Copyright thespinoff

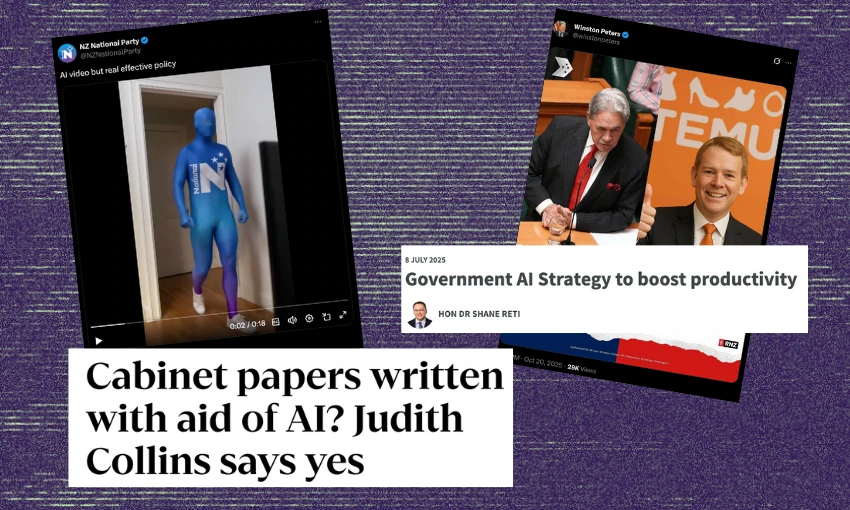

It’s increasingly part of everyday life for many of us, and our elected members are no different. But are there laws in place if things go wrong? In the video, a teenager is playing on a PlayStation next to a cartoon figure with the “Labour” logo on its chest. A humanoid character wearing what looks like a lycra suit emblazoned with the National logo walks in and turns off the game. “I’ll get a job now,” says the teenager, getting up. The video, posted on National’s X account, was intended to highlight National’s policy of not allowing 18- and 19-year-olds to claim Jobseeker benefits if their parents earn over $65,000 a year. It was also AI generated, captioned “AI video but real effective policy”. Numerous commenters pointed out that using AI to make the video meant that a teenager didn’t get a job performing in the ad. From AI-generated social media posts like Winston Peters’ “Temu Hipkins”, Act using an AI-generated image of a “happy Māori couple” and Judith Collins using Chat GPT to help write speeches, many politicians are clearly making use of AI, just like everyone else. At times, this has been used to make a point, like Act MP Laura McClure using AI to make a “deepfake” nude picture of herself, to demonstrate how easy it is for artificial intelligence to be used for sexual exploitation. McClure’s member’s bill criminalising such deepfakes has been pulled from the biscuit tin to be debated in parliament. According to the New Zealand AI Forum, 82-87% of businesses and 69% of consumers are using AI for productivity on a regular basis. Indirectly, almost everyone will be encountering AI – features are embedded into Google, the most common search platform, used in RNZ podcasts to reconstruct the voices of the dead, and invisibly used to enhance images in advertisements. And then there are the more harmful uses of AI: in scams and for the purposes of spreading misinformation, not to mention its intensive water and electricity use and its potential to replace human jobs. “There are so many issues around if AI-generated content should be labelled, or whether banks are responsible if a customer is defrauded by an AI deepfake,” says Andrew Lensen, a senior lecturer in AI at Victoria University of Wellington. Despite this, there’s nearly no regulation in New Zealand that specifically deals with AI. “For example, the Bill of Rights prevents discrimination on basis of ethnicity, but AI models may have been trained on data biased towards certain ethnicities,” Lensen says. Similarly, the Official Information Act ensures people can access information about a decision made about them, for example regarding an ACC process. If that decision is made, or partially made, by an AI system that can’t transparently explain what it did and why, the OIA process will be compromised. At the moment, AI in the legal system uses “applications of existing laws in the margins, leaving it up to judges to interpret”, Lensen says. Updating the OIA, Bill of Rights Act, Fair Trading Act, copyright law and other policies to specifically address artificial intelligence would benefit the legal system and the public, says Lensen, who has co-authored an open letter calling for a “a bipartisan effort to produce risk management-based AI regulation and to establish a national AI oversight body”. It’s been signed by more than 500 people, including academics, the co-leaders of the Green Party and members of the public. The best example of AI regulation comes from the EU, Lensen says. “The main idea is different levels of regulation depending on risk.” Mass state surveillance using facial tracking to control where people can go is a huge risk – but many applications of AI are more like summarising articles to answer a question typed into a box, or generating marketing emails. Not without harm or consequence, but less directly so, and often innocuous. While simply copying Europe’s AI law isn’t necessary, the general principle could be used to amend New Zealand legislation, Lensen says. “You don’t want to create more red tape, but where stuff is more risky and at odds with social norms, you need laws to regulate and oversee AI.” Many unions have been opposed to AI, because of its environmental toll and potential threat to workers. Policy is needed here, too. “If companies are replacing workers with AI, should they upskill to new roles? Will we guarantee them beneficiary support as they reskill?” Lensen asks. In surveys, New Zealand ranks as one of the countries with the least trust in AI. But the technology has huge potential benefits, like faster diagnostic imaging in the health sector or making technology more accessible for people with disabilities. “A lot of companies are sheepish about the benefits, because there’s a lack of social trust, and no certainty in the regulatory space,” Lensen says. The government has an “AI strategy” to “boost productivity” and some “responsible AI guidance for businesses” but no clear boundaries on what might happen when something goes wrong. Without careful regulation, an innovative health startup could be rolled out in the New Zealand health system, successfully diagnosing diseases until it turns out it’s not trained on Māori and Pasifika populations, making health inequality worse. Lensen is worried that it will take an egregious, dreadful case of AI harm – child sexual abuse, mass fraud – before AI is regulated. “There are a whole bunch of quite scary outcomes,” he says. For the most part, the National Party hasn’t wanted to touch the issue, taking a “light touch, hands off” approach. “We don’t see a lot of progress, a lot of politicians don’t understand AI and its risks,” Lensen says. But AI videos, images and text generation have clearly already made their way into parliament, and teenage actors and junior speech writers won’t be the only ones affected. “There’s a bit of a ‘she’ll be right’ attitude, without any urgency to do anything about it.”