Copyright Reuters

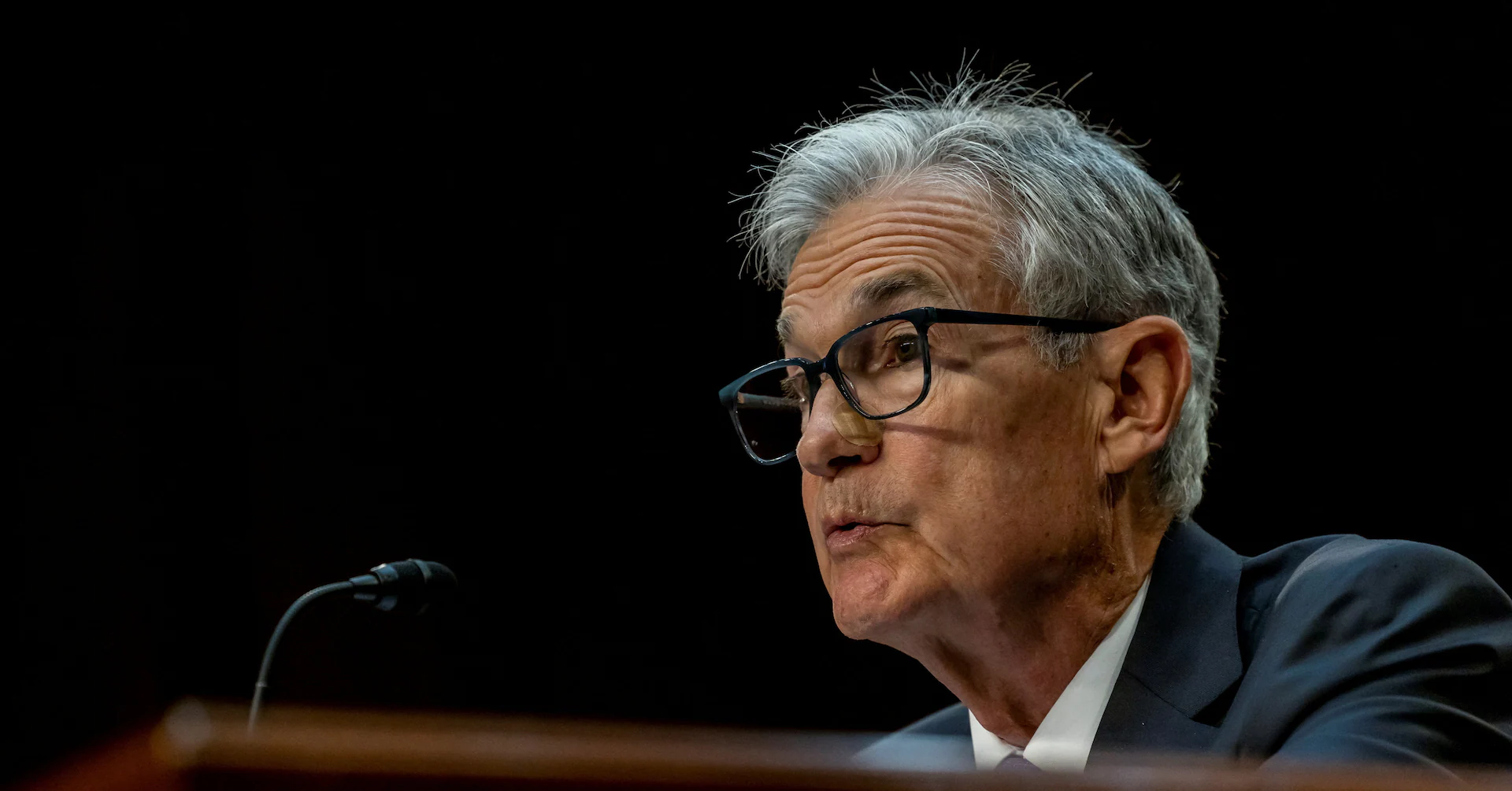

ORLANDO, Florida, Oct 22 (Reuters) - The slide in Treasury yields in the face of record-high stock prices, tight credit spreads, and sticky inflation suggests investors have accepted Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell's steer that policy is being driven by employment, not inflation. So much so, there's a risk that a self-sustaining feedback loop takes hold, whereby labor market concerns depress yields, exacerbating fears that the economy is slowing, which could, in turn, maintain the downward pressure on yields. Sign up here. Investors, starved of official economic data during the three-week-long government shutdown, get one rare bit of guidance on Friday, CPI inflation. The trouble is, it's not the data they want. Friday's report is expected to show that core annual inflation held steady at 3.1% in September. That's more than a percentage point above the Fed's 2% target. Annual core CPI has been 3% or higher almost every month for nearly five years. The bond market is likely to greet this with a shrug. The two-year Treasury yield last week fell to its lowest point since August 2022, reflecting investors' belief that the Fed will cut interest rates again next week, in December, and into next year. The 10-year yield is now below 4.00%, clocking its lowest daily closing level in more than a year on Tuesday. So even if inflation comes in on the firm side, this is unlikely to spark a jump in yields. ASSESSING THE FRAGILE LABOR MARKET With no official economic data in the three-week government shutdown, investors have been filling in the gaps with their own gloomy scenarios. If there's any one thing they've been stewing on, it is the slump in job growth. Although the dramatic drop in job creation has until now mostly been offset by shrinking labor supply, it is alarming. Goldman Sachs economists on Monday outlined five main reasons why job creation was shrinking so rapidly: a slowdown in immigration; reduction in government hiring and funding; adoption of artificial intelligence technology; tariff-related costs and trade uncertainty; and macroeconomic risks. They reckon underlying trend payrolls growth now is just 25,000 a month, some 125,000 per month fewer than their projections in January. It is also well below the "breakeven" pace of job growth needed to stabilize the unemployment rate, which they put at around 75,000. And that's on the high side of breakeven estimates. Anton Cheremukhin, economist at the Dallas Fed, puts it around 30,000, down from around 250,000 only two years ago. The problem is a low breakeven level of job growth may help cap the unemployment rate from rising too fast too soon, but it masks a deeper fragility in the labor market. It won't take much of a deterioration for slender net job growth to turn into net job losses. MESSAGE IN A BARREL The Fed is clearly aware of this risk, with Chair Powell indicating last month that the fear of rapid labor market deterioration was largely behind the decision to resume cutting interest rates even with inflation above the 2% target. And both the Fed and investors may have other reasons to look past the still-elevated inflation rate. For one, there's the signaling from the oil market. Granted, the connection between crude price and inflation is weaker than it used to be, but it shouldn't be ignored. Oil is languishing at five-month lows, with Brent crude near $60 a barrel. That's down around 15% from the same period last year. Most energy analysts, including those at the International Energy Agency, are forecasting a persistent imbalance between supply and demand in the coming year, both because of increased production and weakening demand. If Eurasia Group analysts are right, this glut could push prices as low as $55 a barrel by the end of this year, which would be a five-year low. Moderate oil prices have exerted downward pressure on inflation almost all year. Cheaper crude won't bring inflation back to the Fed's 2% target, of course, but it is one more factor that can help explain why the Fed and investors have shifted their focus from inflation to the creaky labor market. (The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters) By Jamie McGeever; Editing by Alex Richardson Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles., opens new tab Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias.