Copyright The Philadelphia Inquirer

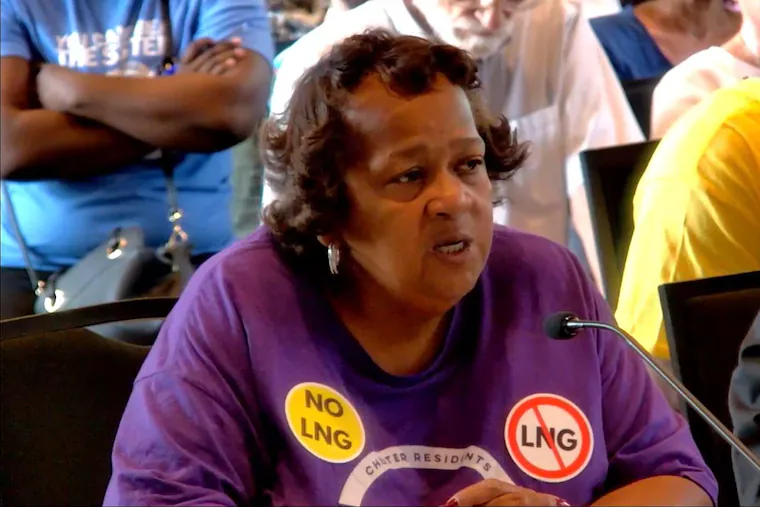

Chester Mayor Stefan Roots came up with an idea as he waited to testify Wednesday during a Pennsylvania legislative committee hearing on a proposed gas export terminal. “I’m introducing a new initiative,” he said, “WMO — we’ve moved on .… This dangerous facility does not belong in a densely populated urban area like Chester. I’m calling on this committee to do the right thing: Protect some of the most vulnerable people in this commonwealth and say no to an LNG terminal in this region.” Roots spoke in response to a yearslong plan by Penn LNG to build a liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminal in Chester or nearby in southeastern Pennsylvania along the Delaware River. The terminal would tap in to an existing pipeline to carry gas from the Marcellus and Utica formations to a site on the river. There, it would be compressed into liquid gas for export and capitalize on soaring global demand for LNG after Russian’s invasion of Ukraine. The hearing, held by the Pennsylvania House Environmental & Natural Resource Protection Committee, was stacked with opponents of the plan, saying it would create pollution and be highly dangerous to surrounding communities. Democratic State Rep. Greg Vitale, the committee chair from Delaware County, said proponents, including Franc James, CEO of Penn LNG, and union leaders were invited but declined. Penn LNG has not specified a location but has said it plans to develop a new plant to export 1 billion cubic feet per day of gas from the Marcellus Shale to Europe. At previous hearings held by Republican State Rep. Martina White, chair of the Philadelphia LNG Export Task Force, proponents spoke of the economic change the facility would bring, including jobs. Vitale said he convened Wednesday’s hearing because he feared the project would “proceed under the radar without sufficient public scrutiny.” Indeed, the mood Wednesday was strikingly different from past hearings as opponents told legislators an LNG facility would pose serious health, safety, and environmental justice issues. » READ MORE: ‘We suffer for everybody else’s comfort’: LNG facility proposed in Chester draws pushback What are the plans for the LNG facility? In 2024, former President Joe Biden put a pause on LNG export approvals in 2024 to further study the issue. This year President Donald Trump has made reviving fossil fuel energy projects a priority. Reuters reported in June that James, the Penn LNG CEO, had met with officials at the White House over the project. Penn LNG wants to export 7.2 million tons a year of LNG from a site near Philadelphia to markets in Europe and Asia and is considering several locations other than Chester, such as in Trainer, Marcus Hook, and Eddystone, the news service reported. What are the issues regarding an LNG facility? Opponents believe such a facility would pose a major threat if there is an explosion or fire in an area already densely populated with people and polluting industrial sites. They noted that Delaware County’s Crozer-Chester Medical Center and Springfield Hospital were closed this year amid a bankruptcy auction. If there is a catastrophic explosion, they said, the nearest hospital would be 30 minutes away. Tracy Carluccio, an advocate with the nonprofit Delaware Riverkeeper Network, said the area is too densely populated for the facility, emphasizing that a major concern is the lack of a sufficient safety buffer, which the federal government advises for LNG terminals. She noted that similar facilities in the South are situated in areas with thousands of acres of buffer. She said a new site in the area would likely be around 100 acres. “There is no location within the Delaware River watershed, including the bay all the way down to the ocean, for any LNG facility to be located,” Carluccio said. Lauren Minsky, a visiting professor of health studies at Haverford College, said an LNG facility would exacerbate existing public health issues in the region. She said southeastern Delaware County has already been given a grade of “F” for particle pollution and a grade of “D” for ozone levels by the American Lung Association. She cited 2025 research by Johns Hopkins University showing that high levels of volatile organic compounds have been measured in communities near the fence lines of LNG facilities. She also said there are elevated cancer rates in adults living in the area’s riverfront communities, citing the People’s Cancer Incidence Screening Tool, which calculates average annual cancer incidence rates in Pennsylvania. “If we value the health of our families, our friends and neighbors, and throughout the commonwealth, we need to build a different future, one in which we can all thrive,” she said. Already industrialized Zulene Mayfield, an activist with Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living, said older residents she knows have suffered heart conditions and cancers that she links to living in an already heavily industrialized area. Mayfield is a longtime opponent of the Delaware Valley Resource Recovery Facility owned by Reworld, formerly Covanta. The facility burns trash and converts it to energy. She said Chester, rimmed by heavy industry, lacks many things other communities take for granted, such as primary-care physicians or entertainment for children. “We are being told that we have to accept other industries” that no other communities want, Mayfield said. “I’m sitting here right now trying to contain my rage,” she said. “The jobs are temporary, but death is forever.”