Copyright Arizona Capitol Times

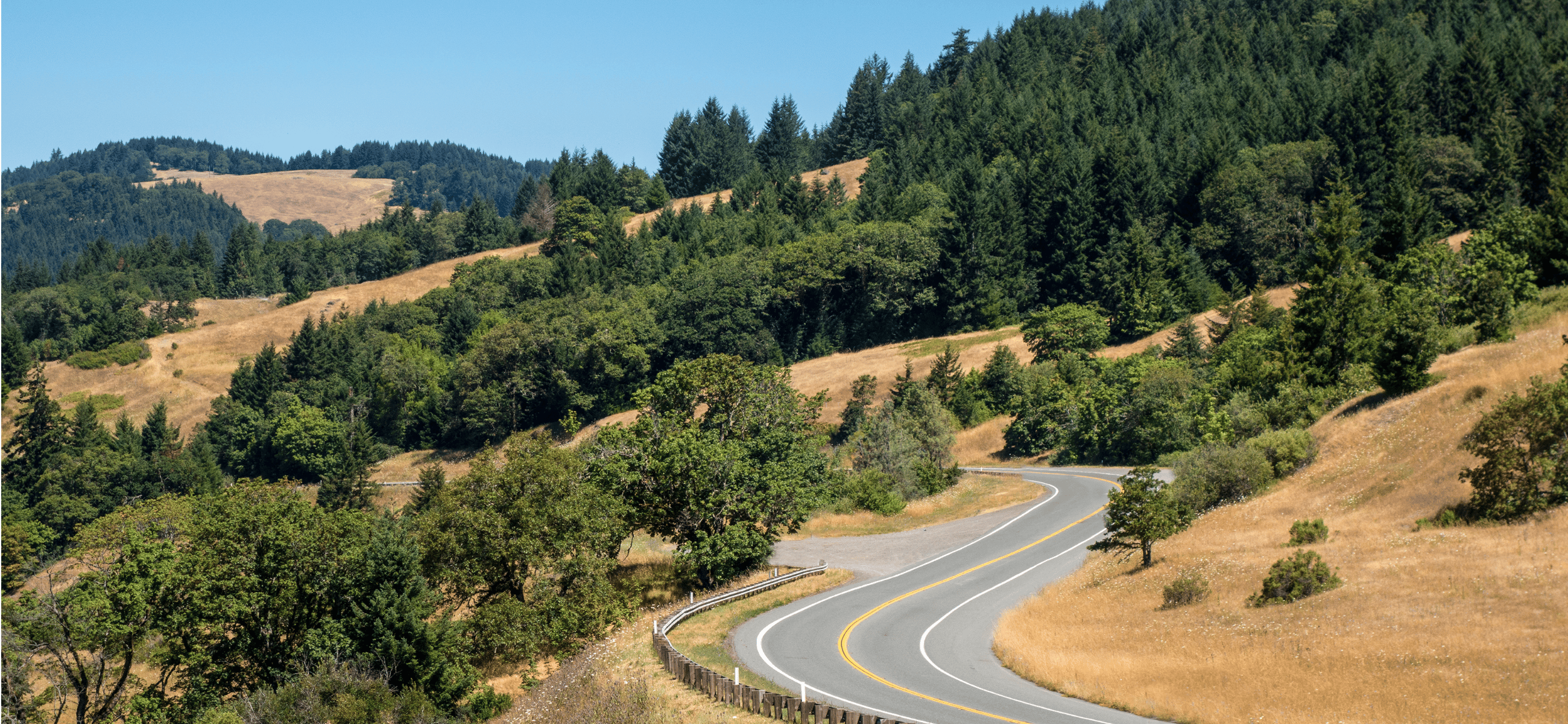

Key Points Prop 50 passed in California, approving legislatively drawn congressional maps through 2030 Rural counties opposed the measure, revealing a sharp coastal-inland divide Critics warn the new maps could reduce rural and Republican representation The passage of Proposition 50 has laid bare long-standing, and perhaps deepening, regional rifts in California’s political landscape according to academics and political scientists in the state. While Prop 50 passed with relative ease, the voting patterns underwriting its victory reveal a fractured political geography. “There are large parts of the state’s geography that voted no on Proposition 50, and they are at risk of losing representation in Congress,” Mark Baldassare, survey director of the Public Policy Institute of California, told State Affairs. “Large parts of the state are going to feel like they don’t have representative democracy working for them because the voters in the more populous areas of the state have decided to make changes in the district boundaries.” Proposition 50, approved by voters in a special election last week, temporarily suspends California’s independent redistricting commission and authorizes the use of new, legislatively drawn congressional district maps through the 2030 elections. The measure, proposed by Gov. Gavin Newsom and the state Legislature, was a response to a Republican-led redistricting effort in Texas. Its stated goal: to shift up to five congressional seats toward the Democrats. Although political divides in California are often framed as urban-rural (code for Democrat-Republican) Baldassare argues that’s an oversimplification. The political terrain, he says, is more textured. He suggests the state can be broadly divided into three regions: coastal, Central Valley and mountain constituencies. “The coastal vote, which is largely Democratic and represented by Democrats, is one category. Then the central vote, which is largely the Central Valley … and then there are the mountains, particularly the northeastern part of the state.” It’s this northeastern corner that has emerged as California’s political outlier. Counties like Modoc, Shasta and Lassen posted some of the state’s highest “no” votes. Henry Brady, a professor of political science and public policy at the University of California at Berkeley, attributes that resistance to both geography and a persistent sense of exclusion. “That part of the state has always felt cut off from the rest of California,” he said. “First of all, it’s 500 miles from any really nearby urban area. Second, it feels like the policies followed by the state are much more oriented toward the cities and the coast than toward the agricultural farmlands in places like Modoc.” The region has long harbored secessionist ambitions. Since 2013, a fringe movement called the State of Jefferson, envisioning a breakaway state formed with parts of southern Oregon, has tapped into a feeling of political disconnect. “These are very small counties in terms of population, so they ultimately don’t have a big input in terms of political power,” Brady said. “And a lot of people in California know nothing about them, they’ve never been there.” He added, “There’s been a long-standing, not, I don’t think, serious, but nevertheless extant, movement to separate themselves from California. So this would not be the kind of thing they would support.” While the northeast is both geographically and politically remote, other voting patterns around Prop 50 defied easy classification. Most notably, southern counties like Riverside and San Bernardino, historically conservative inland counties, swung toward “yes.” Brady attributes this to demographic shifts: a growing Hispanic population that trends more Democratic and was, in his words, “not happy with Mr. Trump.” Even in the Central Valley, long seen as a conservative stronghold, results were mixed. “The voting between the two groups in counties like Fresno are much closer,” noted Blake Zante of the nonpartisan Maddy Institute based in the San JoaquinValley. “The current separation is about 100 votes between ‘yes’ and ‘no.’” Deep pockets of Republican opposition remain throughout the Central Valley, particularly in Kern, Tulare and Kings counties. Brady describes these areas as dominated by “older white landowners.” Kern County, home to former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, is often dubbed “Texas in California” due to its oil and gas industries and staunch conservatism. “That’s a very, very conservative part of the state,” Brady said. “They’re Republicans.” The implications of Prop 50 are significant for how the state’s citizens are represented — or not — by their elected officials. While Republicans make up 25% of California’s registered voters, they may soon hold as little as 10% of the state’s congressional seats. “That’s particularly problematic for those one in four Californians who are Republicans,” Baldassare said. “It leads to feelings of political alienation and underrepresentation.” Brady agreed, lamenting the decline of moderate Republican voices in the state. “It would be nice to have a strong Republican Party that once in a while gave us an Arnold Schwarzenegger, for example. We’ve had some darn good Republicans in California over the years.” That sense of marginalization is already prompting political backlash. Just days after the vote, Assemblyman James Gallagher, who represents rural counties north of Sacramento, addressed the Shasta County Board of Supervisors. He called the passage of Prop 50 a “catalyst” to reintroduce a resolution to form a new state that would sever inland California from the coast. While Gallagher’s proposal has little political traction, it underscores the deepening divide between a coast-dominated Legislature and a rural population that increasingly sees itself shut out. Baldassare warned that Prop 50 may only intensify these divisions. “We have a state where, when you drive around, you realize that large geographic areas are in a different frame of mind politically than where most of the population lives, in coastal California.” As the state gears up for the 2026 gubernatorial race, Proposition 50 has done more than redraw maps. It has again spotlighted deep demographic and geographic schisms. “These are real divides in California,” said Baldassare. “The governor had talked about trying to bridge some of these political divisions — but this is not going in that direction.” A review of the Prop 50 vote map shows that many of California’s most geographically expansive regions rejected the measure, and they now stand to lose congressional representation under the newly approved district lines. “And therein lies the challenge for direct democracy in this case,” Baldassare said. “Coming up with something that works for the entire state. But large parts of the state are going to feel like they don’t have representative democracy working for them because the voters in the more populous areas have decided to make changes in the district boundaries. So it’s definitely a challenge.”