turning to newly loaded cryptocurrency entrepreneurs or looking for easily lifted items like top-end watches. Art exhibits now find themselves at the more rarefied end of this unpleasant business. This will only add to the misery of small museums, three out of five of whom say they’re worried about their future as footfall declines and costs rise. How can they fund extra security in that environment? What makes the Louvre a “slap in the face” for all museums, as art detective Christopher Marinello puts it, is that if it can happen to the the grand old lady of such establishments, what hope do others have. It has already been slated to receive a lavish €800 million makeover. The less exalted won’t be so lucky. For a nation whose character is defined by proud displays of history and culture, the incident is being seen in some quarters as a national humiliation. French President Emmanuel Macron called it “an attack on a heritage that we cherish because it is our history.” He vowed to “recover the works and the perpetrators will be brought to justice,” adding that “everything is being done, everywhere, to achieve this.” The Culture and Interior ministries held an emergency meeting Monday and agreed to ask senior officials across France “to immediately assess the existing security measures already in place around cultural institutions, and to strengthen them if necessary,” the Interior Ministry said, according to Reuters. Justice Minister Gerard Darmanin said the heist gave a “negative” and “deplorable” image of France. “What is certain is that we failed,” he told the radio station France Inter. “The French people all feel like they’ve been robbed.” This theft committed in the world’s most famous museum has caused a profound sense of shock in our country and around the world, much like the 2019 fire at Notre-Dame Cathedral. But, unlike the fire, which led to an incredible wave of support and reconstruction effort, I fear that yesterday’s theft may be irreparable. The Louvre has experienced several thefts in the past, but this one is both the most spectacular and the most serious. It even surpasses the theft of the Mona Lisa in 1911, because, beyond the fact that Leonardo da Vinci’s painting was recovered two years later, the Mona Lisa did not have the same fame at the time as it does today. The items stolen on Sunday carry a much greater symbolic value.