The NFL’s 2025 season began with new kickoff rules, a new NFL Players Association executive director, and a new team for Aaron Rodgers.

But one thing remains the same: All players’ injuries will still be reported to the public in detail. When a wide receiver tears his Achilles, the public will have the right to know. When a quarterback is down with Covid-19, that too will be reported.

Advertisement

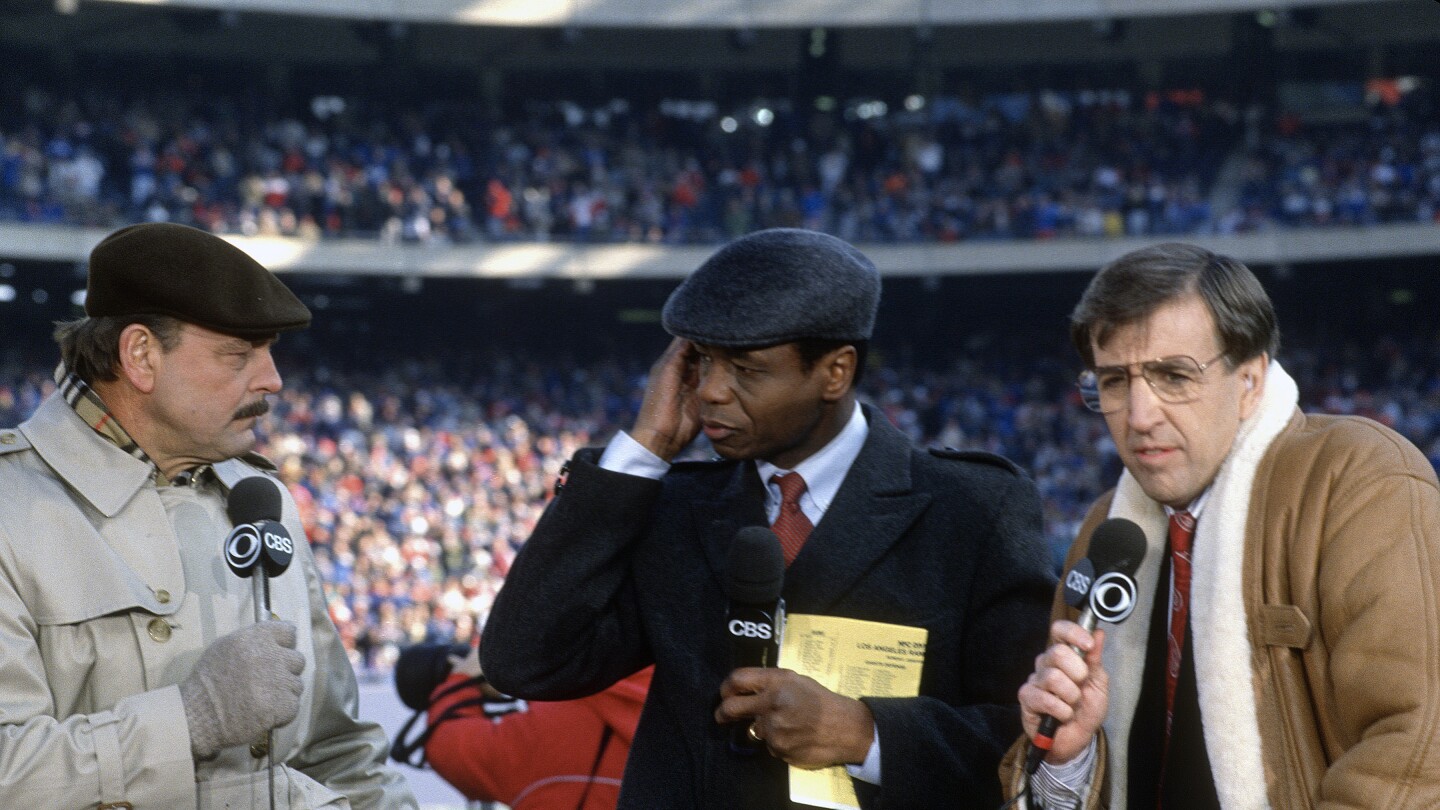

Why has health data — perhaps the most private information in modern society — become so accessible? When it comes to professional athletes, the answer involves sports betting. Since 1947, NFL teams have been required to disclose injuries to “protect the integrity of the league” from gamblers seeking to capitalize on inside information about players’ health. This rule came about after an NFL commissioner discovered a sudden and dramatic shift in betting after a “big” gambler learned that five players on the same team had the flu.

As time went on, these disclosures became unpopular with some players, and many hoped that injury reporting systems would be rendered illegal, especially after the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was adopted. To their disappointment, however, HIPAA effectively exempted team sports from the privacy rule, and professional players are generally required to waive their health privacy rights under their individual contracts and collective bargaining agreements.

Thus, the majority of U.S. sports leagues, including the NBA, MLB, National Women’s Soccer League, and Major League Soccer, currently employ some form of injury reporting system. (NHL teams also regularly disclose information about their players’ injuries, but these disclosures often lack specificity.) This means that athletes are subject to a much higher standard of disclosure than other public figures, including corporate executives or presidential candidates. And with the trend toward professionalization of college sports, it appears that it is only a matter of time until the NCAA adopts the same injury reporting model.

Advertisement

While these disclosures may help to level the playing field when it comes to preventing insider betting, they present significant problems for both players and society at large. From an athlete’s perspective, players on a rival team can use the information to target the athlete’s injured body part. During the most recent NBA playoffs, for example, there were concerns that one player had tried to intentionally hit the injured thumb of an opponent.

In addition, while such reporting policies typically require specificity, they also allow teams to employ a “personal reasons” explanation in situations where a player’s absence results from a more sensitive issue, such as mental health issues or pregnancy. This system, although perhaps well intentioned, may paradoxically draw more attention to an athlete’s absence, fuel public curiosity, and invade an athlete’s privacy even further. In fact, such a “personal reasons” designation recently triggered speculation that Rickea Jackson, a WNBA player, was pregnant. (She was not.)

The use of the “personal reasons” designation may also perpetuate stigmas and stereotypes. Indeed, treating mental health issues as “personal reasons” may imply that mental health issues are not as “real” as physical injuries or are shameful. After all, there is a long history of people hiding mental illness out of fear of ostracization. Thus, the “personal reasons” designation in situations involving mental health can inadvertently fuel the very stigma it was designed to address.

From a societal perspective, these injury reports present additional issues. First, anecdotal evidence suggests that exposure to betting-related data may aggravate compulsive betting. Second, even with strict enforcement, teams today manage to hide their athletes’ injuries, rendering injury reports misleading. For example, in 2018 LeBron James played three games during the NBA Finals with a severely injured hand, all without disclosing the injury. Thus, these reports fail even on their own terms.

Advertisement

So what can be done to address these problems? Sports leagues should do away with injury reports. Instead, these organizations could simply indicate whether an athlete will be available to play — with no explanation or a reference to a reason. This approach, currently adopted by some college conferences, would provide fans with sufficient information, would avoid complicated dilemmas as to how to report absences due to mental health issues or pregnancies, and would protect athletes’ private health information.

To be sure, our proposed solution is not perfect. It may, for example, result in other forms of privacy invasions by gamblers determined to obtain unfair advantages. But the time has come to recognize that protecting the “integrity of sports” means more than providing bettors with information. It also means protecting the privacy and well-being of fans and athletes.