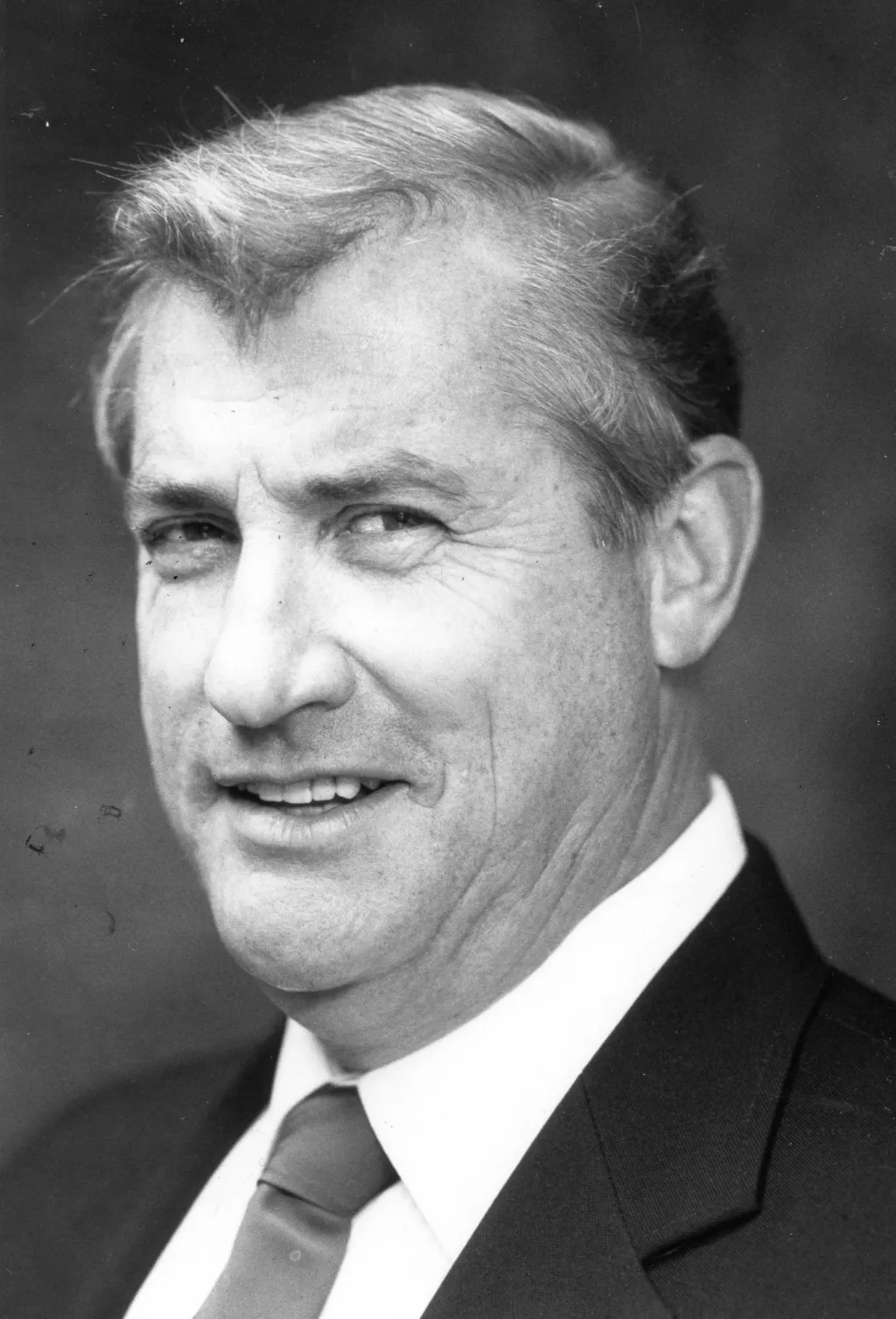

Pete Callinan, Rohnert Park’s first mayor and city manager, architect of a booming city, dies at 94

There is a story told about Pete Callinan that sounds apocryphal but is true.

It occurred decades ago, back when Callinan was the first city manager in Rohnert Park, the newly established city carved from a former seed farm. Callinan, deeply invested in every step the city made, was a wee bit miffed when the City Council balked at making a tough decision.

On what issue matters little at this point.

Ticked at what he perceived as weakness in the face of a difficult call, Callinan was reported to have tossed each elected official a copy of President John F. Kennedy’s book “Profiles in Courage,” and suggested they grow a firmer backbone.

“He wasn’t afraid to make a decision, right or wrong,” said his son, Joe Callinan. “That is how I was raised, make a decision and move on.”

Callinan, who was also Rohnert Park’s first mayor and was credited as being a key architect in the development of Sonoma County’s third largest city, died Sept. 10 in his Rohnert Park home. He was 94.

As one of a group of post-World War II civic and business people who reshaped the region from a rural Bay Area outpost into a booming suburban hub, Callinan arrived in 1959 from Oakland, where he was working as an accountant. He was newly married with a young child and the family were in search of an affordable home with a manageable commute to the East Bay.

He found nothing.

That is, until he found Rohnert Park. A small community that was not yet an official city, its neighborhoods were being plotted and built by Paul Golis and Maurice Fredericks on the old 2,600-acre Rohnert Seed Farm north of Cotati.

Callinan, his wife Greta and their young daughter Joyce, settled into a home on Arlen Drive. The price tag on that home was $12,000.

Almost immediately, Callinan, a finance guy with a degree in accounting, became a member of the Rohnert Park District Board of Directors.

Then, in 1962, just two years after initially rejecting the idea, voters changed course and approved the incorporation of Rohnert Park as Sonoma County’s seventh city.

In the first council election, Callinan received the most votes and became the town’s first mayor.

A year later, in 1963, city leaders asked Callinan if he would be willing to quit his job in Oakland and take the reins as the city’s first city manager.

“I kicked it around with my wife,” Callinan told The Press Democrat in 1990. “(I) said ‘What the hell, you don’t get a chance to start a city every day.’”

Largely unburdened by existing housing tracts or long-standing regulations, Callinan and city leaders were set loose to implement their vision for the city.

“Pete had blank land to develop all the things he wanted to do,” said Art Hollingsworth, a city council member who served for two decades before retiring in 1995. “Fifty-two years ago, we had one stop sign, one shop. He had a vision of what the city should look like and he carried it out.”

The vision touted single-family homes grouped into neighborhoods designated by letters of the alphabet, with pools, parks and ball fields for each, and a performing art center and community gymnasium for the city as a whole.

The Callinan family first settled in the north-central A section, and the kids had the run of the place, said daughter Joyce Miller.

“We lived on Arlen Drive and there was nothing across the street from us,” she said. “We had ‘A pool’ but it was like we had a family membership. We had a baseball field right there. My dad coached all the boys. We were always at a ball game somewhere.”

Callinan was a tireless cheerleader for the city. He recruited professionals to set up shop in town and bristled when anyone doubted the appeal of The Friendly City, Rohnert Park’s self-appointed nickname.

He chafed at coffee-shop chatter or news stories that discounted its charm.

Criticism of the decentralized city for having no core — or “no there-there” as writer Gertrude Stein once famously said of Oakland — was wildly off the mark, he believed.

“The reason we have parks and pools isn’t to have parks and pools but to have them because they’re used,” he once told a Press Democrat reporter. “Nothing we’ve done has sat idle.”

Callinan was invested in the success of Rohnert Park in a way that isn’t likely to be replicated, said Joe Netter, who succeeded him as city manager in 1991.

“He really cared about the city, it was his life,” he said. “He was very respectful and kind, but demanding as a city manager. I can’t say enough about his philosophies, his willingness to help people, his willingness to do the right thing.”

From projects large and small, Callinan grew a reputation as a get-it-done administrator. In one news story printed upon his retirement, he was described by colleagues as a “benevolent dictator” who ran the city with “a tight fist.”

He was not a behind the scenes bureaucrat. He let his feelings be known.

“They pay me a pretty good salary and I’d feel guilty if I didn’t get them the benefit of my thoughts,” he told a Press Democrat reporter.

He was known to roll out the welcome mat to developers, but to also demand substantial commitment in return — like the building of parks and cultural amenities.

“You treat them like human being, you have a dialogue and then you ask them to leave a little bit behind,” he told a Press Democrat reporter in 1990.

Son Joe Callinan, who later also served on the Rohnert Park council and was a two-time mayor, remembers driving the streets in the family car as a kid when his dad would suddenly take note of something amiss.

“He’d say, ‘Write this down: There is a stop sign that is leaning,’” the younger Callinan said. “The next day it would be fixed.”

Small wins were important, but so were big ones.

Callinan is credited with luring State Farm from Santa Rosa to Rohnert Park in the 1970s, a massive boon to his city, where the insurance giant served as a major employer until its pullout in 2011. Today, its demolished former campus is now the site of a planned downtown district for the city that Callinan and others believed did not need one, hueing to a strictly suburban vision for the community popular at the time.

Callinan owed much of his success and long tenure to his considerable charm, said longtime friend and golf partner Don Davis, who was encouraged by Callinan to establish his dental practice in town.

“He didn’t say ‘Why don’t you?’ He said, ‘We have a dental business that is almost finished and it’s got a waiting room with our first and only physician,’” he said.

“Pete was the right guy in the right place,” Davis said. “He made you feel like this might be a good place to raise a family. He was aggressive but not too aggressive. He did it the right way. He made you feel at home when you didn’t have one.”

Callinan was instrumental in establishing the city’s pioneering public safety department — a combination of police and fire services, and one of only two such hybrid agencies operating in the state.

He was also a key player in the 1976 establishment of the Redwood Empire Municipal Insurance Fund, a joint powers authority meant to handle claims, benefit programs and risk management for members cities.

But as much as Callinan symbolized for his era the skillful leader of a rapidly growing city, Netter remembers him for his nurturing mentorship, bestowed on many members of his immediate staff and across the city. He honored his municipal employees and put the city first, Netter said.

“I grew up in a family without a father,” he said. “If I could choose a father, if I had that choice, it would be somebody like Pete Callinan. That’s how highly I put him in my life.”

Pete Callinan was born Nov. 26, 1930 in Newark, New Jersey to Rosina and Joseph Callinan.

He served in the U.S. Air Force and earned his accounting degree from Seton Hall University.

His retirement from the city in 1990 ushered in a long part of his post-work life that included traveling in his recreational vehicle with Greta and frequent trips to the ocean.

Plus, with a brood as large as the Callinan clan, there was always a family event in the works, his daughter Joyce said.

“There was always something going on, somebody’s birthday, a baby shower, somebody getting married,” she said.

He was preceded in death by his wife, Greta, and a son, Peter.

In addition to his daughter, Joyce, and son, Joe, both of Rohnert Park, he is survived by sons Christopher of Grass Valley, Gary, Joseph and Jeffrey, all of Rohnert Park, and 16 grandchildren.

A celebration of life is scheduled from 1-5 p.m. Oct. 19 at the Rohnert Park Community Center, 5401 Snyder Lane.