Copyright newstatesman

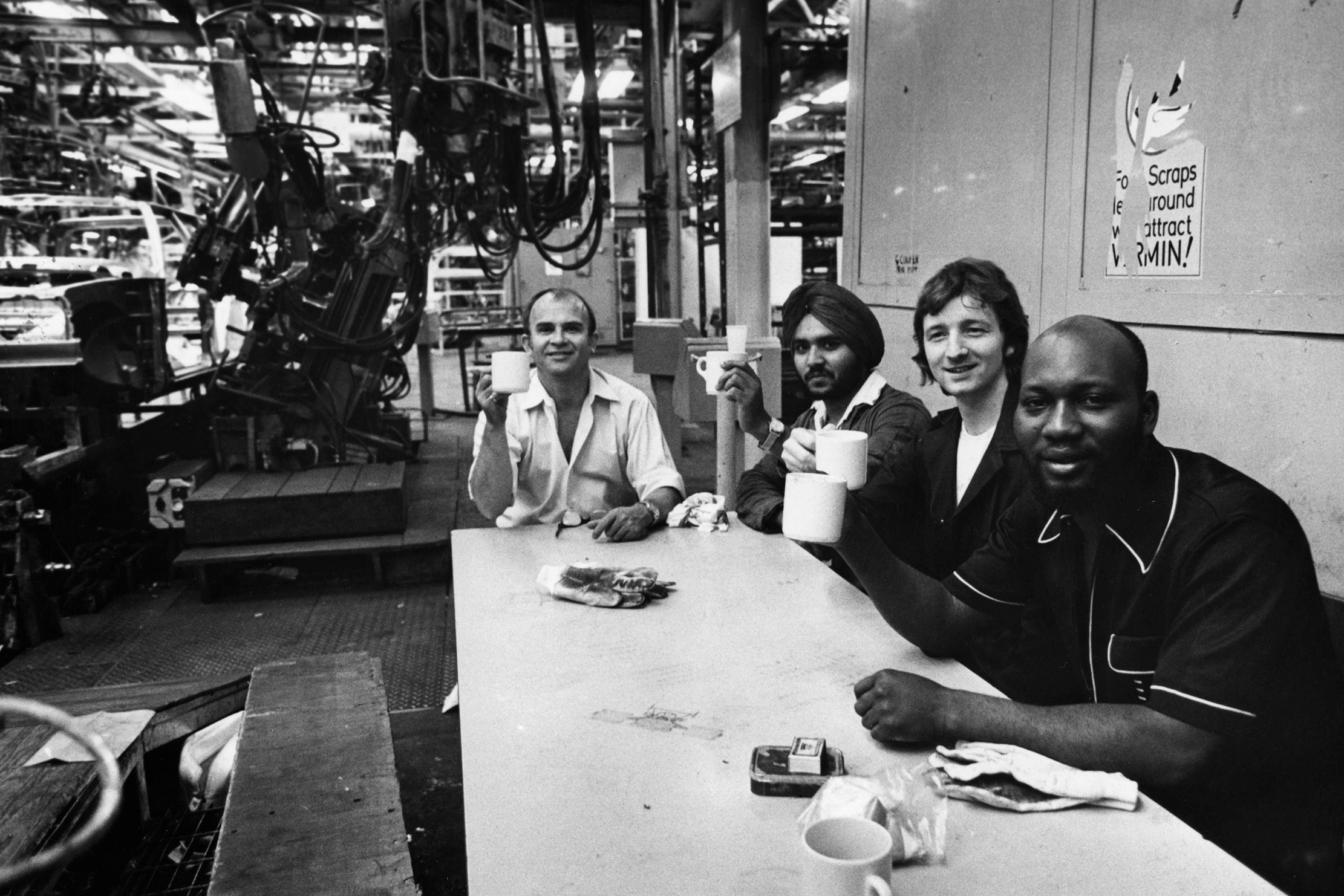

Three weeks before the 2024 US presidential election, I was sitting in a heavily air-conditioned room on the east coast of America, with leaders from various US organisations and institutions, describing how the latest research from the UCL Policy Lab had shown the need for politics and political institutions to “respect and respond to ordinary people’s lives, their concerns and daily challenges”. The first question caught me totally off guard. “Do you worry that phrases like ‘ordinary people’ are seen as a mainly white framing?” I’d never heard anything like this. Part of the thrust of our work was to break down the barriers between working-class communities and politics. This was about places across Britain where working-class communities were diverse; it included “red wall” seats where working-class sometimes meant being British Asian. In fact, the disconnection was often felt more acutely in these places, as recent politics has shown. It was one of many moments on that trip that reminded me that Britain is not America. At least not yet. No matter how many West Wing clips eager politicos watch or multi-volume histories they read, for all the showy American-style rhetorical flourishes of the moment, we are not close cousins. That great shining city on the hill has become a place of political division and mistrust, where language has a kind of electric double meaning, where the painful legacies of history weigh down on the present. The American people may still share a love and passion for their families and their country, but, as my conversation showed, they are talking past one another in politics. And yet it would be churlish to pretend that the possibility of American-style political division does not loom over Britain. A new right-wing nationalism is leading in the polls, the language of “remigration” is being spoken by rising stars in the Conservative party, and many feel happy to roll out attacks on the rules and norms that have governed our politics. But if we aren’t America yet, what’s holding us back from the kind of democratic slide we see across the pond? Speak to any scholar and they’ll point out that one crucial defence against a more anti-democratic or divisive political climate is the strength of shared institutions. New research from the UCL Policy Lab and More in Common has given some clear pointers. The report aims to understand how Britain views one of its great British institutions: our universities. In it, we find a country that shares pride, whether conservative or progressive, the global success of its local universities. This may be owing to universities’ refusal to become too wedded to an aggressive form of partisan politics, and to their commitment to remaining grounded not in politics but in place: teaching students, conducting research and tackling local needs, be it Manchester on regional growth or UCL on social cohesion. British people are proud of their universities as institutions that foster disagreement and discussion. And they view them as both local and national bodies. Be it Loughborough or Nottingham, the public views these institutions as a cause for civic pride. The polling found that 63 per cent said universities had a positive impact on the country, while only 6 per cent said they had a negative impact. This sits in stark contrast to the US, where support for universities falls much more neatly along party lines, with a growing number of Republicans viewing universities as antithetical to their form of politics. Why does this matter? Well, one answer is the importance of shared institutions that people believe in and that serve an identifiably common good. These are the bedrock of cohesion in difficult times. We know all too well that for many western countries, these are materially trying times – economic growth, geopolitics and failing political systems mean we fall back on the strength of our institutions. They become central to maintaining a conversation across disagreement. However much the cost-of-living matters (and it really does), it’s notable that, despite America’s surging economic growth, we are witnessing how a lack of shared institutions are enabling a slide towards a breakdown of democratic order. It’s why to avoid a similar fate, Britain’s institutions must remain rooted in place and among the people – reflective not just of those who attend or run them, but also of the communities in which they exist. Failure to do so would be a fatal mistake. Here again, polling shows that British institutions shouldn’t be complacent, with some warning signs for our universities. There is a clear sign that graduates are far more positive about universities than non-graduates (81 per cent versus 55 per cent). Non-graduates are more likely to see universities as benefiting only students and as rigged in favour of the wealthy. Staying alive to these concerns is crucial. It is vital that our universities and other institutions – museums, organisations like the National Trust or the BBC – remain open to everyone. Working-class families must see these institutions as serving not only those who reach the top but also those who want to build a life where they live. This is about providing good jobs, but also about responding to everyday challenges. For universities, this is also about research. Voters across education levels and political allegiances see it as one of the most important roles universities play, and they view universities more positively when informed about university research: discovering vaccines, inventing new technologies for industry or processes for bringing down waiting lists – all research being done at some of our leading universities. We must ensure our shared institutions are part of the nation’s natural fabric and part of the places where they are located. That while they call back to a deep history of Britain, they also reflect and speak to Britain as it is today – not static, but moving with us. Institutions should be reflective and respectful of the lives of those who will never walk their halls or be awarded the highest honours, who may never truly nail the latest theory or social norm. And universities have to respect those who chose other roots. The polling finds that the public supports expanding apprenticeships and other forms of training, as well as maintaining university education. As Michael Spence, leader of UCL, recently said, “Universities make a mistake when they say: ‘Look at us, aren’t we fabulous, we’re saving the world. And everybody needs a university degree, in one way or another.’” When I was growing up, my own grandmother was immensely proud of her children, not because they were scientists or graduates but because she’d brought them up to become nurses, teachers and boiler engineers. To my grandmother, they’d achieve the world and more; it was a pride not found in titles but in a respect that came from a kind of shared work for a common good. There is no doubt that our culture, technology and economy have become Americanised. If Britain wants to avoid America’s political fate, its institutions must remain rooted in people and place.