Copyright tribuneonlineng

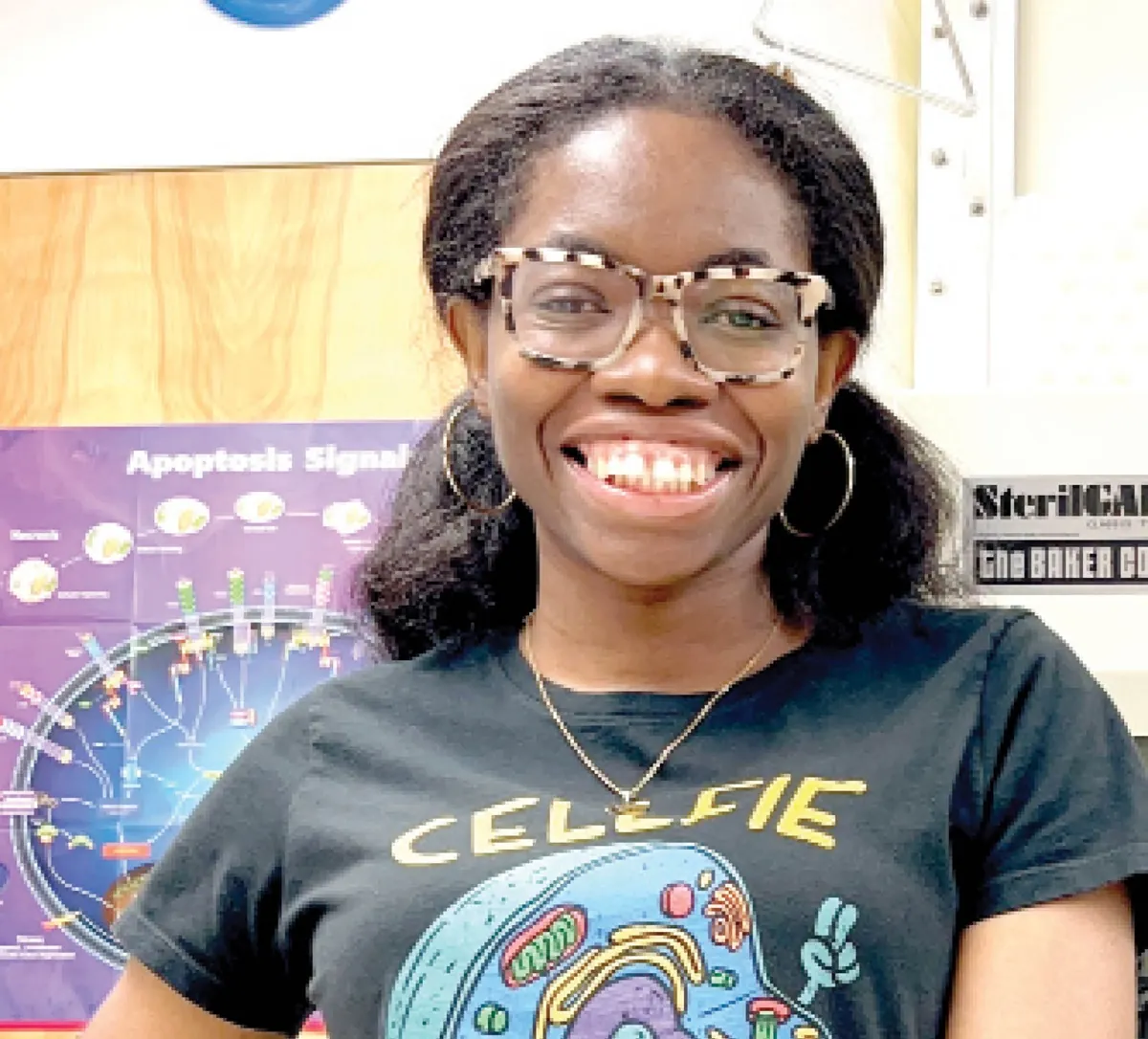

Deborah Agbakwuru studied and practised pharmacy in Nigeria before relocating to the United States to study immunology for her PhD at the University of Montana. Her research focuses on T cell biology and immune cell communication. In this interview by KINGSLEY ALUMONA, she speaks about her work, life in the US, among other issues. Who or what inspired your decision to study pharmacy? What was the best experience you had studying the course, and what were your career expectations upon graduation? Growing up, I was deeply curious about how drugs worked, how something so small could bring relief or even save a life. That curiosity grew into a desire to understand diseases and their treatments. Studying pharmacy was intense but deeply rewarding. It gave me a strong foundation in both science and empathy. My favourite experiences were during clinical rotations, standing face to face with patients and realising that every prescription represented trust, responsibility, and hope. When I graduated, I imagined a career in clinical pharmacy, perhaps managing hospital pharmacies or working in community pharmacies. And, for a few years, I did that in Nigeria. But as time went on, I felt a strong pull toward research, toward understanding why treatments work for some people but not for others. That unanswered “why” became the turning point in my journey. A few years after working as a pharmacist in Nigeria, you relocated to the United States for your PhD at the University of Montana. First, I could not find a record of your master’s degree. Why? Second, do you think doing a PhD in Nigeria is not good for you? I actually went straight into a PhD programme without doing a master’s. In the US, it is quite common for outstanding candidates to be admitted directly into PhD programmes if their academic record and research potential are strong. Doing a PhD in Nigeria is not bad. We have brilliant minds and strong institutions. But I was looking for very specific training, and at the time, such opportunities were limited back home. Tell us how you secured the Montana PhD and how you are funding it. I secured my PhD position through a competitive application process and funding from a departmental graduate assistantship. My funding covers tuition and living expenses. Your first degree was in pharmacy. Why did you decide to major in immunology and cell and molecular biology for your PhD programme? How does pharmacy relate to these areas of your work and research? I have always loved pharmacy, and I still love it. However, while practising as a pharmacist, I became intrigued by how the immune system determines whether a drug or therapy succeeds or fails. I wanted to move beyond dispensing medicines to understanding how the body itself responds to them. Pharmacy gave me the clinical foundation to ask the right questions, while immunology gives me the tools to find the answers. The two are deeply connected — every effective drug relies on the body’s biological systems to work properly. So now, my research explores how immune cells communicate, how they learn from interactions, and how that knowledge can be used to design better immunotherapies. This year, you were awarded the prestigious Besancon Scholarship. What does the scholarship mean to you and your work, and what do you intend to achieve with it? Receiving the Besancon Scholarship was a humbling and affirming moment. It is given annually to a University of Montana graduate student who demonstrates academic and research excellence. For me, it was more than an award; it was a reminder that my journey, though far from home, is making an impact. The scholarship allows me to focus more deeply on my research, attend conferences, and collaborate with other scientists. What is your PhD thesis about, and what are the potential findings from it? How do you think it can impact society? My research focuses on a fascinating process called trogocytosis, where immune cells “bite off” and acquire pieces of other cells during contact. I am investigating how the strength of T cell receptor (TCR) affinity, that is, how tightly a T cell binds to its target, affects this process and the signalling that follows. In simple terms, I am studying how T cells exchange information through touch. Understanding this could reveal why some immune responses are stronger or longer-lasting than others. If we can decode that, we could design better immunotherapies, improve vaccine responses, and perhaps even predict treatment outcomes for certain cancers. It is highly technical work, but the societal goal is clear — to make treatments more effective. In your bio, you noted passionately about a book chapter publication you wrote, titled ‘The biological significance of trogocytosis’. What is trogocytosis, and why are you interested in it? And, why should we be interested in it too? Trogocytosis literally means ‘cell eating by nibbling’. It is an incredible form of cellular communication, where immune cells take small bits of other cells’ membranes and use that information to fine-tune their responses. I became fascinated with it because it challenges the traditional view that cells only communicate through secreted signals. Here, they actually exchange pieces of themselves. We should all care about trogocytosis because it is central to how our immune system learns, adapts, and sometimes misfires. It is linked to cancer, autoimmunity, and infection. The more we understand it, the better we can design therapies that harness or correct it. Why is it that two people suffering the same type and stage of cancer — let us say lung cancer — and receiving the same type of treatment, but one dies from it, and the other survives it? How could you explain that? That is one of the biggest mysteries in medicine, and it boils down to biology’s diversity. No two people are biologically identical. Our genetics, immune systems, lifestyles, and even the microbes in our guts shape how we respond to disease and therapy. In cancer, the immune system plays a huge role. One person’s immune cells might recognise and destroy tumour cells effectively, while another’s might not. There is also tumour heterogeneity, where cancer cells evolve differently even within the same type of cancer. So, one patient might have a tumour that is sensitive to therapy, while another’s is resistant. That is why personalised medicine is the future, tailoring treatment based on each person’s unique biology, not just the disease. It is strange that most researchers are tirelessly working on finding the cure to cancer — even as reported cancer cases keep surging globally — with little research and campaigns on how to prevent it in the first place. Why is that? What natural ways of preventing cancer could you recommend? You are absolutely right. Prevention does not get as much attention as cure, but it is equally important. Part of the reason is that prevention is harder to measure and fund. A cure is more tangible. Prevention is a silent success because people who do not get sick rarely make the news. The truth is, lifestyle plays a huge role. Avoiding tobacco, limiting alcohol, eating fruits and vegetables, maintaining a healthy weight, and exercising regularly all reduce risk. Early screening and vaccinations, like HPV vaccines, also prevent certain cancers. From your expertise so far, how would you advise the Nigerian government and health sector stakeholders on how to approach cancer research and treatment, especially the way you have seen and experienced it done in the US? Nigeria has brilliant minds and a growing research community. What we need are stronger systems and investment in translational research, connecting laboratory findings to patient care. Government and private sectors should fund research consistently, not sporadically. We also need better research infrastructure, such as well-equipped labs, grant opportunities, mentorship programmes, and collaborations with international institutions. Most importantly, data sharing and ethics frameworks must be strengthened to build trust and global partnerships. If we can create environments where scientists are supported and appreciated, we will not just import solutions, we will develop our own. What advice do you have for people living with cancer? Have you ever imagined a world where cancer is the easiest disease to treat? How soon do you think that world would be realised? To everyone living with cancer, I would say: Hold on to hope. Science is advancing faster than ever. New immunotherapies are changing outcomes every day. But equally, your mental and emotional health matter. Surround yourself with support and believe that progress is real. I have imagined a world where cancer is no longer a death sentence. I think we are getting closer, step by step. It may not happen overnight, but the momentum is there. What are the major challenges you face in your studies and work, and how are you managing them? Behind work, what other extracurricular or social endeavours keep you busy at Montana? Research can be demanding — long hours, failed experiments, etc. The biggest challenge is often balancing this with self-care. But I remind myself that science is a marathon, not a sprint. I also find strength in God, my family, and my friends. Outside the lab, I volunteer with Letters to a Pre-Scientist, a pen-pal programme connecting STEM professionals to middle school students. Here, I share knowledge and inspire their curiosity in STEM. Montana’s natural beauty helps too. There are mountains everywhere, which is lovely to see and very calming. What is next for you after completing your PhD programme? Where would you like to work? And where do you see yourself and your career in five years? After my PhD, I hope to continue in translational immunology, bridging laboratory research with clinical application. I want to work in cancer immunotherapy, developing treatments that are both effective and accessible. In five years, I see myself leading a research team or working within an organisation that combines science, education, and advocacy. Ultimately, I want to be part of the global effort to make advanced therapies available to communities that need them most, including in Nigeria. My journey began in Nigeria, and no matter where science takes me, that is the heartbeat behind everything I do.