Copyright Salt Lake City Deseret News

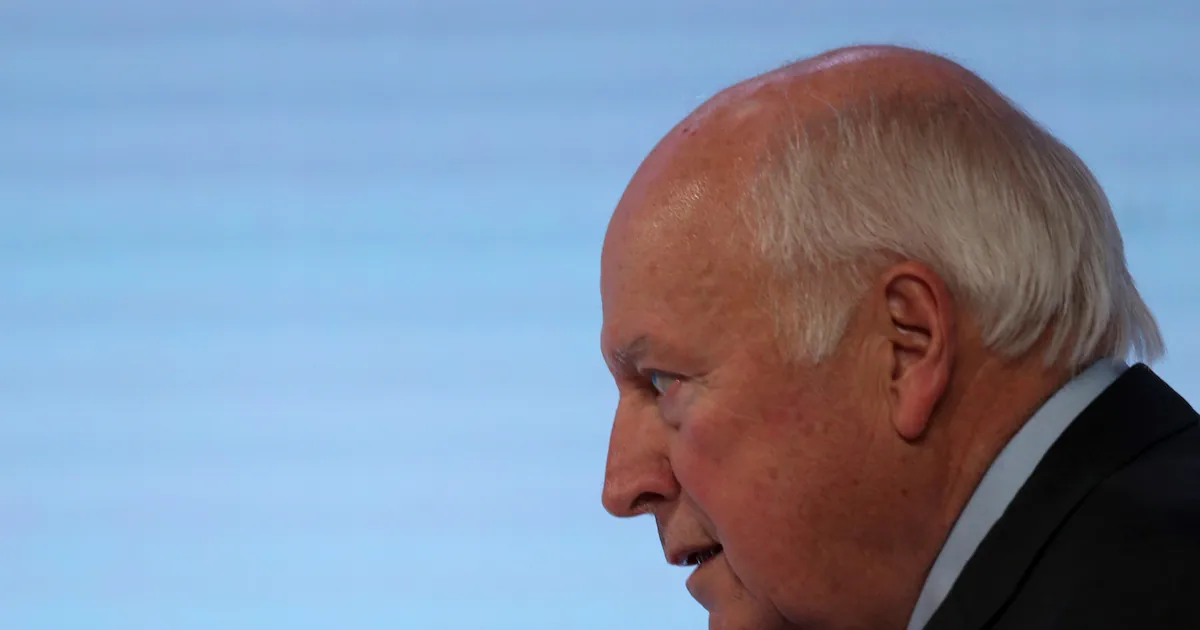

Former Vice President Dick Cheney died last Tuesday at the age of 84. He was disliked by a majority of the public both during and after his vice presidency, including most Democrats and a large section of Republicans. That ire came for multiple reasons, one of which is because he stood up to the mob, when others would rather pander. Some were frustrated at the perception he was a “warmonger” who promoted unwise policies after 9/11. Others disliked him because they claimed he was a fierce partisan who didn’t always follow polite pieties. Still others disliked him because, despite being a longtime conservative Republican stalwart, he supported Kamala Harris for president, calling Donald Trump a “coward” for refusing to be honest about his defeat in 2020. There is no doubt that each of these stances earned him enemies. But none fully explain the ire directed at Cheney. For instance, even people who defend the Iraq War admit major failings with post-9/11 actions Cheny was involved in, and the collapse of Afghanistan in 2021 has caused many to question the last 25 years of American foreign policy. But President George W. Bush held more-or-less the same positions, and while he’s taken his lumps, he’s now viewed more positively than negatively. And if we take off partisan blinders, it’s worth noting that most of the positions held by Cheney after 9/11, including on the Iraq War, were also held by Hillary Clinton, John Kerry and Joe Biden. As the Wall Street Journal recently pointed out, Cheney’s unique contribution was helping save Iraq vis a vis the “surge” when others who had supported the war wanted to shirk responsibility. One common response is to paint Cheney as some sort of Rasputin-like character, cynically manipulating the powers that be. According to this narrative, Cheney was “really” to blame, even if others did the deed. This, too, has the semblance of a real argument. Cheney was, undoubtedly, one of the most experienced people in government ever to hold high office. Starting in 1966, he’d been a congressional aid, a Nixon Administration official, President Gerald Ford’s chief of staff, minority whip in the U.S. House of Representatives, and secretary of defense before becoming vice president in 2001. When Cheney became vice president, Bush was still green as a national leader. While partisan Democrats liked to paint George W. Bush as stupid and easily manipulated, no learned person sincerely believes that now. As Stanford lecturer Keith Hennessy, an accomplished economist who worked in the Bush White House for six years, told his students: “President Bush is smarter than almost every one of you.” And how could one sincerely believe that Cheney could manipulate both Bush and his most fierce critics, like Kerry, Clinton and Biden, at the same time, with very little formal power? Cheney was often seen as fiercely partisan. This is partly true. You don’t get to be the Republican whip in Congress without knowing how to throw partisan punches. But there is other evidence that challenges this stereotype. For instance, Cheney, and the wider Bush team, took active steps in 2006 to ensure his former vice presidential rival, Joe Lieberman, remained in the Senate as an “independent Democrat,” because he viewed Lieberman’s support on key national security matters as more important than partisanship. Likewise, his support for Kamala Harris in 2024 showed he was willing to put what he saw as best for his country over party. Cheney also took a stance on gay marriage all the way back to 2004, well before any national Democrat held that position openly, that was unpopular at the time. Since President Bush was on the opposite side, and most gay marriage supporters were Democrats, it became easy to forget Cheney’s stance. Cheney believed in the post-World War II order where America was preeminent over its foes, and that freedom and democracy at home was worthwhile for its own sake. He subsequently helped safeguard the international order he supported. The Republican Party, which he believed best articulated those views at the time, was treated by Cheney as a vehicle. When he saw threats to freedom, at home or abroad, he acted accordingly, even when others didn’t see the threat or articulate it as he did. Cheney stuck by these beliefs, to his personal political detriment, but not to the detriment of the causes he championed. Indeed, a better reading of the situation is that Cheney’s critics dislike him because he was unapologetic about his stances, controversial as they may be, and he fought effectively for them. Cheney never gave his critics the satisfaction of watching him retreat from stances he believed to be right, and they loathed him for it. Cheney believed he was promoting the best interests of his country, and was much less concerned about the shorter-term, personal ramifications. This stands in contrast to most politicians, and most national leaders today. Most senior officials in the Trump Administration, most notably the president himself, zigzag wildly on issues with no clear north star beyond their own immediate political interests, with a lot of senior Congressional leaders following suit. Meanwhile, the Democrats pander to increasingly fringe segments of society on divisive identity politics. Harris lost, in significant part, because she struggled to pivot away from fringe positions she’d held just a few years earlier, like supporting taxpayer funded sex reassignment surgery for illegal immigrants. Cheney’s position on Trump further clarifies what drove him. By supporting Harris, the former vice president won few friends. Already loathed by the left, supporting Harris changed few Democratic minds. Indeed, it became a common (and silly) complaint on the hard left that Harris lost because she spent too much time campaigning with Cheney’s daughter Liz, who shared her father’s opinion on Trump’s threat to democracy. But Cheney’s stance did further alienate the party he’d spent his life serving. To many younger Republicans, the Cheney name now amounts to a cuss word. But most politicians, on all sides, are far less willing to take personal or political risks for their beliefs when they prove unpopular. And yet approval ratings for Congress, for President Trump and senior Democrats all remain poor. What Cheney showed is that politics ebbs and flows. Sometimes unpopularity is inevitable. Better to stand by your convictions, and make a difference, than pander in a likely vain attempt to stay marginally more popular. We should want more people like Cheney boldly defending their views in public life and not pandering to the latest whim. Doing so takes guts. And guts is something Cheney had. Big time.