After encouraging podcast listeners of the recently deceased Charlie Kirk to become online vigilantes in search of anyone “celebrating” Mr. Kirk’s death, Vice President JD Vance said last week: “We don’t believe in political violence, but we do believe in civility. And there is no civility in the celebration of political assassination.”

Vance was doing what conservatives often do — conjuring people so his followers have someone specific to foment against. This brand of demagoguery is incredibly dangerous, because when informally deputized vigilantes realize that few real enemies exist, they accept any substitute. They direct their manufactured ire toward innocent people, marginalized groups and, eventually, each other.

Civility is the mode of engagement that is often demanded in political discourse; it is the price of admission to important political conversation, its adherents would have us believe; no civility, no service. But civility — this idea that there is a perfect, polite way to communicate about sociopolitical differences — is a fantasy.

The people who call for civility harbor the belief that we can contend with challenging ideas, and we can be open to changing our minds and we can be well mannered even in the face of significant differences. For such an atmosphere to exist, we would have to forget everything that makes us who we are. We would have to believe, despite so much evidence to the contrary, that the world is a fair and just place. And we would have to have nothing at stake.

In the fantasy of civility, if we are polite about our disagreements, we are practicing politics the right way. If we are polite when we express bigotry, we are performing respectability for people whom we do not actually respect and who, in return, do not respect us. The performance is the only thing that matters.

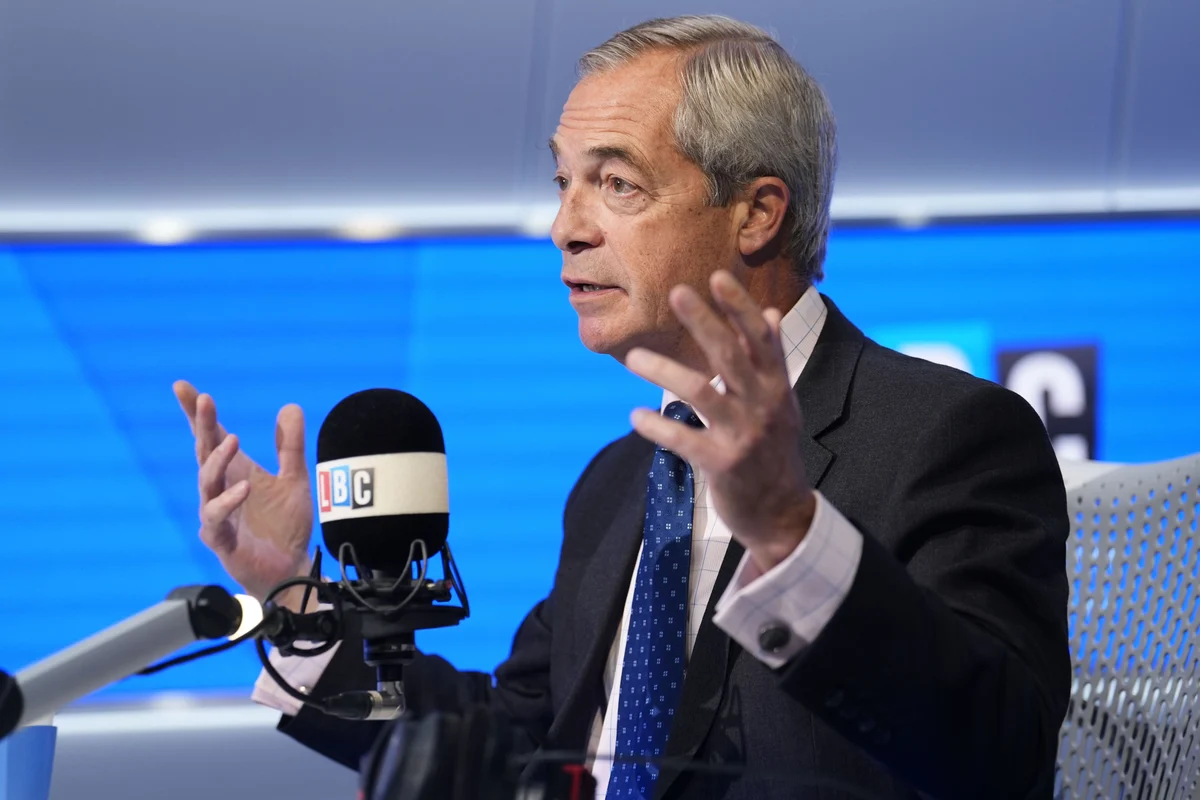

Civility obsessives love a silver-tongued devil, wearing a nice suit, sporting a tidy haircut, while whispering sweet bigotries. The conservatives among them push for marginalized people to lose their rights and freedoms and, sometimes, even risk their lives. They will tolerate a protest but only if you congregate in an orderly fashion, for culturally sanctioned causes, and if you don’t raise your voice or express anger or overstay your welcome.

Within this framework, incivility is refusing to surrender to hatred, refusing to smile politely at someone who doesn’t consider you their equal, refusing to carve away the seemingly unpalatable parts of yourself until there is nothing left. To be uncivil means pointing out hypocrisies and misinformation. It means accurately acknowledging what people have said, with ample documentation and holding them accountable for their words and deeds.

It means protesting injustice while recognizing that protest isn’t supposed to be demure or mindful. It means exercising one’s constitutionally protected right to free speech. It means believing in science and factual information and public education and other such heretical ideas. Civility is a cage that we’re supposed to lock ourselves into and then we are expected to be grateful for our incarceration.

And the notion of two groups— civil and not — is predicated on the idea that we’re all playing by the same rules, and we’re standing on equal footing, untroubled by the inequities and bigotries of the world. As I said, civility is a fantasy, because our political discourse never happens in a vacuum. It happens in the beautiful mess of the real world. It is naïve, at best, to believe civility is more important than who we are, what we stand for and how.

The Trump administration does not have subtle ambitions. Whether it is renaming the Department of Defense the Department of War or gesturing broadly toward “leftists” as “domestic terrorists,” the administration makes clear that there are enemies and allies; there is an us and a them. You are either with them or you are in trouble.

Whatever political norms may have once existed have been shattered time and time again since the beginning of the second Trump presidency. In this new abnormal, we can only gape, with incredulity, at the many ways in which our democracy is being torn asunder — the undue influence of billionaires, the dismantling of vital government programs, the relentless pursuit of undocumented immigrants and ensuing incarceration in inhumane facilities and an ever-growing list of other, uniquely American horrors. But to speak these truths is uncivil, impolite, un-American. To speak these truths means you are one of them, outside the protection of the leaders of this country.

The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis is a testament to the stark contrast between civility and incivility. We think we know a lot about the civil rights movement and many of us do, but we often forget the sheer, unending violence of institutionalized racism by way of Jim Crow. White people of that era wielded power with impunity. They sprayed protesters with fire hoses and tear gas. They sicced dogs on them. They resorted to all manner of physical and stochastic violence. And sometimes, things escalated further.

In one of the museum’s exhibits, there is the mangled, incinerated husk of a Greyhound bus that carried Freedom Riders in Alabama. It was firebombed by a mob of angry white people who then beat the Freedom Riders as they escaped the burning bus. The Riders were fighting to bring attention to the ravages of Jim Crow. Protesters at sit-ins were using their power to demand their rightful place in a free society. All of their protest was civil and nonviolent.

Nonviolence didn’t mean passivity. It was a strategy, intended to reveal the brutal contrast between the tactics of the oppressor and the experiences of the oppressed. Nonviolent, civil protest was met with rank incivility, which is to say that the hypocritical way in which we presently understand civility and incivility is nothing new.

Calling for civility is about exerting power. It is a way of reminding the powerless that they exist at the will of those in power and should act accordingly. It is a demand for control.

Civility is wielded as a cudgel to further clarify the differences between “us” and “them.” It is the demand of people with thin skin who don’t want their delicate egos and impoverished ideas challenged. And it is a tool of fearful leaders, clinging to power with desperate, sweaty hands, thrilled at the ways they are forcing people, corporations and even other nations to bend to their will but terrified at what will happen when it all slips away.

As a writer, as a person, I do not know how to live and write and thrive in a world where working for decency and fairness and equity can be seen as incivility, where it can result in threats on my life, or those of my family; where I worry about a rogue Supreme Court trying to legally nullify my marriage; where I worry about my neighbors and community who are vulnerable to unchecked power. I worry and I worry and I worry and I feel helpless and angry and tired but also recognize that doing nothing is not an acceptable choice.

Every single day, I read the news, and I can hardly process it all. I keep wondering when we will reach a cultural breaking point, when finally, the Trump administration will go far enough to shove us out of the comforts of our day-to-day lives. I look at our elected leaders, especially the Democratic ones, and hardly recognize them. I’ve written, many times, about how no one is coming to save us, but I never imagined that our leaders would agree, that they would comply with so much in advance, that they would rely as a political strategy more on embracing conservative policies than standing up for progressive ones.

At a recent dress rehearsal for the opera “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay,” adapted from Michael Chabon’s novel of the same name, I was struck by the parallels between the story and our present day — the despair of enduring fascism, the sufferance of living a lie out of fear, the necessity of resistances great and small and the salvation of storytelling. When Joe Kavalier is off to war, fighting the Axis powers, his estranged girlfriend, Rosa Saks, writes him a letter, imploring him to come home and invoking the Hebrew concept of tikkun olam: The world will always be broken, she sings. Repair it anyway.

I have not been able to get those words out of my head. We are at such a dangerous and delicate moment in American history. The onus is on all of us to reject the fantasy of civility in favor of repair. This country is broken, but that need not be permanent.