Copyright Athlon Sports

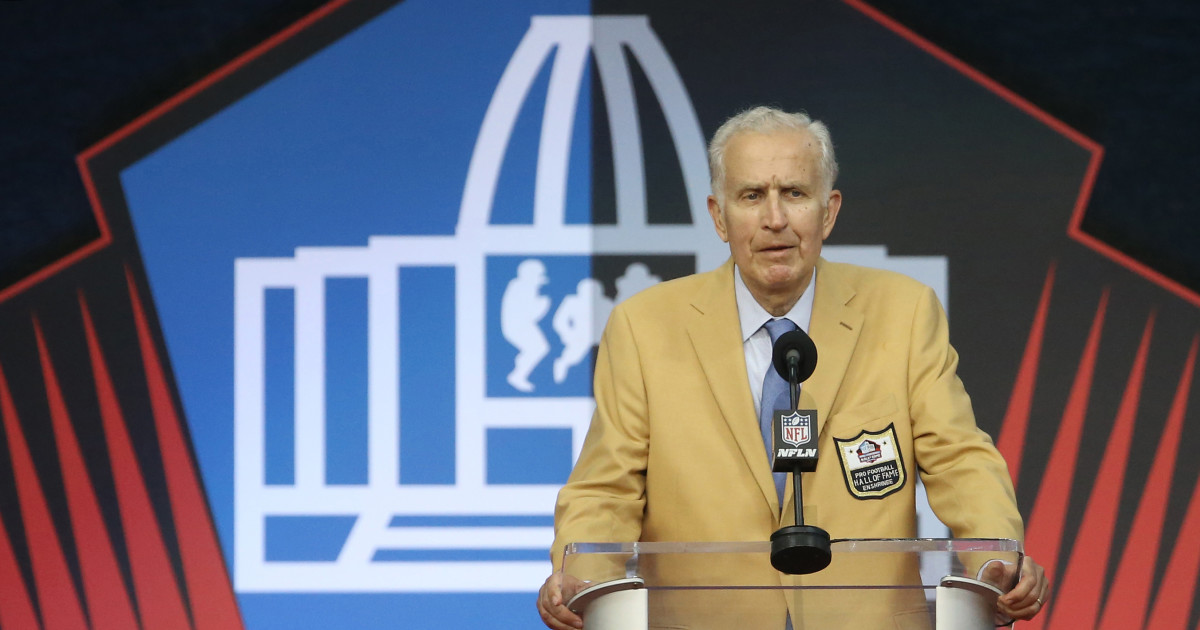

Paul Tagliabue, the NFL’s Commissioner from 1989 through 2006, who stewarded the league through everything from the beginnings of free agency to the aftereffects of Hurricane Katrina, died on Sunday morning at the age of 84. The reported cause of death was heart failure complicated by Parkinson’s disease. During his time as Commissioner, Tagliabue oversaw a league in which the values of franchise increased over and over, four new expansion teams (the Carolina Panthers, Jacksonville Jaguars, Cleveland Browns, and Houston Texans) were established “In examining what makes the NFL so compelling, I always return to the players who make the game what it is,” Tagliabue said during his Pro Football Hall of Fame induction speech in 2020. “The athletes who thrive in the competitive environment of the National Football League tend to be intensely motivated individuals with clear values and exceptional goals. We need to respect the players for having these qualities and for what they represent as leaders in sports and in society.” A lovely sentiment, but we can’t ignore what Tagliabue himself ignored throughout his time as Commissioner — the prevention and effects of head trauma on those players. Tagliabue seemed to see the increased focus on the effects of head trauma as a nuisance at best. Among the things I wrote for USA Today in 2020, after Tagliabue was enshrined in the Hall: During a 1994 summit at the New York City YMCA titled “Major League Commissioners Tackle the Future of Major League Sports.” NBA commissioner David Stern and NHL commissioner Gary Bettman were also on the panel, which was moderated by the late Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Halberstam, When Halberstam turned the talk to the effects of head trauma, especially as it pertained to the retirements of Troy Aikman, Steve Young, Merril Hoge and Al Toon, Tagliabue was not pleased at all. He dismissed the increased furor as “one of those pack-journalism issues.” He also said then that the number of concussions “is relatively small; the problem is the journalist issue.” That same year, Tagliabue established the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee, ostensibly to study the effects of head trauma. To lead this committee, Tagliabue appointed Elliot Pellman, a Guadalajara-educated rheumatologist with no expertise in head trauma. No results from this group were published until 2003, which became an understandable response over time. Pellman and his colleagues wrote in January 2005 that returning to play after a concussion “does not involve significant risk of a second injury either in the same game or during the season.” The group also stated repeatedly that there was “no evidence of worsening injury or chronic cumulative effects of multiple MTBIs in NFL players.” With a more qualified independent physician at the helm (Pellman also served as Tagliabue’s personal physician), NFL players would have known the full measure of their eventual fates years before they did. The NFL’s eventual settlement with more than 4,000 former players and their families was the result of a series of lawsuits seeking to stamp the NFL with its own liability in this regard. One of the conditions of the settlement was a gag order on years of malfeasance, a huge boon for a league. In a 2017 interview with the Talk of Fame Network, Tagliabue tried to stem the damage of his remarks with an after-the-fact apology. “Obviously, I do regret those remarks,” he said. “Looking back, it was not sensible language to use to express my thoughts at the time. My language was intemperate, and it led to serious misunderstanding. I overreacted on issues which we were already working on. But that doesn’t excuse the overreaction and intemperate language.” Tagliabue also addressed Pellman’s appointment, a move recommended by then-New York Jets owner Leon Hess. “Hess said that he was a hard worker, he was highly intelligent, he was a good organizer and he could work effectively with coaches and players,” Tagliabue explained, “and he was willing to stand up for the medical point of view and not be cowed. So I put Dr. Pellman in charge, knowing what his specialties were. “It was truly based on track record that these men had with their teams and what I thought they could help us accomplish with internal change.” “Throughout his decades-long leadership on behalf of the NFL, first as outside counsel and then during a powerful 17-year tenure as commissioner, Paul served with integrity, passion and an unwavering conviction to do what was best for the league,” current Commissioner Roger Goodell said in a statement after Tagliabue’s passing was announced. “Paul was the ultimate steward of the game—tall in stature, humble in presence and decisive in his loyalty to the NFL. He viewed every challenge and opportunity through the lens of what was best for the greater good, a principle he inherited from Pete Rozelle and passed on to me. “During his Hall of Fame NFL career, Paul fostered labor peace with our players, oversaw the expansion of the league to 32 teams, ushered in an era of state-of-the-art stadiums and laid the important groundwork of establishing the league as a global brand. “He helped modernize the structure of the league office and its business operations, providing the playbook for the NFL’s strategic embrace of his era’s emerging technologies including cable, satellite and the internet.” All of these things are true. On the whole, Tagliabue was a highly effective and considerate executive. But the one thing he let go of the rope on throughout his time in office left ramifications that the league continues to deal with to this day.