Copyright independent

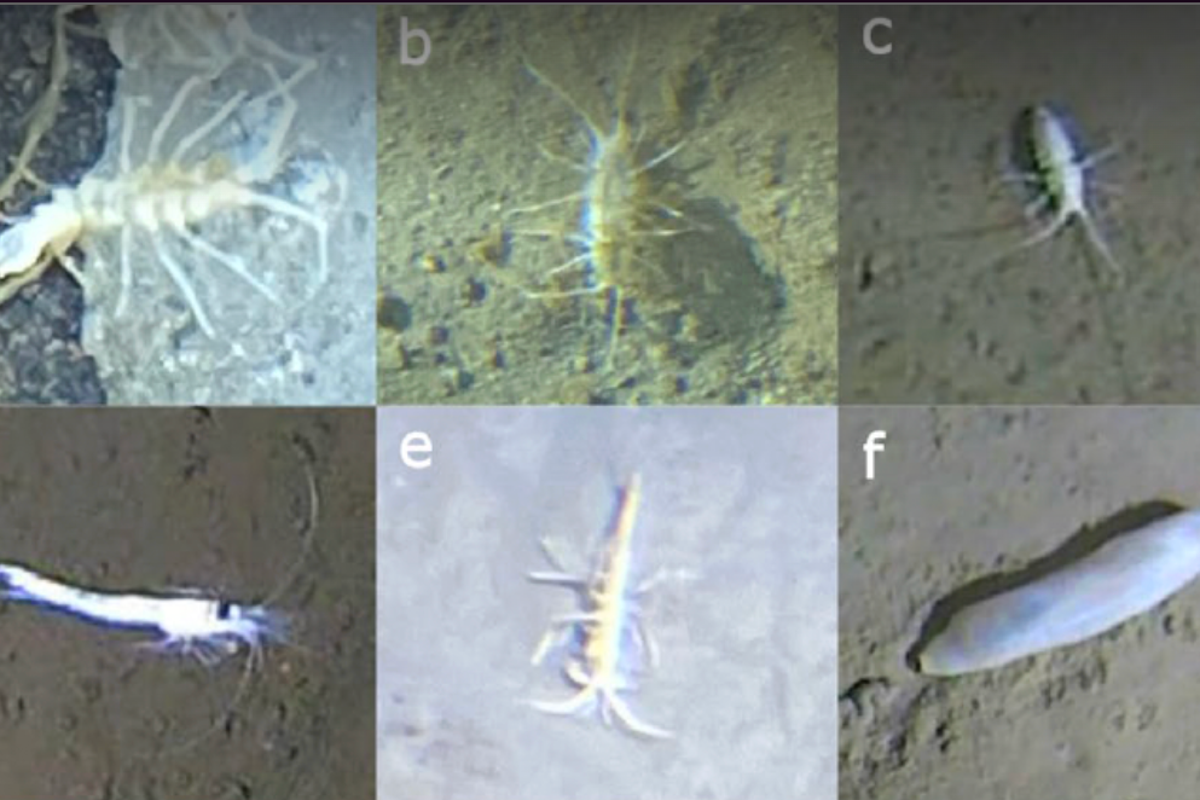

Deep-sea creatures in the trenches of Japan’s volcanically active "Ring of Fire" belt are rapidly adapting to immense depths, scientists found. Researchers documented nearly 30,000 of such organisms, especially those living between 7,000 to 10,000m (22,700 to 32,000ft) below the sea. Their findings revealed that seafloor ecosystems are shaped by depth, food supply, seismic activity, as well as the seafloor's structure. These observations were part of a crewed submersible mission to the hadal zone, the deepest part of the world’s oceans, in the Japan, Ryukyu, and Izu-Ogasawara trenches of the Northwest Pacific Ocean during six submersible dives from August to September 2022. Videos taken by the crew led to the documentation of organisms that spanned 70 morphological groups in 11 taxonomic categories across eight habitat types. For instance, the nutrient-rich Japan Trench, which runs parallel to the east coast of Japan for more than 600km (372 miles), supported high abundances of sea cucumbers and other creatures that feed on seafloor deposits like mysid shrimp and tube anemones at about 7.5km (24,600ft) depth. On the other hand, the more food-limited Ryukyu Trench at this depth was dominated by very different communities with sea cucumbers nearly absent. And in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench, at a depth of about 9km (30,000ft), extensive sea lily meadows were discovered. “This provided one of the most detailed observations of seafloor biodiversity and habitats at these depths,” said University of Western Australia’s Denise Swanborn, lead author of the study published in the Journal of Biogeography. “We found differences in community composition and diversity between trenches, linked to depth and nutrient input from surface waters,” Dr Swanborn said. One of the dives also led to the discovery of the world’s deepest fish, a snailfish living over 8km below the sea level, a finding researchers announced in 2023. The dives revealed that although the abundance of organisms could be lower in the hadal zone compared to shallower waters near the shore, many major groups of animals were still present, displaying “an amazing range of adaptations”, according to Dr Swanborn. “Within trenches, at the same depth band, differences in historical seismic disturbance and seafloor stability created different communities,” the deep-sea ecologist said. “For example, historically seismically active areas in the Japan Trench were dominated by low-diversity organisms that had adapted to their environment, while the more stable under-riding slope supported more diverse communities,” she explained. These findings shed more light on how the depth, regional setting, and seafloor disturbance via seismic activities and nutrient supply from land interact to structure marine ecosystems. Researchers hope the study could provide the foundation for future ecological research in the “deepest parts of the ocean”.