The truck wheel’s inner tube was right in front of me, no longer half-submerged in the pond’s late summer muck. After so many hot weeks without rain, the water had dried up and the garbage was completely exposed.

My feet barely sank into the mud as I pulled the inner tube free. It was heavier than I expected, full of leftover pond water. I tipped it to drain the water, so I could carry it away. But that water just kept dribbling out.

It was dark and smelled of rotten leaves. As I shook the tube, I tried to keep the muck from getting on my shoes. There must have been three or four gallons of it. Contorted in an uncomfortable crouch and harassed by bugs as the water glugged slowly out of the little hole, I felt impatient. I was ready to share my grubby prize with my friends, but the hole was so small and I was still far from the road. So, I waited, watching the water continue to trickle out.

But I couldn’t just wait. Instead, my mind drifted to catastrophe, and I began imagining a near future where I could no longer take water for granted. Such a thought was in my head not just because I’m prone to binge on dystopian novels but because I read the newspaper and watch the TV news at night. So, there I was, crouching at the no-longer-pond’s edge, cradling that huge inner tube, and wondering how long it would be in our overheating future before the dark, fetid water I was pouring onto the ground would seem like a precious resource for my family and me. Extended drought? The collapse of our water infrastructure? War? None of those nightmare scenarios is remote enough anymore that I can simply dismiss them as figments of my overactive imagination.

Meanwhile, I continued to think about that gross water. How would I clean it if I needed to? I recalled my survival-skills training between 8th and 9th grade and decided I would first have to filter it, then boil it, and finally treat it with iodine. And no, it wouldn’t be delicious or refreshing, but it probably wouldn’t kill us either. Then I thought about how it might have been inside that inner tube for years and realized that life would have to be brutish indeed before I considered such a last resort water source.

Is our water infrastructure here in New London, Connecticut, old? It sure is. Sometimes there are even black flecks in the water that pours out of our faucets. But no worries now. After all, I had a big bottle of fleckless water in my backpack, and I certainly wouldn’t need to drink that ancient inner-tube pond water. Not today, anyway.

Better yet, rain was forecast for later in the weekend! And so, the moment passed — but not completely because I suddenly remembered some water I drank 30 years ago that had been boiled over a wood fire in a small town in Guatemala when I was part of a peace delegation there. All these years later, my tongue could still feel the eerie dryness, the woodiness of that water, and suddenly I wondered whether that feeling would be in my future, too.

Water Wars — For Real

The kids in New London had gathered in this park just a few weeks earlier for “Water Wars,” a beloved community institution where, on a hot summer morning, kids and grown-ups arm themselves with water guns and soak one another. That day, there was also a dunk tank, a deejay, and dozens of people running around with big, brightly colored Super Soakers.

In truth, I’ve never liked the event, perhaps because I’m a grumpy old person who just doesn’t care for guns of any sort, even play ones. And now, contemplating the future loss of water and the violence that could come with it, those Water Wars suddenly seemed like fin de siècle madness to me. As I — excuse the image — immerse myself ever more deeply in the current and impending water crises, I find myself increasingly troubled by the very real water wars to come.

The Pacific Institute, which has tracked water-related conflicts for three decades, never counted more of them than the 347 in 2023 (the last year for which it had complete data). Its report distinguished between water as a trigger for war, a weapon of war, and a casualty of war. In Burkina Faso, Mexico, Ukraine, and elsewhere globally, civilians now all too often find themselves going without water, as its sources and treatment facilities are destroyed, while groups fight over who controls what water remains.

Dr. Peter Gleick, cofounder of the Pacific Institute, wrote The Third Age of Water in which he argues that everyone deserves the “human right to water.” And at this moment, nowhere on earth is water more a cause for and casualty of war than in Palestine. As he notes, that is “partly a reflection on the scarcity of water in the region. It’s partly a reflection on disputes over control of land in the West Bank. And it’s partly a reflection of the massive destruction of Gaza after the Hamas attack in October, where infrastructure of all kinds has been targeted — civilian infrastructure, schools, hospitals, water systems, energy systems. It’s a reflection of the broad violence in the region.” In short, there is no longer any human right to water in Gaza or parts of the West Bank either.

And believe it or not, even as such realities came to my mind, the water was still dribbling out of that inner tube, while my arms hurt ever more from holding it up. Still, when I placed my minuscule discomfort alongside that of all those people in Gaza, waiting in vain for both water and food in a manmade famine of genocidal proportions, I felt ashamed.

All Wars Are Resource Wars

Even before the complete leveling of all infrastructure there in an almost two-year massive bombardment, the lives of Palestinians were violently controlled and curtailed by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF). An IDF Military Order had long forbidden Palestinians from building any new water installations without a permit from the Israeli army. Since that order was issued in 1967, almost no one has gotten such a permit. So, Palestinians weren’t able to drill new water wells, install pumps, or even deepen existing wells. And now, many of them don’t have access to fresh water springs at all and are cut off from the Jordan River.

In a Big Brother twist that boggles the mind, they aren’t even allowed to collect rainwater in cisterns. As writer Ta-Nehisi Coates observed in his book The Message, “Israel had advanced beyond the Jim Crow South and segregated not just the pools and fountains but the water itself.” And if anyone is still on the fence about that one-sided war of dominion, such a piece of information should knock you to the side of the suffering, starving, thirsty, dying Palestinians.

Of course, on some level, all wars are resource wars. Military scholar Michael Klare made exactly that point as early as 2001. For nearly two years, Israel has used Hamas’s brutal October 7, 2023, attack on civilian and military targets as its excuse to destroy as much of Gaza as possible — mission (almost) complete. Trump’s “Riviera of the Middle East” fever dream of Gaza as a casino-state built to Atlantic City levels of gaudiness might never be realized, but Israel’s long game certainly includes complete control over Palestinian natural resources, including oil and gas. Americans are propagandized to think of the “poor Palestinians” (if we think of them at all), even though Palestine is rich in natural resources.

Trump Doesn’t Drink Water

The rumor is that Donald Trump drinks 12 Diet Cokes a day (the best argument against “Just for the Taste of It” I’ve ever heard). His aversion to drinking water is well known; and his antipathy toward the basic building blocks of life seems to come right out of a Mad Max movie, but it’s consistent with his administration’s assault on the water system infrastructure in the United States.

The 2024 Report Card of the American Society of Civil Engineers gives our water infrastructure a C-. Worse yet, they project a $309 billion chasm in funding between the drinking-water-infrastructure needs of this country and what the federal government is allocating in investments. And that chasm is expected to grow into a gulf of $620 billion by 2043. In short, we’re losing the equivalent of 50 million Olympic-sized swimming pools of water through leaks and cracks every year, more than enough to meet the needs of the 2.2 million Americans who don’t have running water or basic indoor plumbing, according to Dig Deep, a water access organization. That’s one hell of a lot of people in the richest nation on earth, even if not that many in a population of 340 million.

While you might imagine that it’s just back-to-the-landers and old White hippies who like to chop wood and haul water, more than 44 million of us are served by inadequate water systems that recently had Safe Drinking Water Act violations — one of every seven Americans. My black-flecked water might be among that number.

President Trump, of course, is hardly bending over backwards to address such a gulf in water access. For him, undoubtedly, the problem doesn’t even register, not like railing against apocalyptic city hellscapes, deputizing brutes to muscle immigrants out of the country, or selectively mourning some victims of gun violence and not others.

Rain Barrel Resistance

I collect rainwater in three big olive barrels with spigots drilled into the bottom and mesh stretched over the top to try to keep mosquitoes from setting up residence there. Earlier this year, I even bought a dozen goldfish after the Internet assured me they would eat mosquito larvae. I freed them into those barrels and encouraged my kids to name them. Within a week, unfortunately, they turned up dead at the top of the barrels.

I use the water to keep my weedy garden alive and give it to my chickens (assumedly with tasty mosquito larvae for extra protein). I got the rain barrels after reading that unchlorinated, untreated rainwater is better for plants. In light of everything, can I now see those barrels as an act of resistance on this distinctly overheating planet of ours? How long before someone tries to regulate rainwater collection? How long before the tech bros figure out a way to put a price tag on what falls from the sky? (That’s anything but far-fetched if you consider how everything else is being privatized.)

How long can I depend on the relatively clean water from my tap? It flows in a big underground pipe from a reservoir less than 10 miles from my home and is filtered by my local water company. That system has provided New London, a town established in the 1600s, with water for a good long time, but will it keep doing so for the foreseeable, ever hotter future? In fact, is there a foreseeable future?

Sometimes, I pay my water bill in person. I asked once if there was anything I could do to be more efficient and steward my water resources better. The woman behind the counter looked at my bill and then said, “For a single person, you’re doing pretty good.”

“Oh,” I replied, “I’m actually a family of five.” (I wondered then if I looked like a single lady or if she was just basing her statement on my water consumption.)

“What!?” she exclaimed and added, “You are not a very good water customer then. You should get a pool or wash your car more or something!”

I realized that she was joking and we laughed together. Then, she commended me on my family’s good water savings.

And it’s true that here in the northeast, I might still be able to lull myself into complacency. It’s raining, in fact, as I write this. But I can’t act so naively when we’re clearly heading off a weather cliff. A recent headline in my local newspaper still haunts me. “Scientists tap ‘secret’ fresh water under the ocean, raising hopes for a thirsty world.” What could go wrong? After all, there’s evidently a vast freshwater aquifer beneath the ocean floor off the eastern coast of the United States and, amid a massive and growing water crisis, the world needs water. However, Woods Hole geophysicist Rob Evans offers caution: “If we were to go out and start pumping these waters, there would almost certainly be unforeseen consequences.”

Will that aquifer and others like it become the United States’ strategic reserves, alongside oil reserves and the nuclear weapons we keep in “reserve” to protect our wealth? Might countries like ours someday go to war to defend any edge they might have in dwindling water reserves? Trump’s saber-rattling at our neighbor to the north was at least partially water-related, wasn’t it? In his usual fantasy-filled fashion, he imagined a “large faucet” directing Canadian water to California’s needy orchards and fields.

Preparing for — Responding to — All the Bads

Which will get us first? Forest fires or fascism? Misogyny or microplastics? Global warming or the paramilitary/ICE take over? Obviously, we’re in an age of polycrisis, of multi-headed, interconnected catastrophes that we need to confront all at once.

Talk about drinking from a fire hose! But at least we have to keep trying.

I suffer from brief spells of wanting to just sink into the leftover muck in the park where I found that old inner tube and let all the change — the good and bad, but mostly the bad — just wash over me.

Instead, I shouldered that still heavy (but by now empty) inner tube, put one small foot in front of another, and hauled it out of the pond bed. As I dragged it along the path, I toggled between despair, hopelessness, and a steadfast grind of resolute, teeth-gritting effort to do good.

I can’t change the gutting of federal institutions or the assault on science. But I can pick up trash in a public park. I can’t end the Israel Defense Forces assault on Gaza, but I do boycott (no SodaStream for me). I have divested (my paltry nest egg) and I still support sanctions.

I can’t keep Donald Trump from building up ICE as a paramilitary goon squad or stop the polar ice caps from melting, but I can smile at my neighbors, network with friends into rapid response whenever ICE shows up, and do my best not to use too much water.

It’s all so small, given everything we face, that it’s almost not worth mentioning. Still, that drying pond bed is at least a little cleaner, my community a little friendlier, and I am at least witnessing (and trying to alleviate) the suffering in Palestine. Shouldn’t that matter at least a little?

Copyright 2025 Frida Berrigan

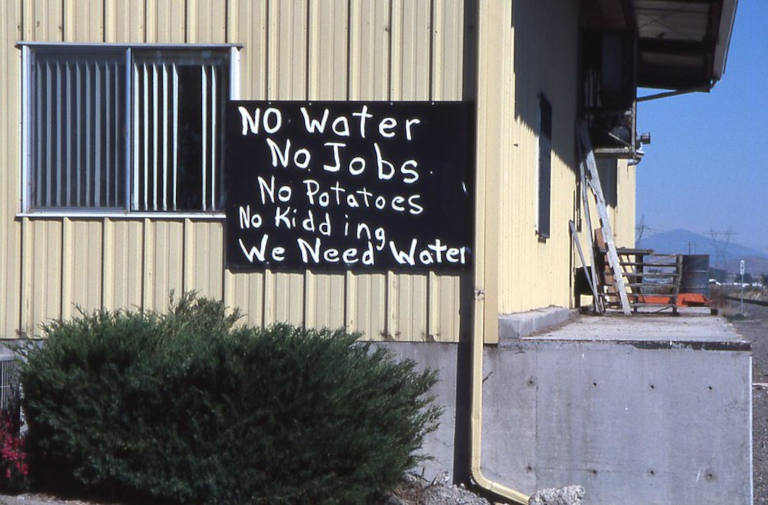

Featured image: Drought by Oregon Department of Agriculture is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 / Flickr