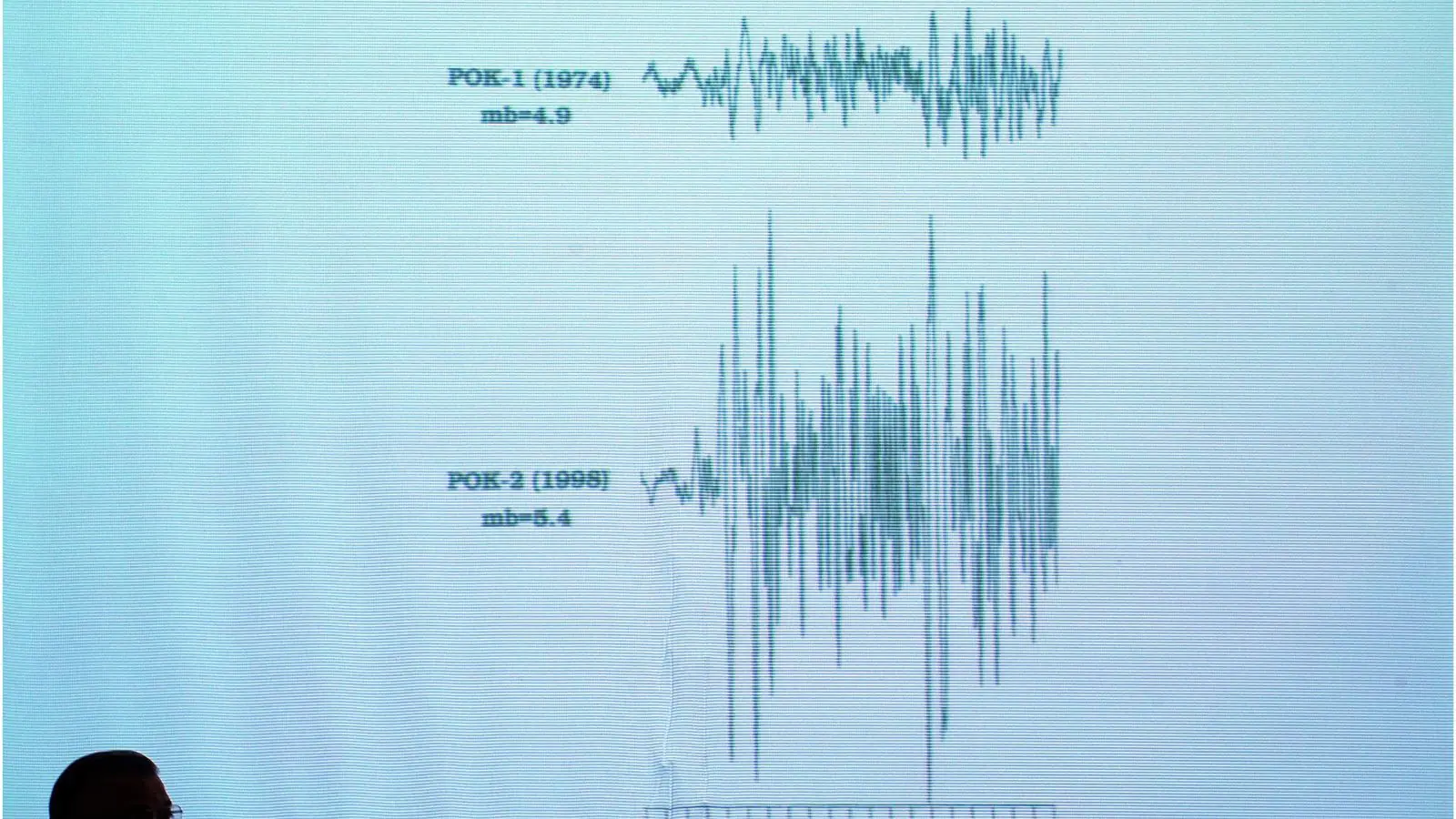

Copyright news18

American President Donald Trump has pulled a skeleton out of Pakistan’s nuclear closet. In an interview to a leading American cable news network, the Don of indiscretion suggested that Pakistan is among a triad of trigger-happy nations still conducting nuclear tests. The claim has caused jaws to drop across the world and came in response to a question on why Donald Trump wants the United States to resume nuclear testing. If he makes a compelling case, his administration could end a 33-year moratorium on American nuclear tests. But beyond optics, it’s unclear what fresh testing achieves other than risking a new nuclear arms race. The US already has enough weapons, in Trump’s own words, “to blow up the world 150 times”. Washington speaks from confidence, having perfected its arsenal after hundreds of tests on US soil and deep in the Pacific. While Trump’s loose nuclear talk, particularly his reference to Pakistan, may serve as domestic political theatre, it carries major implications for India. If Pakistan has indeed been secretly testing nuclear weapons, that is deeply alarming for New Delhi. Unlike China, which has dismissed Trump’s claim as fiction, Islamabad has maintained silence. That silence alone gives India every reason to rethink its current, pacifist nuclear posture. India last tested a nuclear device in the Rajasthan desert in 1998. The global reaction was one of unprecedented hostility. The US and other nations, especially Japan, imposed sweeping sanctions, freezing aid, blocking credit lines, and restricting technology exports. India adapted, but then announced a self-imposed moratorium on nuclear testing. Since then, India has adhered to a doctrine of “credible minimum deterrence” under a no-first-use policy maintaining only the arsenal required to deter Pakistan and China. The problem: if Pakistan is still allegedly testing, and China possesses advanced capabilities such as the Fractional Orbital Bombardment System (FOBS) – which can bypass missile defences – India is at a clear strategic disadvantage. Doubts linger as well over the efficacy of the 1998 Pokhran-II test. In the aftermath, seismic readings from global monitoring stations suggested the combined yield was only 10 to 15 kilotonnes, far below the official claim of 58 kilotonnes. (For context: seismic data measures ground vibrations caused by a nuclear blast; kt = kilotonne, a standard unit of explosive energy.) If accurate, it would mean India’s test underperformed. Whether those doubts were real or exaggerated, they remain unresolved. Which raises the core question: should India continue to rely on an untested deterrent while its adversaries advance unchecked? If the US breaks the moratorium, India has a legitimate opening to test again this time to settle the debate over its true nuclear capability, once and for all.