One solution for representing the internet-augmented discontinuity of contemporary life is the fragment novel. Seas of white space separate paragraphs, which together compose archipelago chapters; themes and subjects wash from one island to another; and voice is like climate, general across the complex. The fractured self, which is taken to be a microcosm of the fractured world, achieves coherence this way. Disparate phenomena become a whole system. But this form, popular in the pre-COVID days and lampooned in Lauren Oyler’s 2021 novel Fake Accounts and in a Joyce Carol Oates tweet from the same year that called its representatives “wan little husks,” can seem quaint in the wake of the virus’s massive disruptions and death toll — particularly if one’s setting is the pandemic era itself.

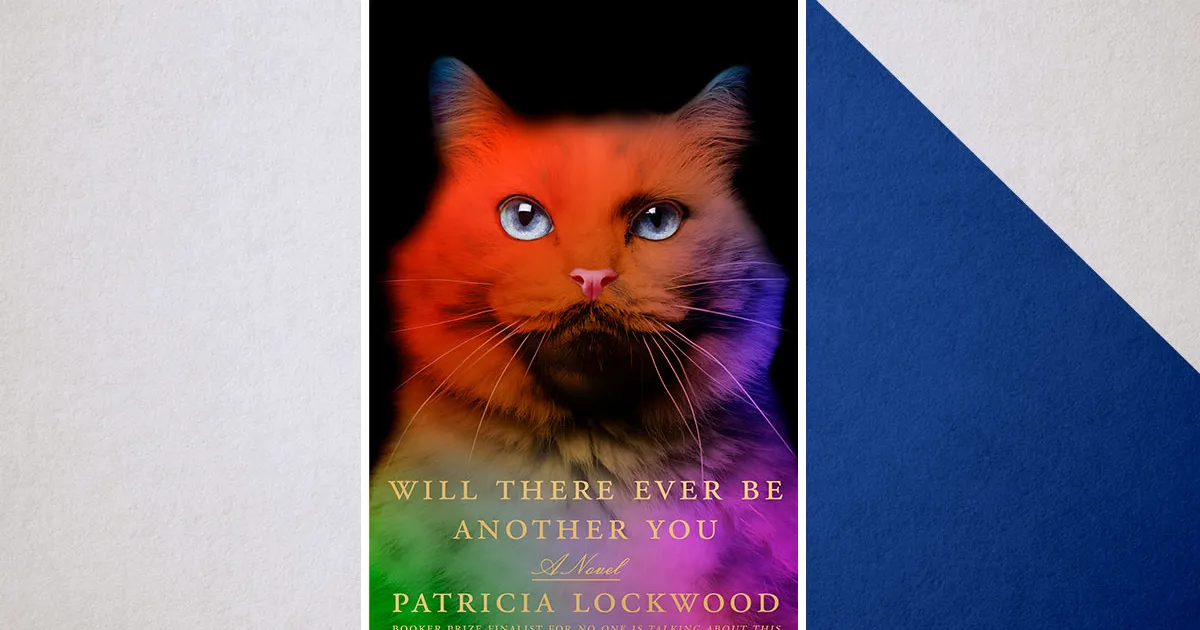

Perhaps this is why Patricia Lockwood — whose first book of fiction, No One Is Talking About This, ranks among the best recent fragment novels — has mostly abandoned this approach for her prismatic second effort, Will There Ever Be Another You. A febrile, poetic autofiction about one woman’s experience of COVID and its brain-breaking aftermath, the book self-consciously aspires to achieve a fresh form in order to depict a phenomenon overwhelming in its spatiotemporal scale. “A hyperobject, a Louis Wain cat, I said, when anyone asked what I was doing,” she writes at the tail end of her book. “The challenge was to find a new style for a new materiality.” Elsewhere, more facetiously: “I was going to write a masterpiece about being confused.” What she’s produced is a searching, pointedly disorienting text, studded with passages of extreme beauty and generous humor, that wears whimsy like a shivering veil over consuming discomfort, even terror. It is less consummately pleasurable, page by page, than No One; it is uneven; occasionally it drags. But because it is a work that seeks to capture the deranging effects of the recent past, confusion is a powerful lens.

Lockwood first came to notice in the early 2010s by posting ribald jokes and poetry on what was then called Twitter; she proceeded to release two poetry collections and, in 2017, a sui generis memoir, Priestdaddy, her breakthrough, about growing up in a series of rectories with her increasingly conservative, bigger-than-life Catholic preacher father. (The failed adaptation of that book into a television show figures into the narrative of Will There.) A position as contributing editor at the London Review of Books, where she reliably publishes 6,000-word barnburners on the Plaths and Foster Wallaces of the world, as well as essays on colonic malfeasance and meeting the pope, followed. Her star rose higher still in 2021, with the publication of the Booker-shortlisted No One, an autofiction that twists the broken cadences and piquant concerns of the internet into heartrending art about Being Online and the brief life of her niece, who died of a rare genetic disorder in infancy.

If her new novel has a plot, it concerns the struggle to be well and to write well after a shattering case of COVID in March 2020 and in the midst of its yearslong aftershocks. (Lockwood published a nonfiction piece about her experience of COVID in a July 2020 London Review of Books essay titled “Insane After Coronavirus?”; we glimpse her stand-in struggling to finish a piece like it, and others recognizable from her oeuvre, in the novel.) The book is a kind of illness travelogue in which the wily poet-author’s avatar shows up every day in a new mind and body, and often in a new place, with rejiggered symptoms, and attempts to win her reborn self’s favor, or at least its mercy. In some chapters, she narrates; in others, she’s “she.” The title is taken from a Time magazine cover from 1997 featuring Dolly, the cloned sheep. There it terminates in a question mark; here it doesn’t. There will be another you, and another, and another. Lockwood’s protagonist encounters doppelgängers; she recreates herself in a TV pilot and pandemic journals; and, of course, illness transforms her, again and again. “It stole people from themselves,” Lockwood writes of the virus. “You might look the same to others, but you had been replaced.” Lockwood has learned and repurposed this trick of estrangement. Her novel exerts a maddening power; it is — and I mean this as a compliment — a kind of poetic mind virus, infecting the reader with its strange rhythms, its alien logics, its addled relation to time, and its ideas about the ever-evolving, ever-dissolving self.

The book picks up, thematically, where No One ended, with a lost phone. In that book, when a thief took the narrator’s device out of her pocket, the loss amounted to a gift: Lockwood’s avatar had loosened her ties to the digital plane. Now, some months later, during a pre-COVID trip to Scotland, the niece’s mother has lost her phone, one that “had been in the hospital with them, in the right hand, always,” and anxiety has replaced grace. Will the past be lost along with all the photos stored on the device? The phone turns up, but the fear of disconnection that its brief absence awakens sounds a warning shot. When COVID comes for Lockwood’s protagonist, she becomes unglued and sheds her connections to our already-threadbare shared reality.

Most of the book’s subsequent 18 chapters defy easy summary. (There is also an epilogue.) In one, the protagonist’s husband nearly dies from a freak gut condition and its unsuccessful remedy. In another, she teaches a Walter Benjamin essay to a relative. Many chapters hurtle between time periods. The text foists us into aestheticized befuddlement: dozens of literary and pop-culture proper nouns (Sheila Heti, Liam Neeson, Tweety Bird), pandemic news items, articles of internet detritus, and family crises whip through the text and smash against each other, carried on the high winds of Lockwood’s cyclonic voice. She sees things that aren’t there — “Purple blotches over people’s faces, a violent prismatic hole in the center of my vision, a zigzag in the corner of my eye that I referred to as the angel” — and endures alien-hand syndrome, a rare neurological condition in which a person loses conscious control of a limb. A video of a live performance of Radiohead’s “Creep” features in Lockwood’s first novel, and here she dedicates a chapter called “Hidden Track” to Kid A: “The first five notes pressed down keys in her chest, and then the synthesized sound of the singer’s voice began wobbling up like bubbles.” One could crudely relate the books in these terms. A compact, pop-rock track that organizes alienation and crisis into a smash hit has been succeeded by a denser, weirder work.

Reading Lockwood, you might suspect that she enjoys access to a semi-controllable rendition of “dissolving margins,” the condition that afflicts Lila, the deuteragonist of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet, and which causes the borders between objects and phenomena to collapse and their convolution to overwhelm her. “A vast overidentification marked me, with people, with landscapes, with tender bends in plants, as if I were a kudzu overtaking the earth,” Lockwood writes in Will There. This porousness, evident in much of her writing, has intensified in this novel. At one point, her avatar wonders of the virus, “Had it optimized her?” Certainly Lockwood’s skill with metaphors has not waned. “The soul is a floor,” she writes in one chapter. “It is there to bear us up and keep us standing, not merely to be clean.” Nor have her sentences lost their capacity to circle and strafe their subjects, to fly above them, to feign disinterest for a clause or a paragraph before landing on them with comic force.

What has been lost (or sacrificed) is the continuous thrill-ride ecstasy of No One, where short, crystalline paragraphs propel the reader ever onward. Lockwood’s criticism tends to benefit from the focus the objects of her analysis provide. To carry a sprawling, feverish novel on voice is difficult work, and in Will There, she uses chapters centered on a psilocybin-tinged reading of Anna Karenina and her husband’s grievous illness to counterbalance the diffuse flow of others and connect distant sections. The interviewer at one of the narrator’s book readings quotes King Lear’s “Never, never, never, never, never” and a version of it returns later as “Not possible, not possible, not possible, not possible,” as Lockwood’s heroine cares for her husband, and then soon after, movingly, as “OK OK OK OK.” Still, at times in the novel I did want something solid to hold to, or the pace would slacken and I’d crave rapid forward movement.

But in its efforts to disorient and madden, Will There Ever Be Another You made me question these desires; I no longer always felt certain, after finishing it, that my qualms were qualms. “Did a thing to be glimpsed — health, illness, sanity — maintain its solidity from moment to moment?” Lockwood asks on the book’s penultimate page. She provides no answer. To swing the reader between states of sureness and perplexity, to disrupt and confuse his reception of the book, to create in him “another you” and another and another over the course of the text and in his rereadings: This is another solution for representing the discontinuity of contemporary life. Turning over the last page, I asked with pleasure, What was that?