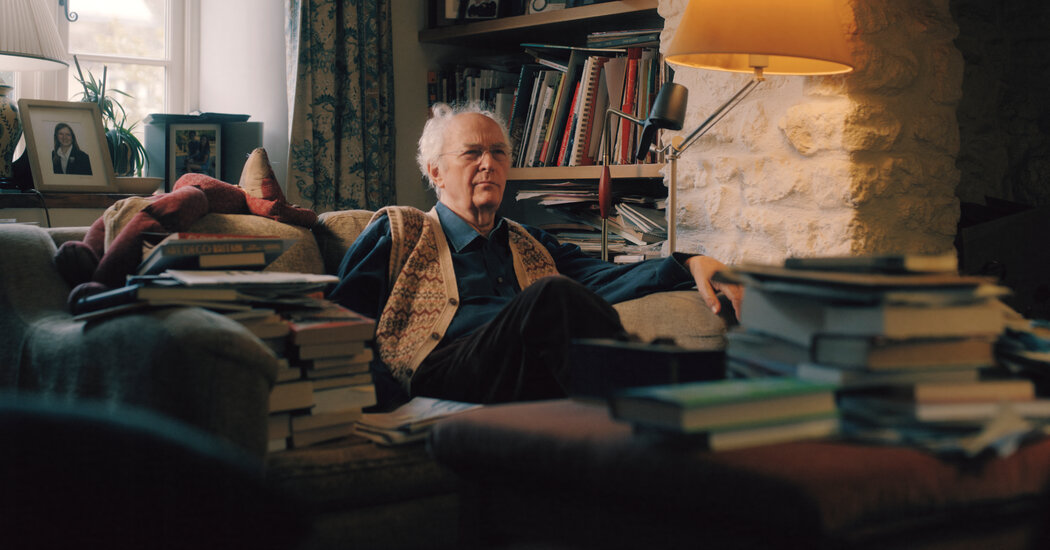

Copyright The New York Times

It’s been 30 years since the British author Philip Pullman published the first book in the beloved “His Dark Materials” trilogy, an epic adventure that also happens to be a daring retelling of Milton’s “Paradise Lost” in which the world is saved, rather than doomed, by original sin. Full of remarkable adventures alongside big ideas, the books introduced one of the most delightful devices in all of children’s literature: the animal daemons that reflect the characters’ souls and are with them always. The trilogy concluded in 2000, but Pullman returned in 2017 with “La Belle Sauvage,” the first book in a new trilogy that continued the tale of his indomitable heroine, Lyra Silvertongue (and her daemon, a pine marten named Pantalaimon). An “equal rather than a sequel,” as Pullman calls it, the second trilogy jumps backward and then forward in time, as an older Lyra contends with a growing darkness in the world and within herself. I first interviewed Pullman in 2000, after I fell under the spell of his intoxicating, multi-world story and its dazzling characters: passionate witches; fearsome polar bears who wear finely wrought armor they forge themselves; a race of tiny, hotheaded spies who have deadly poison embedded in their spurs. Talking to him felt like reading his books. He operates on many levels at once, not unlike his alethiometer, a complex watch-like device full of symbols that allows its skilled users to find answers to difficult questions. I’m hardly the only one who has lost sleep over these books. A friend recently told me that, unable to stop reading the second book in the series, “The Subtle Knife,” while she was waiting to pick up her son at school more than 20 years go, she burst into sobs in public at the death of a beloved character. The best-selling British children’s author Katherine Rundell said in a recent interview that Lyra, “with her stubborn love and unruly vividness” is her “favorite heroine in English children’s literature.” “Pullman changed the field,” Rundell said. “He showed how much can be asked of a child reader, how eagerly they will rise to meet vast ideas. The books understand that children crave stories on the epic scale, that infinity is not too large for them.” Pullman is suffering from various physical ailments, including long Covid, that have robbed him of some energy. But his conversation is as nimble and wide-ranging as ever. We’re interrupted from time to time by Mixie, the more boisterous of the household’s two cockapoos, who jumps on the sofa and offers me a stuffed alligator by way of greeting. Pullman decided to return to Lyra’s story, he said, because of where he’d left her back in 2000. Yes, she’d helped save the universe, but she was still so young, emerging from childhood into young adulthood. “What’s she going to do for the rest of her life?” he asked. “Learn Latin and French and play netball? I don’t think so.” “She needed another adventure,” he said. “Besides, she was getting to a stage in her life where interesting things go on.” In “La Belle Sauvage” (2017), which takes place before “His Dark Materials,” Lyra is an infant saved from her enemies and from a catastrophic flood by an industrious boy named Malcolm. Its sequel, “The Secret Commonwealth” (2019), jumps ahead to her life as a college student, at odds with both herself and the world around her, and “The Rose Field” begins the moment that story leaves off. The new book is full of wondrous things: Look especially for the touchy, egotistic gryphons, beasts with lions’ bodies and eagles’ heads, who worship gold and demand to be treated with elaborate respect. It’s also a plea for humanism and intellectual honesty in a world where the biggest villains are corporations, corrupt governments, a disdain for nature and a power-hungry, cruel church whose terrifying governing body is known as the Magisterium. Pullman has always resisted overt discussion of how his books might comment on current events, but it’s not hard to see what themes are preoccupying him. His writing works on two levels. On the surface is the story, which he sees as paramount. Underneath is an engagement with serious intellectual and metaphysical issues and a riot of allusions to other works — fairy tales, poems, novels, scientific treatises, philosophical texts, quantum physics — the fruits of a lifetime’s reading and study. If “Paradise Lost” was a driving force behind “His Dark Materials,” then Edmund Spenser’s 16th-century epic poem, “The Faerie Queen,” with its challenging episodic narrative, is an inspiration for the second trilogy. “I think a lot of the readers are surprised to find how steeped in history the books are and how much Pullman is borrowing from different historical elements and different literary texts,” said Kristen Poole, a professor of English at the University of Delaware and the author of “Philip Pullman and the Historical Imagination: Seventeenth-Century Literature, Science, and Religion in ‘His Dark Materials’ and ‘The Book of Dust.’” A small sampling: Pullman borrowed the notion of the “secret commonwealth,” a shadowy world that includes spirits, fairies, ghosts and other uncanny beings, from a book of that title by the 17th-century British writer Robert Kirk. Other influences are Heinrich von Kleist’s slim essay “On The Marionette Theater” (1810) — “a wonderful, extraordinary engagement with the difference between innocence and experience,” Pullman said — and Marshall Berman’s 1982 book about modernism, “All that is Solid Melts into Air,” whose title comes from a line in Marx and Engels’s “Communist Manifesto.” Raised in Wales, Pullman worked as a teacher before becoming a full-time writer and has written more than three dozen books, for adults as well as children. In 2017, he published “Daemon Voices: On Stories and Storytelling,” a collection of lectures and essays about his influences and his craft. He has won numerous awards and been the subject of countless academic studies; his books have been turned into films, plays and a TV series. In 2019, he received a knighthood for “services to literature.” “I’m most grateful of all to those who continue to read my books, and I hope they don’t have to work as hard as those who edit them,” he said at the time. Now at work on a memoir, Pullman says he feels satisfied now that the story of Lyra has come to an end. “Lyra’s found the answer to the mystery she was set off with in this book: ‘What is my imagination? Where has it gone? Why has it vanished?’” he said. “And she’s discovered that the imagination is a faculty of seeing, not of imagining,” that takes in “all the memories, resemblances, metaphors — all the things that are connected with the things we see.” Of all his creations, Pullman is most proud of his daemons, who reflect the characters’ understanding of themselves and whose narrative possibilities have expanded more creatively with each book. Because he has always said that no one can choose his own daemon (it’s up to our friends to identify the animal that best reflects us), it seems almost impertinent to broach the question: What sort of animal is his daemon?