Copyright The New York Times

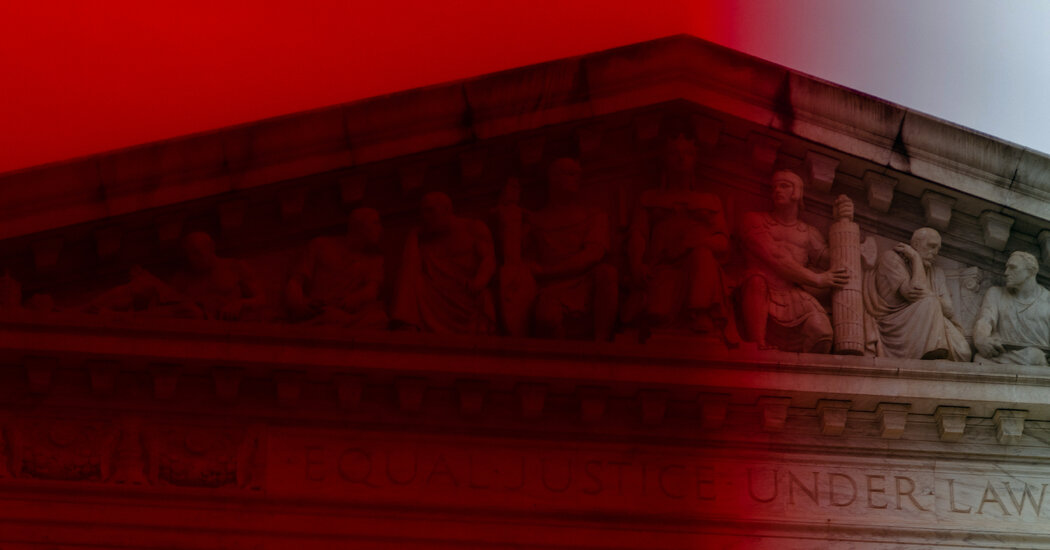

At Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv a few weeks ago, about to fly back to New York, I handed my passport to two young border officers. One of them examined it and handed it to the other with a puzzled expression. Now the second officer looked concerned. “What is your gender?” he asked. “It’s X,” I answered. “What does that mean?” “It means it’s X.” “Can you elaborate?” “No. Is there an issue?” The officers conferred for a minute and sent me on my way. It was glorious. All my life, I have been asked to explain my gender. When I was a little kid, children and adults would interrogate my appearance because I wore pants but my hair was a bit too long for a Soviet boy. As an adult, I would often face questioning when I tried to use a women’s bathroom. Finally, at the age of 58, I was able to refuse to explain my gender to someone with authority, because I carry a U.S. passport that indicates my gender as “X” — an official document that attests to my being exactly who I am: a person who doesn’t identify as either male or female. In another sense, the document attests to the meaninglessness and uselessness of all gender designations. Why did the border officers need to know my gender at all? I match the age indicated in my passport. The photo is mine. New technology makes it close to impossible to travel using a look-alike’s documents; many passports contain iris scans and fingerprints. Perhaps ironically, some of the world’s most repressive states, including contemporary Iran and Communist Poland, have at times made it easy for people to change their official gender designation — or indeed, forced people to do so, bringing identity documents in line with their gender presentation in a strictly binary, heteronormative way. The Soviet Union, where I grew up, made it possible for some people to transition legally, as well as socially and medically, back in the 1970s. This accomplished the state’s goal of keeping everything in familiar order and everyone easily identifiable. In other respects, however, the Soviet classification system was exceptionally rigid. My Soviet domestic documents said that I was Jewish. The Soviet Union had long since collapsed when I tried to change this line in my internal passport to say “citizen of Russia.” I was rebuffed by a low-level bureaucrat, who explained that since both of my parents were Jewish, I had no choice but to keep the entry. This one wasn’t there so much to help the state to accurately identify me as to keep me in a lower position in the nation’s ethnic caste system. State-issued documents aren’t just tools to allow identification; they’re also tools to enforce hierarchies. In his book “The Passport in America,” the historian Craig Robertson argues that the document has served both to affirm and to assign such attributes of identity as class, race and gender. That last category didn’t show up on the U.S. passport until 1976, after a panel of experts convened by the State Department noted that the rise of “unisex attire and hairstyles” had made it harder to determine a person’s sex. “Gender markers thus were born out of the fear that gender was becoming ungovernable,” wrote the immigration attorney Lauren DesRosiers. In the United States, it became possible for people to change the gender markers in their passports soon after passports became mandatory for travel in and out of the country in 1978. The process usually required extensive documentation and often involved the courts. Over the last decade and a half, the process became less cumbersome. The Biden administration allowed Americans to self-declare their genders without supplying additional documentation and added the X option, which many states already allowed on driver’s licenses. On his first day back in office in January, President Trump signed an executive order titled “Defending Women From Gender Ideology, Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government,” which, among other things, directed the State Department to stop issuing passports with the X designation and to stop allowing people to opt for gender markers different from the sex listed on their birth certificates. The American Civil Liberties Union sued. I went to the hearing, at a Federal District Court in Boston. As often happens in cases involving Trump’s policies, the sides were not exactly arguing: They were talking past each other. The A.C.L.U. brought five lawyers; the government had two. The A.C.L.U. argued that traveling with a passport that doesn’t match one’s gender presentation can put a person in danger, especially in countries where transitioning is illegal or stigmatized. The government argued, in effect, that Trump is president and can issue any executive order he wants. In April, the Massachusetts federal judge, Julia E. Kobick, issued a preliminary injunction against the executive order. The government, the judge wrote in a 56-page judgment, “has not substantiated, with evidence or developed argument, its claim that its facially discriminatory policies” served any important purpose. On Thursday, the Supreme Court stayed that ruling, allowing the executive order to go into effect. In a brief unsigned decision, the court said that “displaying passport holders’ sex at birth no more offends equal protection principles than displaying their country of birth — in both cases, the government is merely attesting to a historical fact without subjecting anyone to differential treatment.” Which sounded a lot like the reason that Russian bureaucrat gave for why I couldn’t change my ethnicity designation: a historical fact. As for the people this decision would actually affect — trans and nonbinary people — the court did not see fit to mention them. (“The court nonetheless fails to spill any ink considering the plaintiffs,” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote in her dissent.) The Trump administration’s decision to turn away from an expansive vision of gender, and in particular from recognition of trans people, is not surprising. What is surprising, however, is doing so in a way that makes passports less useful for identifying people as they move through the world. In theory, at least, border guards and police officers should be able to use the gender designation in a document — along with the photo, age, name and other information — to confirm that the person standing in front of them is the document’s rightful holder. If, however, the passport says the person is male but the person does not appear to the officer to be male, the process of confirmation becomes more difficult. But if the new rule weakens passports’ manifest function, it greatly strengthens their other function: as a tool to enforce social hierarchy. The consequences for Americans who travel abroad can be dire. If your appearance does not match your gender presentation, you may be unable to move across borders or board planes. No airline wants to take the risk of transporting people who aren’t who they say they are. A friend who carries the passport of a country where transition is illegal essentially detransitions every time she flies: She dons baggy men’s clothes and hides her long hair under a hat. That is, the only way for her to match her official documents is to wear a disguise. I ask non-trans readers of this column to imagine having to dress and act as the opposite gender every time they travel. This kind of temporary transformation is not always possible, and is never foolproof. In many countries, one’s passport is checked — and often registered with the authorities — at hotels, when entering administrative buildings and even simply when walking in the street. Some airports have sex-segregated security lines. Some train lines operate sex-segregated cars. And then there is travel for work. Journalists, for example, have to present their passports to obtain press credentials. There are places in the world where working with a press pass that says I am “F” would expose me to mortal danger. As the Times editorial board has pointed out, Trump has undertaken a campaign to force trans people out of public life — by executive-ordering us out of existence. The Supreme Court’s decision advances that campaign significantly. The point of the executive order was not to restore “historical facts” but to enforce a gendered social hierarchy and to punish those who do not conform to it.