Opinion | Beyond Caricature: Why The ‘South Asian Capitalism’ Poster Fails India & Scholarship

By Gopal Goswami,News18

Copyright news18

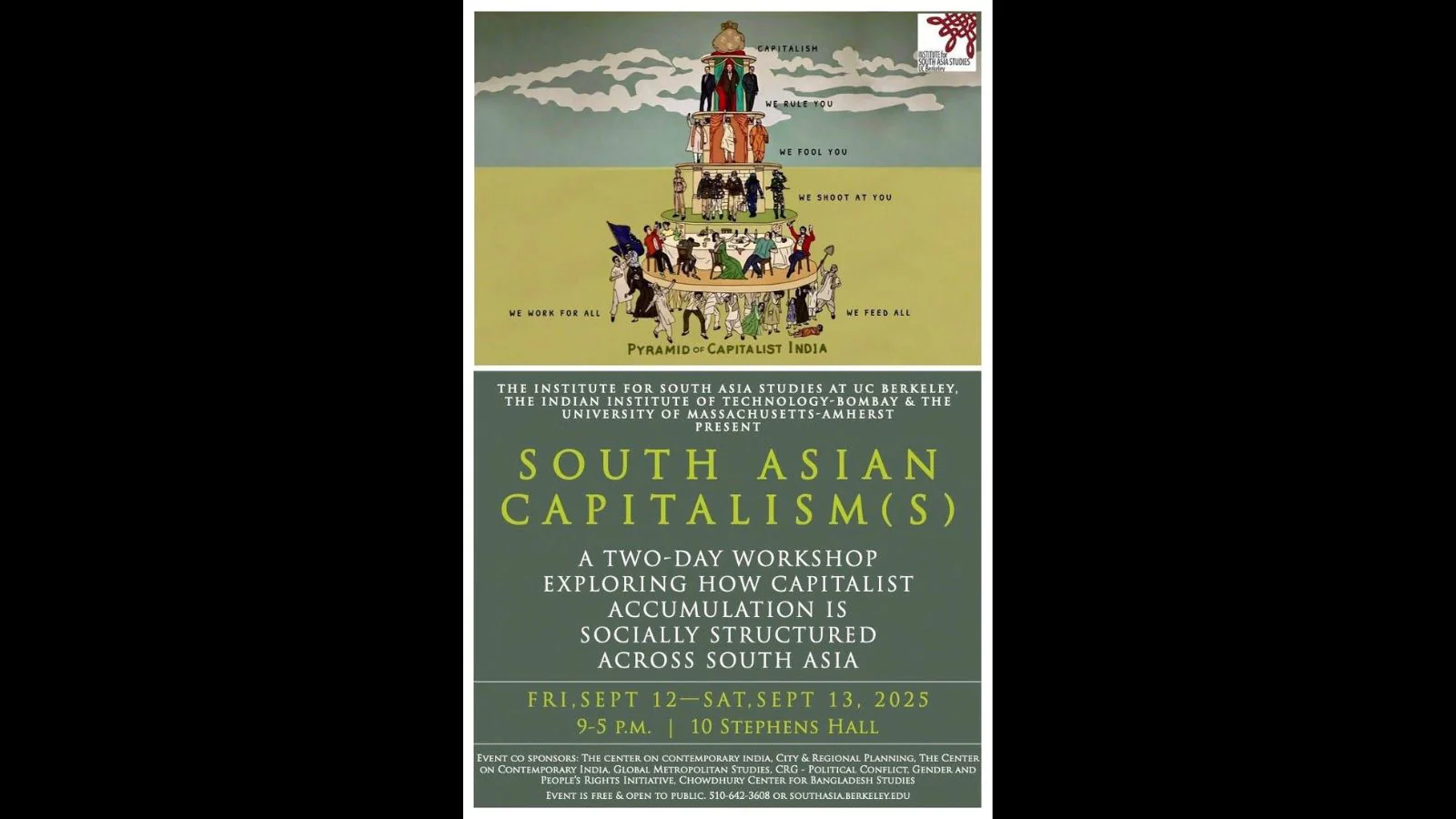

In recent weeks, a poster promoting an academic workshop titled ‘South Asian Capitalism(s)’, jointly organised by UC Berkeley, IIT-Bombay, and UMass Amherst, has sparked a firestorm of controversy. The event’s stated aim is to explore how “capitalist accumulation is socially structured across South Asia”. A worthy and timely topic. But the visual framing of this discussion undermines its credibility. By uncritically importing a European class pyramid, and by populating the top layers with distinctly Hindu imagery, the poster does more than miscommunicate; it distorts history, revives colonial stereotypes, and fuels religious bias.

To understand why this is deeply problematic, we must examine three interlinked issues: the mismatch of frameworks, the selective targeting of Hindu symbols, and the erasure of indigenous socio-economic thought.

Mismatch of Frameworks: Western Pyramid For An Eastern Tapestry

The most prominent element of the poster is the classic “Pyramid of Capitalist System”. This cartoon first appeared in late 19th-century Europe, reflecting the Marxist critique of industrial capitalism:

•At the base: workers and peasants, “We feed all.”

•Above them: military and clergy, “We shoot you,” “We fool you.”

•At the top: capitalists, “We rule you,” and finally, “We eat for you.”

This image emerged in a very specific historical context, rapid industrialisation, the rise of factory labour, the dominance of a capitalist bourgeoisie, and the church’s role as a legitimising force.

To transplant this pyramid wholesale onto South Asia is intellectually lazy.

South Asia’s social and economic history cannot be flattened into European categories of “proletariat”, “bourgeoisie”, and “clergy”. India’s lived realities have always been more layered and localised:

•Village self-governance and guilds (shrenis) coexisted with imperial states.

•The varna system, as described in ancient texts, was meant to be functional and fluid, not a rigid hierarchy by birth.

•Spiritual and economic life were interwoven, with temples often acting as centers of education, charity, and skill development, not merely instruments of control.

As I have argued in my other articles on historical framing, imported conceptual templates risk erasing indigenous complexities. A workshop on ‘South Asian Capitalism(s)’ should be grounded in South Asian sources and frameworks, not merely retrofitted to Western political cartoons.

Selective Targeting of Hindu Imagery

Perhaps the most inflammatory element of the poster is its depiction of the “We Fool You” layer. Here, the figures are unmistakably Hindu in appearance, saffron robes, sacred marks, traditional attire.

The implication is clear: Hindu religious institutions are uniquely responsible for deception and ideological control.

This raises urgent questions:

•Why single out Hinduism in a region that also includes Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Christianity?

•Where are the symbols representing other institutions, colonial missionaries, political parties, secular bureaucracies, Islamic capitalism that have historically shaped belief and power?

This selective framing echoes colonial propaganda, which often portrayed Hindu priests and customs as inherently oppressive to justify foreign “civilising missions”. By visually isolating Hinduism in the role of “fooler”, the poster revives these outdated tropes under the guise of academic critique.

It is vital to distinguish between valid critique and symbolic targeting.

Critique is necessary. Hindu institutions, like all institutions, had moments of exploitation and in past but it has done most reforms, while others are dogmatic. But when a public, internationally visible poster depicts only Hindu symbols, it ceases to be purposefully made to demean Hindu culture and becomes caricature.

Indigenous Economic Thought: The Missing Narrative

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of this poster is what it leaves out. For thousands of years, India has produced sophisticated theories of governance, economics, and ethics. These cannot be shoehorned into European models.

Dharma and Artha: Ethics of Wealth

In Hindu philosophy, Arth (Prosperity) is never isolated from Dharm (ethical duty) and Moksha (liberation). The Bhagavad Gita calls for Nishkama Karm, action without selfish attachment to results.

This principle shaped rulers, merchants, and communities. Wealth was to be pursued responsibly, shared, and never hoarded without purpose.

The Arthashastra and Statecraft

Manu Smriti and Kautilya’s Arthashastra (3rd century BCE) the earliest treatises on statecraft and economics. It prescribes welfare measures such as distribution of wealth, irrigation, disaster relief, and fair taxation, centuries before modern welfare states emerged. According to these Hindu scriptures, Kings are custodians, not owners, of wealth.

Guilds and Local Autonomy

India’s artisan and merchant guilds (Shrenis) functioned as self-regulating bodies:

•Setting quality standards, prices, and apprenticeships.

•Funding temples, schools, and public works.

•Acting as porto-democratic associations within larger kingdoms.

Village Self-Sufficiency

Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of Gram Swaraj was inspired by ancient models of village self-governance. These villages were decentralised economic units where decisions were made collectively, limiting the exploitative concentration of power.

Historical Pluralism: Multiple Stories, Not One Pyramid

The poster’s pyramid suggests a static, top-down oppression.

In reality, Indian history is full of pluralistic and dynamic exchanges:

•The Harappan Civilisation (2500 BCE) shows evidence of urban planning, standardised weights, and egalitarian trade practices.

•During the Mauryan Empire, inscriptions show state support for hospitals, rest houses, and welfare measures.

•The Chola Empire managed maritime trade through democratic assemblies (sabhas), proving governance and commerce could coexist.

•In medieval India, Hindu temples, Jain institutions, and Buddhist monasteries all contributed to education, charity, and art.

No single religious (except Islam) or political group monopolised control across time and space. To depict only one tradition at the “fooling” layer is to erase centuries of diversity and shared responsibility.

Why Visuals Matter: Symbols Shape Narratives

Visuals are powerful medium of expression. They travel faster than academic papers, shaping global perceptions. When a prestigious consortium of institutions uses such a reductive and inflammatory image, the impact is far-reaching:

•International audiences unfamiliar with India may internalise these stereotypes as fact.

•Indian students and scholars may feel alienated or misrepresented.

•Public trust in academia as a neutral space for inquiry is damaged.

Ideological framing, scholarship carries a duty of representation. It must be rigorous, self-critical, and accountable to those it depicts.

The Responsibility of Institutions

The workshop organisers, UC Berkeley, IIT-Bombay, and UMass Amherst, must answer some key questions:

1.Who approved the visual design, and what scholarship informed it?

2.Were diverse voices consulted, including experts on Hindu traditions and South Asian socio-economic history?

3.Why were other religious and political symbols excluded from representation?

A public explanation would not only restore credibility but also model the transparency that academia claims to value.

Towards Better Scholarship: Principles for the Future

This controversy is an opportunity for reflection. If we are to have meaningful discussions about capitalism in South Asia, we must:

•Engage with indigenous sources, from the Manu Smriti, Arthashastra to local oral histories.

•Recognise diversity, region, caste, religion, and gender must all be represented.

•Avoid colonial echoes, critique should not recycle stereotypes once used to justify subjugation.

•Include multiple stakeholders, scholars, communities, and practitioners must have a voice.

Only then can we move beyond caricature to understanding.

Complexity Over Simplification

South Asia is not a pyramid. It is a tapestry woven from countless threads: local economies, spiritual traditions, political experiments, and cultural exchanges. To flatten this richness into a European class cartoon, and to scapegoat one religious tradition in the process, is not scholarship, it is symbolic violence.

Critique is necessary, but it must be fair, historically grounded, and intellectually honest. If the goal is to challenge capitalism, let us do so with tools that reflect our own histories and realities, not borrowed stereotypes that erase them. In the end, the true test of academic integrity is this: to illuminate complexity, not to caricature it.

The author is a researcher, columnist and social thinker. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.