The University of Pennsylvania admitted about 20% fewer doctoral students this year across its schools, citing proposals by President Donald Trump’s administration that threaten hundreds of millions of its federal research dollars.

And educators are concerned it’s only going to get worse. They fear that reducing doctoral students, if this continues over several years, ultimately could mean fewer teachers for undergraduate students, less research and less innovation.

The Ivy League university stands to lose about $250 million in research funding if courts allow a federal proposal to limit indirect cost reimbursements from the National Institutes of Health to proceed. The uncertainty resulted in theuniversity bringing in 527 new doctoral students this fall, down from 656 last year. That includes doctoral admissions to its School of Arts & Sciences, as well as its medical, nursing, communication, engineering, business, design and social policy andpractice schools and its Graduate School of Education.

It’s already beginning to have an impact on teaching, research and educational opportunities, professors say.

» READ MORE: Penn stands to lose $250 million from threatened cuts to scientific research funds under Trump

“We’ve had trouble finding graduate students to run our courses that we would normally have graduate students teach,” said Jessa Lingel, an associate professor who directs the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program in Penn’s School of Arts & Sciences, the largest of 12 schools at Penn. “The pinch is just starting to be felt, but it’s getting worse.”

Her pop culture class typically enrolls between 50 to 75 students.

“If I can’t find teaching assistants, the class can’t run,” she said, adding that she has enough for this year.

Admitting fewer graduate students could slow down research and endanger America’s competitive edge, said Carl June, a pioneering cancer scientist and professor in immunotherapy at Penn.

China, in comparison, is not cutting back on research, he said.

“We’re at the cusp of many new curative therapies, but if we don’t have the people to do the work, it won’t happen,” he said.

Penn, like the nation’s other elite colleges, has been under scrutiny since Trump took office in January. The administration’s attempt to cap NIH reimbursements at 15% is currently halted due to a court injunction. The administration also threatened $175 million in funding to Penn over the participation of a trans athlete on the women’s swim team, but Penn struck an agreement with the U.S. Department of Education in July.

Additionally, the federal excise tax on the university’s endowment earnings will rise from 1.4% to 4% under the budget bill that was signed by Trump in July. Penn paid $10.4 million in fiscal year 2024.

» READ MORE: Penn strikes agreement with Trump administration over trans athletes

Harvard and the University of Chicago are among other top research schools that have reduced, or plan to reduce, some doctoral student admissions over concerns about federal funding.

Locally, the University of Delaware made 725 offers of admission this year, down 19.5% from last year’s 901.

“Research agendas across the country stand to be impacted by this,” said Damani White-Lewis, a professor in Penn’s Graduate School of Education. “When you take fewer students who can then serve on your projects, that’s just fewer hours you can devote to a project, which may then make it more difficult for faculty to fill all the holes they need to fill and may mean longer hours for faculty.”

That, he said, could have “cascading impacts on the entire higher education eco-system.”

And it’s just one piece of a chilling effect on the research pipeline that also hits postdoctoral research opportunities, fellowships, and faculty jobs.

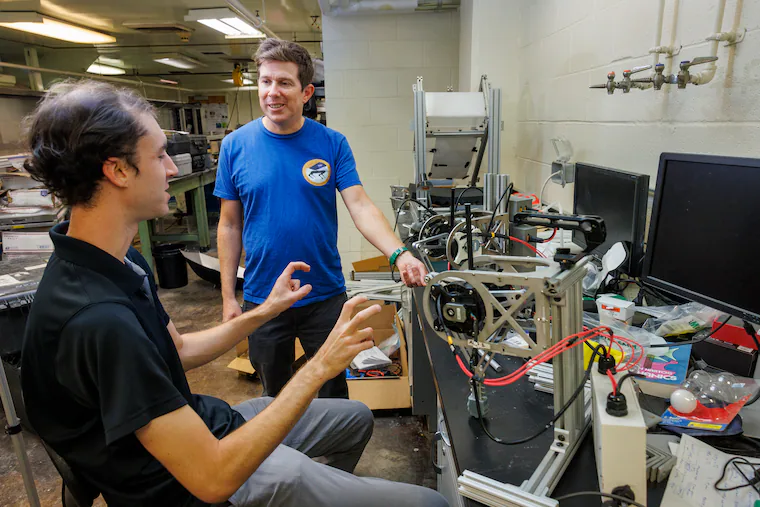

“If this were to happen for several years such that our graduate student population is reduced by 50%, that would be a major problem,” said Douglas Jerolmack, a Penn geophysics professor whose department in Penn’s School of Arts & Sciences admitted two new doctoral students instead of three or four like in past years.

The school overall admitted 172 doctoral students, down more than 20% from 217 students last year.

» READ MORE: Penn faculty criticize university plan to reduce graduate admissions by a third in response to NIH funding cuts

More cutbacks could mean having to admit fewer undergraduates or diminish the educational experience at some point because graduate students play a major role in teaching and assisting professors, he said.

Twenty-two graduate chairs in Arts & Sciences objected to the planned reduction last winter, asserting there already were too few graduate students to cover courses and that it would be detrimental to learning. Some professors were placed in the uncomfortable position of having to rescind offers to doctoral candidates.

‘Dreams deferred’

Jeffrey Kallberg, who had been serving as interim dean when the NIH funding cuts became public, said in a letter to faculty that the admission reductions were “a necessary cost-saving measure to help mitigate the impact of these new funding realities.”

The impact of the Trump administration’s threats has rippled through Jerolmack’s lab. He’s kept on four out of five of his lab workers for another year because their postdoctoral and doctoral opportunities and, in one case, a faculty job, vanished amid funding fears.

“One of them was all but certain to receive a NASA fellowship that was then eliminated,” he said, noting the fellowship would have been at the Goddard Space Flight Center.

Another doctoral student was turned down by multiple schools that were not awarding new postdoctoral fellowships, while a postdoctoral researcher who works in his lab was a finalist for three faculty jobs but lost out after all three searches were canceled, he said.

An undergraduate who was a strong doctoral candidate was rejected by schools that said they didn’t have resources to offer admission, he said. The student would have been a likely candidate for a National Science Foundation fellowship, but only received an honorable mention. That was after NSF earlier this year shrunk its number of fellowships from 2,000 to 1,000.

“These people spent five years, most of them in their 20s, working with the expectation of finding some career on the other side,” said Jerolmack, who has worked at Penn for 18 years and also has an appointment in the engineering school. “So it’s extending this period of uncertainty.”

As a result of keeping those four young people working in his lab, Jerolmack wasn’t able to bring new doctoral students in, leaving potential new scientists scrambling for opportunities.

“It’s dreams deferred,” he said.

Jerolmack was able to keep his lab workers because he hasn’t lost grants or funding. But he has not heard back from the NSF on several proposals and expected he would have by now.

Jerolmack said he understands administrators were in a tough position.

But Lingel, who also is the president of Penn’s American Association of University Professors chapter, faults university leadership for not including faculty in the decision-making about doctoral admission cuts.

“You should not make top down decisions that directly affect our research and teaching without any meaningful faculty input,” she said.

Overall, Penn admitted 114 students into the Biomedical Graduate Studies program at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine. That’s down nearly 26% from the average of 154 in each of the last four years.

The biomedical sciences program provides fully funded training positions covering tuition, fees, health insurance, and a living stipend. The positions are primarily funded by federal research and training grants, the school said.

The decision was driven by uncertainty about future federal grant support, said Michael Ostap, the medical school’s chief scientific officer.

“This was an unfortunate but necessary step to ensure that students who enroll continue to receive the high level of support and training that is essential to their success,” he said.

Andy Vaughan, an associate professor of biomedical science, credited the leadership in biomedical graduate studies and the cell molecular biology program with informing professors early about the reduction in admissions. His graduate work is through the medical school.

Forty percent fewer admissions offers were made in his graduate group this year, he said, but most accepted, mitigating the impact.

In the developmental biology group, nine of 11 students offered admission accepted, he said.

Vaughan worries that future funding instability could impact Penn’s ability to train more students. After the first one to two years of funding, the cost for the doctoral students is absorbed by individual labs and departments, he said.

“Anecdotally, there’s a lot of hesitation on the part of professors to take new graduate students into our labs because we are all very worried about whether the funding stream is going to continue,” he said.

With fewer lab spots, doctoral students pivot

That hesitancy to accept new students has resulted in some not being able to join their desired labs, said Thomas Zhang, a fourth-year PhD candidate at the medical school and president of the Biomedical Graduate Student Association.

Spots that normally would have been available to them were suddenly cut when grants were frozen or terminated. Those students have had to pivot by doing an extra rotation, which is like a several-week audition to join a lab.

Even graduate students who have found labs are finding it challenging to secure grants.

One of Zhang’s friends was awarded a competitive NIH grant to support the next few years of her research. It was abruptly cut this year, Zhang said, leaving her unable to pursue that project.

This was research that the government had originally determined to be “pressing and innovative,” and that could have informed the development of new cancer therapies, Zhang said.

“We don’t know if one thing is going to be the next cure for cancer, but now we have one fewer chance,” he said.

Will Penn further reduce doctoral admissions?

Penn hasn’t started the doctoral student admissions process for this year; Vaughan said he hasn’t heard whether reduced doctoral admissions will continue.

But at a board of trustees’ committee meeting Thursday, Mark Dingfield, Penn’s executive vice president, said the administration remains wary of funding losses, even while its endowment grew from $22.3 billion to $24.8 billion and its net assets grew by $2.9 billion to $33.9 billion.

He noted that “endowment income, research, and tuition are all subject to changes in federal policy” that could reduce the school’s revenue in coming years.

“Despite the really strong operating performance that we realized last year, there remains considerable uncertainty regarding our core operating revenues,” he said.

The administration will evaluate whether additional cost savings measures are needed, he said.