It’s become known colloquially as the “Baby Boom,” the period after World War II that saw a dramatic rise in the birth rate in the United States. Between 1946 and 1964, more than 78 million Americans were born.

But this procreational uptick had an unanticipated outcome in Virginia in the decade that followed: There weren’t enough elementary school teachers to meet the demand of the flood of students enrolling in their classes.

Pupil enrollment in 1953 grew by 27,000 in the 1953-54 school year. To meet that level of enrollment, the state needed an additional 3,500 teachers, but the rate of new teachers being certified in the state, up to that point, was well below that number.

An article in the May 17, 1953, Times-Dispatch states, “The picture is brief and frightening. Each year, 1,500 teachers quit teaching in Virginia. Each year, 1,000 new teachers are needed to keep up with increased births. That makes 2,500 additional teachers needed each year.”

The Virginia Education Association a saw a troubling scenario, observing that 1951 saw the most births in Virginia’s history up to that point, at 86,771. And the state was already struggling with the school population as it stood.

“By 1963, its officials figure, the school population will have approached or passed the 1,000,000 mark, whereas they find no promise in the immediate program that the supply of teachers will keep pace,” reads an article in the Jan. 25, 1953, Times-Dispatch.

That same article likewise stated that while the underlying reason for the surge in the postwar birth rate wasn’t clear, “the stork has had pretty much of a field day.”

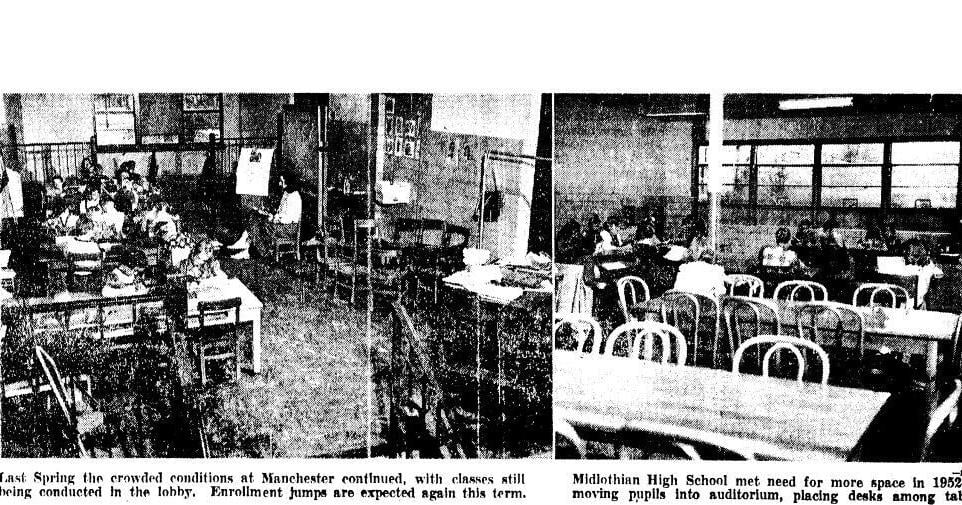

A study from the state’s department of education found that more than 63% of teachers were teaching more than 30 students. And 59 teachers in the state were teaching classes with 60 students.

During the 1952-53 school year, 270 teachers in 17 counties and 10 cities had resorted to teaching in two separate shifts in order to accommodate the number of students.

Additionally, the most dire shortages were typically in more rural areas of the state, particularly because the salaries were generally lower than in urban areas.

Lindley J. Stiles, dean of education at the University of Virginia, pinpointed low salaries as one of the biggest obstacles to being able to attract the number of new teachers needed in the state.

“It will be impossible to establish general respect for the teaching profession as long as our teachers are inadequately paid,” he said. “Many who have been aided through college by scholarships later leave the profession when they find that teachers’ salaries are inadequate.”

By fall of 1953, the state had come up with a number of different potential solutions for addressing the shortage. The first was a $1,400 scholarship for college students seeking to take up teaching after graduation.

The second was a pay raise for teachers, which became the subject of debate in the next General Assembly session. And the third was the formation of a state committee to run a campaign to find and hire more teachers.

Newly elected Gov. Thomas B. Stanley advocated for teachers’ salaries to be increased in his inaugural address, though at a more moderate scale than recommended by the VEA. By the end of 1954, all counties in Virginia adopted a rise in pay scale for teachers, with a minimum starting salary rising to $2,100.

The ultimate goal, as endorsed by Stanley, was a scale of $2,400 minimum to $3,600 maximum, to be reached in four years with more than $5 million appropriated by the General Assembly in order to fund the raises.

Even before the raises went into effect, however, the number of newly certified teachers was beginning to catch up with the demand, and the number of teachers taking on double shifts was already on the decline.

By the end of the 1950s, the state had finally, mostly, caught up. A report in the Aug. 27, 1959, Times-Dispatch noted that there was a net gain of more than 1,000 qualified teachers between the 1958 and 1959 school years, and that the gap between the number of needed replacement teachers and newly certified teachers was narrowed to just 39.