Copyright Deadline

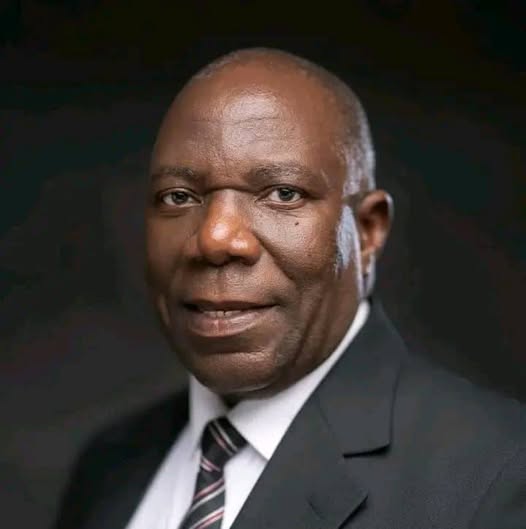

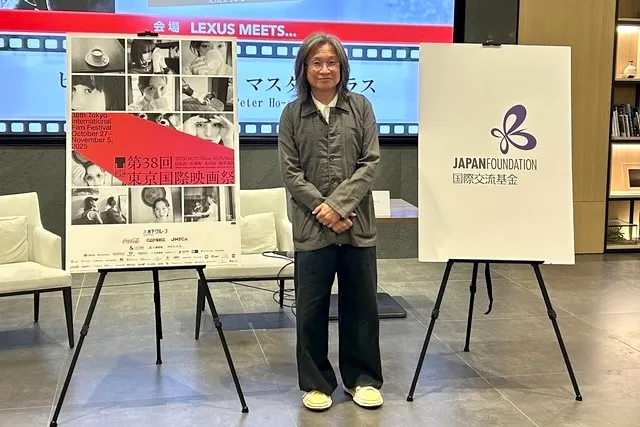

Hong Kong filmmaker Peter Ho-sun Chan talked through the many changes he’s seen in the Asian film business during his 35-year career in a TIFF Lounge Masterclass at Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF). He also teased when we might get to see the second part of his period crime drama She Has No Name, the first part of which is playing in the Galas section at this year’s TIFF. In conversation with TIFF Programming Director Shozo Ichiyama, Chan mapped out the different stages of his career, starting with personal Hong Kong dramas like He’s A Woman, She’s A Man and Comrades: Almost A Love Story in the 1990s; a stint in Hollywood and a phase of pioneering pan-Asian co-productions; before moving on to big-budget mainland Chinese epics such as The Warlords and Dragon (Wu Xia) in the mid-2000s, and more recently China-set dramas including Dearest, sports biopic Leap and Zhang Ziyi starrer She Has No Name. He reminisced about how much he enjoyed visiting TIFF back in the 1990s, not long after co-founding Hong Kong-based United Filmmakers Organization (UFO), when the festival was still located in Shibuya. “Back in those days, Hong Kong cinema was still very messy,” Chan remembered. “Not like now in China with bigger budgets; everything was low budget, we were making movies in five or six weeks and releasing them five days after wrap. “So every time we came to Japan, it was like, wow, they take film so seriously here! We felt like we were being treated like very important people. It was a really great time, and also the best time of Hong Kong cinema.” Chan founded UFO in the early 1990s with a group of like-minded filmmakers because “we didn’t know how to make comedy, gangster, martial arts films, so we didn’t fit into the Hong Kong film industry”. But he says that when the company got started, the Hong Kong film business was already in decline. One of the problems, he explained, was that the Hong Kong market was too small, the China market hadn’t emerged yet, so everyone was relying on Taiwan, a market that was starting to turn it back on Hong Kong movies: “Taiwan distributors were starting to dictate what kind of movies Hong Kong people should be making and they kept asking for the same thing. So it’s like you’re driving and always looking in the rear-view mirror. “There’s this phenomenon, a crisis really, from back then that has lasted until today. Even in Hollywood with the streamers, everybody’s looking at the big data, the algorithm, so you’re not making movies for the future, you’re making them for the past.” The crisis point came around 1994 when Taiwanese distributors decided to stop outbidding each other for Hong Kong movies and turned their attention to Hollywood fare instead. By the early 2000s, the market share of Chinese and other foreign films in the Taiwan market had collapsed to less than 2%. Following a stint in Hollywood, a rite of passage during which he made English-language drama The Love Letter for DreamWorks, Chan returned to Asia and started producing movies with filmmakers from across the continent – Jan Dara and The Eye with Thai talent, One Fine Spring Day with Korea and pan-Asian co-production Three. “At that stage, I realized I’m not a horror film director, but the films that can actually cross borders and work business-wise are always horror. But I can’t keep directing horror films, so I finally decided to go to China.” Over the years, Chan has seen the mainland Chinese film industry grow from a standing start into the behemoth it is today and become much more corporate. But in the early 2000s, it was still all up for grabs. Chan’s first mainland movie, musical drama Perhaps Love (2005), starring Takeshi Kaneshiro and Jackie Cheung, was a cross-border project in its own way, inspired by Bollywood musicals and employing the talents of Indian choreographer Farah Khan. Following that movie, he went all in on big-budget Chinese epics starting with The Warlords (2007), which has cult status now but was criticized at the time for not having enough action. “Out of two hours and 15 minutes, it only had about 15-20 minutes of action. And it wasn’t the Jet Li kind of martial arts action, it was war-style action and was really a drama. “So finally, I had to make a movie that is not so deceiving for the audience. So I make Wu Xia, which has a a lot of fight scenes, and I really have to credit Donnie Yen and Kenji [Japanese action choreographer Kenji Tanigaki]. They were the people who helped me with the action. I was only doing the characters and the drama.” Although he’s still based in Hong Kong, Chan said it’s difficult to make movies in his hometown because it’s a market that will always be small, but the growth of the China market has pumped up prices for cast and crew. So he explained that he took another detour with more character-driven mainland films like American Dreams In China, which revolves around three young entrepreneurs in Beijing; Dearest, about child abduction in rural China; and biographical sports drama Leap. He also made a biopic about Chinese tennis champion Li Na in 2018, which is understood to be stalled in censorship in China. Chan has also remained active as a producer, working with directors including Derek Tsang, producing his 2016 drama Soulmate, before the Hong Kong filmmaker went on to direct Netflix series 3 Body Problem, and Japanese filmmaker Shunji Iwai, producing his 2018 romantic drama Love Letter. “It’s very easy producing Shunji, because you don’t have to do anything, all you need to do is introduce him to the right people, the actors and investors, because he’s like a one-man band,” Chan said. “Being on his set is amazing because he just runs around the set and does everything himself.” He also talked through the ten-year process of making She Has No Name, which tells the real-life story of a woman who was accused of murdering and dismembering her husband in 1940s Shanghai. While he usually works with his own teams of writers, he took on the project as a completed script. “It was the first time I’d been given a script and thought I have to make this – there was so much in the script that I loved – and when I gave it to Zhang Ziyi she committed in a flash. But I had to pull the plug two months before production, because it was too expensive. It wasn’t commercial enough at that price and it was also too long.” Chan shelved the project while he made Li Na and Leap, finally returning to it and shooting a film of two hours and 30 minutes duration that premiered at the 2024 edition of Cannes. But he felt that version was too choppy and started editing again. “I was supposed to edit it down to two hours, which I couldn’t do, so I ended up turning the film back to four hours, and I was happy with that version, but nobody’s going to watch a four-hour movie. So I cut it into four parts, hoping it could become a TV series, but a four-part series would not be able to recoup the budget that we spent.” Long story short, Chan cut the film into two parts, the first of which played as the opening film of this year’s Shanghai International Film Festival and screened today here at TIFF. Chan said the second part will be released next year: “I hope we can come back to [Tokyo] film festival next year”, and that he’s still exploring ways to release it as a series. “Part two has more human emotion, because we see a lot more of the characters’ emotions, including her relationship with her so-called lover that everybody suspected of helping her commit the crime,” Chan said. “There’s also a whole chunk about the relationship between her and the husband, how the marriage turned sour, and how he became a violent wife-beater.” Speaking to Deadline on the sidelines of the event, Chan said he’s recently returned to developing international co-productions, working with filmmakers in Thailand and India on projects targeting global audiences. He launched Changin’ Pictures in 2022 to work on pan-Asian streaming series, but is now also looking at international films. “It’s not a case of which country we’re working with, but which filmmakers; we’re identifying directors who could become international,” said Chan. “We like to work with people who are happy to get out of their comfort zone, who have a reputation in their own territory, but want to work on something that could be international. And in that case, most possibly, it needs to be something that is at least half in the English language.” The TIFF Lounge series of talks continues tomorrow with a conversation between Thai director Pen-ek Ratanaruang, whose Morte Cucina is playing in TIFF competition, and Japanese filmmaker Akio Fujimoto (Lost Land).