By Contributor,Matthew Mayhew

Copyright forbes

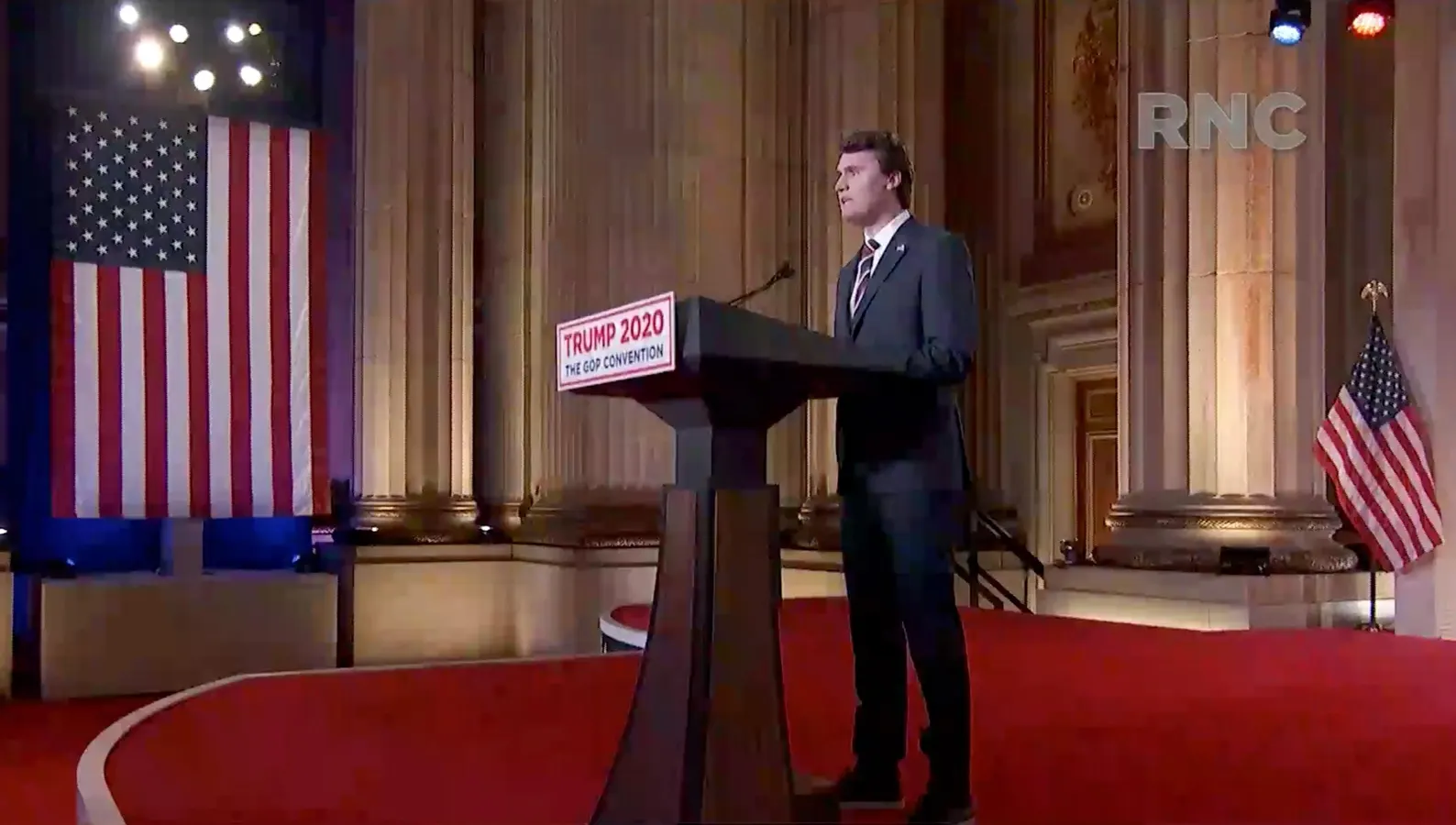

CHARLOTTE, NC – AUGUST 24: (EDITORIAL USE ONLY) In this screenshot from the RNC’s livestream of the 2020 Republican National Convention, Charlie Kirk, founder of Turning Point USA, addresses the virtual convention on August 24, 2020. The convention is being held virtually due to the coronavirus pandemic but will include speeches from various locations including Charlotte, North Carolina and Washington, DC. (Photo Courtesy of the Committee on Arrangements for the 2020 Republican National Committee via Getty Images)

Photo Courtesy of the Committee on Arrangements for the 2020 Republican National Committee

The country stands at a political crossroads, and nothing brings that into sharper focus than the recent, tragic assassination of Charlie Kirk at Utah Valley University. An act of political violence on a college campus, it stands as a grim testament to the escalating polarization that has seeped into every corner of public life—including the hallowed halls of academia. This shocking event forces us to examine the nature of our political divisions, and to ask: how do professors’ own politics contribute to, or perhaps help heal, these societal rifts?

Funded by the Templeton Religion Trust, the InForm survey asked nearly 1,000 faculty members about their opinions on matters of university life, including issues relating to political and/ore ideological diversity. Data were weighted to represent national norms across various factors, including region and institutional control. Of the 977 usable responses, faculty respondents were predominantly liberal (50.5%), followed by moderates (30.4%), and a smaller group of conservatives (11.4%).

This political distribution is reflected in demographic and disciplinary differences. Conservatives were overwhelmingly White (92.2%) and Christian (84.2%), while liberals showed greater racial diversity. In terms of tenure, tenured faculty were most common among liberals (44.5%), followed by moderates (35.4%) and conservatives (34.6%). A higher percentage of conservative faculty were not on the tenure track (54.8%) compared to moderates (48.7%) and liberals (38.0%). There were also significant disciplinary variations, with conservatives most concentrated in Business (35.4%) and liberals in Social Science (26.7%), Arts and Humanities (21.3%), and STEM (22.0%). Across all groups, the majority of professors were affiliated with public institutions, with similar percentages for conservatives (63.8%), moderates (67.6%), and liberals (66.0%).

Analyses were performed to identify statistically significant differences between political and ideological diversity items and a professor’s political leanings. Results reported here took a deep dive into these relationships, controlling for several covariates, including rank, gender, race, religion, academic discipline, and institutional control (public vs. private).

This closer examination of the data on professors’ political views reveals a reality more nuanced than the simple ideological battleground portrayed by cable news. Without a doubt, deep points of divergence emerged. Liberal professors are more likely to believe that institutional leadership is genuinely committed to advancing and promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives across racial, religious, gender, and sexuality-based lines. This belief also translates into their classroom behavior; liberal professors are more likely to have taught courses where they have expressed their own political views and where students have also expressed politically liberal views. Furthermore, they are more likely to report their colleagues’ support for all forms of diversity, including political diversity, within their departments. These points suggest a fundamental ideological difference in how liberal professors perceive and interact with the culture and mission of their institutions.

MORE FOR YOU

However, a focus solely on these differences misses a crucial part of the story—the significant common ground that exists across the political spectrum. The data reveal that liberal, moderate, and conservative faculty members are equally likely to have taught courses where students expressed politically conservative views. This shared experience challenges the narrative that only one side is being heard in the classroom. More importantly, it highlights a common goal: faculty from all three political groups agree that institutions should place a greater emphasis on enhancing political diversity on campus.

Perhaps the most salient and hopeful results regarding political diversity among faculty are the points of consensus. While professors may disagree on the specifics of DEI initiatives and the role institutional leadership plays in their prioritization and implementation, they share a common belief that the academic environment would benefit from a broader range of political perspectives. When asked, conservative, moderate, and liberal professors agree that institutions should focus more improving political diversity on campus.

Despite the very real ideological divides, productive dialogue and collaborative action are possible paths to a more vibrant and intellectually diverse campus—one that may not lie in resolving every disagreement, but in building upon the shared understanding that a variety of political viewpoints is essential for a healthy academic community and a functioning democracy.

Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions