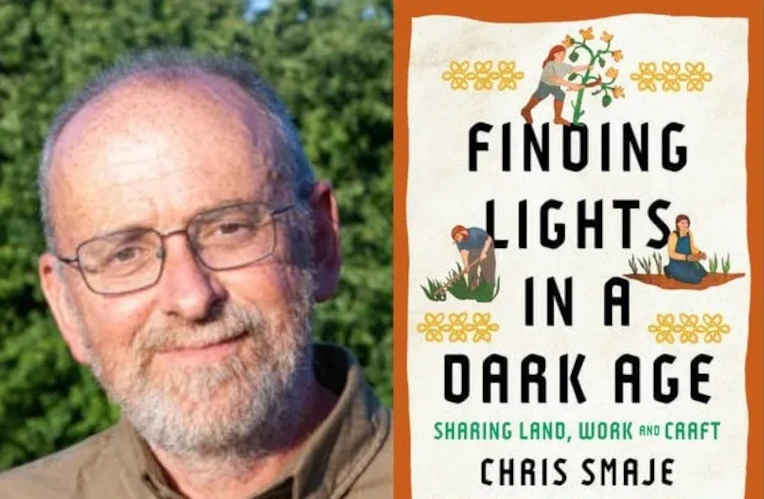

Copyright Resilience

To coincide with the US publication today of my new book Finding Lights in a Dark Age, I think it’s time to start writing some blog posts about it. I have a bit of unfinished business in relation to other projected posts, but hopefully I can sweep them up somewhere along the way. It’s going to be a slow tick over, though, because I don’t currently have much capacity to turn out blog posts at speed. I’ll begin by linking something I mention at the very start of the book with something I mention at the very end. At the start, I describe a process of climate change in early medieval times caused by volcanic activity which ultimately helped prompt the emergence of the Vikings as an expansionary and predatory force across an impressive stretch of the globe. I liken Viking society, both for good and (mostly) bad, to a gangster or pirate culture, with a code of honour that applies to its protagonists but not to its victims. This pirate culture, I argue, is a foundation of modern political culture more generally, even if its violence has often been more sublimated in recent times. People tend to forget this, assuming that violence outside an explicit social contract is just the inherent way of things. It is, for sure, one way that people have commonly done politics, and not only in medieval and modern Europe. But it’s not the only way, and this is worth remembering in our present troubled times. We’ve touched on this issue in recent discussions on this blog. At the end of the book, I give an acknowledgement to Marshall Sahlins and David Graeber, anthropologists of the Chicago ‘anarchist school’, who were more influential upon me in the writing of it than I’d anticipated. But when I wrote Finding Lights… I hadn’t yet read Graeber’s book Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia – perhaps slightly unfortunately in view of my opening piratical theme. Pirate Enlightenment was, according to Graeber, originally written as a chapter for a book he co-wrote with Sahlins called On Kings, which I did read before writing Finding Lights… I drew on its analysis of stranger kings to try to make some sense of our baffling contemporary politics – again, something touched on in recent blog posts and discussions. I won’t try to summarise Pirate Enlightenment here, but the mise-en-scène involves European pirates of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, who had originally been operating in the Atlantic and Caribbean, ultimately decamping to the northeast coast of Madagascar and settling. There, they were drawn into the complex political affairs of local Malagasy protagonists. In keeping with his wider project to take Euro-American self-importance down a peg or two, Graeber argues that the relatively egalitarian politics that emerged in this pirate-Malagasy encounter influenced the thinkers of the emerging Enlightenment back in Europe as they cast off the received wisdom of old hierarchies and developed modern conceptions of liberty. I’m in no position to judge the truth of this claim. I suspect Graeber may have over-egged his argument a little here. But the more general point about how new culture and politics often emerges conjointly out of the encounter between indigenes and incoming strangers, especially relatively high-status ones with colonial designs, is interesting. It’s a point I made historically in my book A Small Farm Future using examples particularly from the colonial Caribbean of the slavery era – an especially brutal form of domination out of which nevertheless new local cultural synthesis emerged. In Finding Lights… I make the point prospectively, arguing that new forms of local agrarian politics and practice are likely to emerge in the future as people seek what I call ‘open country’ – places where the landscape, the waterscape and the peoplescape are suited as best they can be to a peaceful and prosperous life. Contemporary discussion of such collapse scenarios seems to me often a bit too hidebound by existing political theories, or by ‘Viking’, ‘men with guns’, or Hobbesian thinking. In these collapse scenarios in open country, I write in Finding Lights… “neat pre-existing theories about the evils of landlordism, the benefits of land value tax, the nature of class struggle or the war of all against all are less to the point than how you configure new relationships on the ground. Right now, you’re unique participants in a complex drama of real human beings that you’re helping to write, not rote performers of old lines” (p.110). I’m not suggesting the world will be turned upside down and the meek will inherit the earth. I pay plenty of attention in the book to the way that naked power might assert itself. But I do think Graeber-esque attention to the complexities of political power and the way it can shift as people navigate its contours in new circumstances is appropriate. In that sense, arguably I paint too negative a picture of the Vikings in the book’s preface, because that complexity no doubt applied to them too. But what I’m trying to do in that preface is guard against over-breezy historical mythmaking of the Mussolini-made-the-trains-run-on-time variety: “Say what you like about the Vikings, they certainly boosted trade along the Dnieper”. Yeah, and in doing that, alongside all the slavery and death, they also tipped the scales that bit further against the possibility of ecologically wise localisms. And so I still hold to the wider point I was making via the Viking example when I wrote “The trading-raiding-slaving nexus of Viking-era globalization is our world, directly paralleling the globalization of modern centuries” (p.xiii). In other words there’s a need, in contemporary parlance, to ‘de-colonise’ our assumptions about the present world of globalism and its forms of violence, hidden or otherwise. Although that process has its complexities and difficulties too, which perhaps I’ll touch on in another post. Graeber points out that most European pirate crews in their seventeenth-century heyday were created out of mutiny against the brutal regimes aboard naval and merchant vessels. This meant certain death for them if captured, regardless of any piratical misadventures. The pirate flag often depicted an hourglass to symbolise this borrowed time and nothing-to-lose mentality. Pirates could often capture a lot of lucre, but – cut off as they were from the wider social connections that turned money into a flow of benefit – it was usually an empty form of plenty. Setting themselves up as stranger kings in Madagascar was one creative response. Perhaps we who are now so connected in a global world of lucre are living in the mirror of such brutal and empty pirate worlds, the sand running unnoticed through the hourglass. Which I guess is why I feel compelled to keep writing books like Finding Lights… and to keep talking about this, because it’s a perspective that gets drowned out by too much celebration of a modernism and Enlightenment sanitised of its piratical ways. Anyway, a couple more points before I close. Talking of sand and hourglasses, I went to a memorial on Saturday for Des Harris, a steadfast townsman of Frome for many years who helped us greatly nearly twenty years ago when we were establishing our site and market garden. He also taught people gardening skills on the allotments we established on our site, as shown in this picture – Des resplendent in his Eco-Worrier T-shirt. I coined the phrase ‘Dig With Des’ for these sessions, which somehow stuck. Later he took a course with Charles Dowding just down the road and became a convert to Charles’s methods, so it became Don’t Dig with Des. The memorial was a lovely, and crowded, event. Des touched a lot of lives with his commitment to serving the wider good. I fear that when I was in the throes of trying to establish a commercially viable market garden I sometimes exhibited a certain spikiness in his presence around things that seem unimportant now. Something of a character flaw, perhaps – although the tensions involved in being a community-minded local businessperson raise wider questions that I touch on in my book and that perhaps I’ll return to here in the future. In the meantime, I’ll venture the opinion that the kind of community connections that Des sought to build through his life are more fruitful than anything the Vikings built along the Dnieper. In the words of Linda Ellis’s sweet little poem The Dash, which was read out at the memorial, “If we could just slow down enough to consider what’s true and real…” And not only in our individual lives. Ain’t that true of our modern, pirate world writ large. Anyway, so long Des, and all good wishes for your onward journey. You were a great teacher, not just of gardening. And your dash was exemplary. Finally, the first full-length of review of Finding Lights… that I’ve seen is in, from the pen of the ever thought-provoking Hadden Turner. Happily for me, it’s a positive one, which is always nice to see. The only point Hadden makes that I’m inclined to unfold a little is this: “Chris is optimistic, and I wish I shared his optimism”. I don’t mind that description, given that I’m more often characterized as an unrelenting doomer – although I prefer to go with ‘hope’ than ‘optimism’. In truth, I’m not massively optimistic that the new dark age will turn out too well for many people, but I think once one has appraised the reality of the surrounding darkness it’s always worth looking for the light as best one can and seeking least worst responses to our predicaments. Whether we find it or not is another matter. Perhaps the book should have been called Looking for Lights in a Dark Age. Well, I’m glad it wasn’t. My preferred title was the more ambiguous Lights for a Dark Age, which also scans better. But we don’t always get what we want in life, a truth that I believe will soon be biting harder on a lot more people in the presently wealthy world. All eyes on the hourglass.