Copyright news18

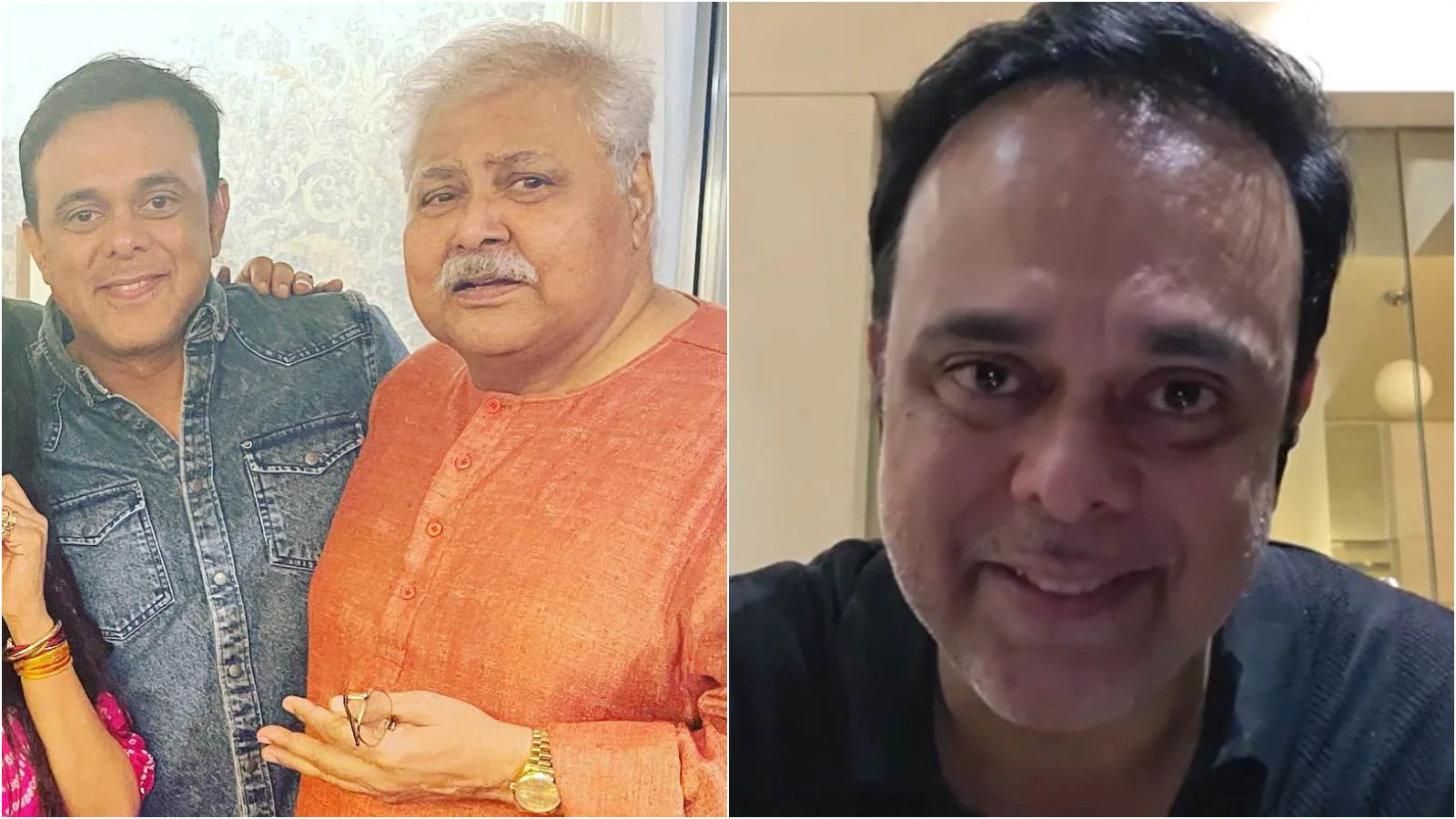

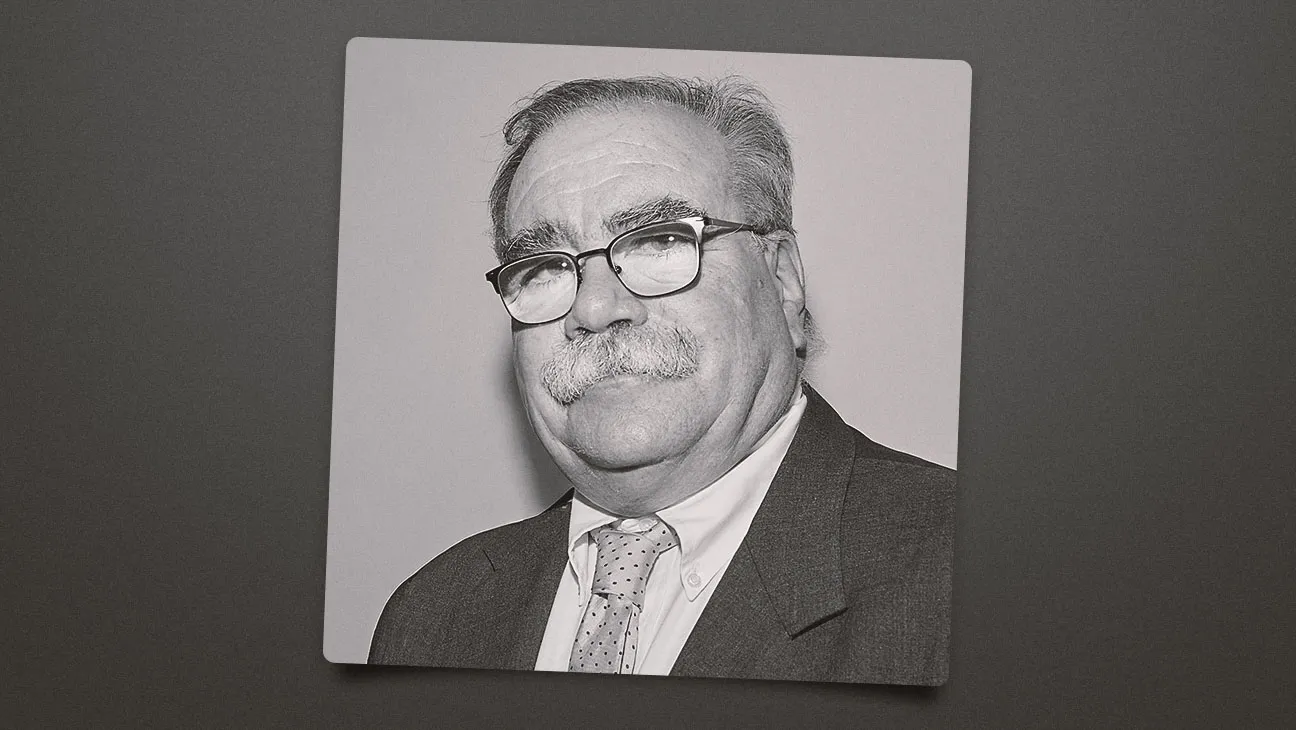

For anyone who grew up in 1980s India, Satish Shah wasn’t just a familiar face – he was the era itself, a reflex, permanently etched into our collective consciousness like a song you never forget. His voice, his half-smile, that perfect pause before a punchline – they became part of the way a generation processed humour, absurdity, and even routine. Shah’s death on October 25 isn’t only the loss of a fine actor; it’s the quiet fade-out of a shared rhythm of laughter that shaped an era. Characteristically, Shah began in a very different corner of cinema – serious, introspective, and miles away from the comic brilliance that would define him. When he first appeared in Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastaan (1978) and later in Gaman (1978), Umrao Jaan (1981), Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai (1980) and Saath Saath (1982), he was part of that second wave of parallel cinema that blurred the lines between art and entertainment. Even Ramesh Sippy spotted the edge beneath the geniality. In Shakti (1982), Shah played the meanest of four men who molest Smita Patil on a train, only to be beaten to a pulp by Amitabh Bachchan. It was a startling introduction – intense, raw, and far removed from the gentle comedian he would later become. Shah arrived as part of the new wave of the 1980s, trained and prepared actors who would redefine what separated a ‘star’ from an ‘actor.’ He was as talented as any of his contemporaries, arguably more so in many cases, but he found his calling in comedy. And what a calling it was. Where others (read critics) might have lamented typecasting, Shah transformed it into an art form. He became one of Hindi cinema’s most organic funny men, never resorting to theatrics or cheap gimmicks. He didn’t need body humour or double entendres – he kept it real. Sometimes, he would simply react to a regular situation, and that reaction alone was worth a million laughs. His genius lay in seeing the absurdity in the everyday and reflecting it back to us with perfect timing. In the 1980s – a decade when India discovered laughter as social commentary, and Satish Shah became its face. Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (1983) turned moral chaos into a farce and elevated Shah to cult status; it was the kind of satire that stayed relevant precisely because he played it straight. But it was television where Satish Shah truly became a household fixture. Around the same time, Yeh Jo Hai Zindagi (1984) arrived on Doordarshan. Every Friday, Shah played a different character – each so distinct and lived-in that you forgot they were all him. As television grew up, so did he. The 1990s found him everywhere the medium was reinventing itself – in Filmi Chakkar (1996), where he played the patriarch of a movie-mad family, and on Phillips Top 10 (1994), where he hosted India’s favourite countdown show. Imagine the cultural bandwidth of the time: Shah discussing chartbusters with Randy “Macho Man” Savage in one episode, then spoofing filmy clichés the next week. And when Indian television wanted to escape the suffocating grip of saas-bahu soap operas in the 2000s, Shah was at the vanguard once again with Sarabhai vs Sarabhai (2004), proving that intelligent, restrained comedy could find an audience. The show turned urbane sarcasm into a family value. His character, ‘Indravadan’, became the post-liberalisation successful businessman who laughed at what surrounded him, and at times, himself, before the rest of the country could. Beyond these landmark shows, Shah wove himself into the fabric of Hindi cinema across three decades. He worked with nearly every leading man of his time – from Naseeruddin Shah and Rishi Kapoor to Aamir Khan, Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan, and Hrithik Roshan. He appeared in perhaps every newsworthy film that wasn’t always pathbreaking but that wasn’t the point. Shah was a conscious part of every leading man’s universe, the reliable presence who could elevate any scene he inhabited. In the 1980s it was Malamaal, Peecha Karo, Khoj; in the 1990s, Haatimtai, Narasimha, Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa, Hum Aapke Hain Koun!, Saajan Chale Sasuraal, Judwaa; in the 2000s, Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai, Sandwich, Om Shanti Om. None of these titles alone define either him or the zeitgeist, yet together they prove an odd truth – Satish Shah’s presence stitched the industry’s generations together. He was, quite literally, the common man in every superstar’s universe. What kept him singular was restraint. Where others performed comedy, he inhabited it. He never needed double entendres or exaggerated expressions; a raised eyebrow, a murmured aside, a blink too long could detonate a scene. His humour was observational – drawn from the way Indians actually speak, worry, and dream. Even when typecast, he refused to become lazy about it. After the fiasco of Humshakals (2014), he decided he’d had enough of the circus and walked away. It was an exit of dignity from a man who understood that silence can be a better punchline than noise. But like any good actor, Shah’s range, too, went far beyond laughter. In Saathiya (2002), playing the sceptical father of Vivek Oberoi’s character, he distilled the Indian middle-class ego in one line about every house looking alike – a throwaway remark loaded with class privilege and unintentional cruelty. Few performers could make hypocrisy so believable. In Stuntman (1994), he famously upstaged Jackie Shroff in the dance number ‘Amma dekh’, and in Maalamaal (1988) he left even Naseeruddin Shah looking mildly bewildered by his spontaneity. For all his roles, what endures is the tone he set – gentle irreverence. Satish Shah taught an entire generation that humour need not be at someone’s expense; that being funny and being kind weren’t opposites. His face became shorthand for the safe space between sarcasm and empathy. Today, his scenes from Yeh Jo Hai Zindagi, Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro, Main Hoon Na, Sarabhai vs Sarabhai loop endlessly on Instagram and YouTube – proof that his timing still syncs with ours, decades later. Today, as we say goodbye to Satish Shah, we mourn a piece of our own history. He made us laugh without asking us to check our intelligence at the door. He was there for every transition, every evolution of Indian entertainment, always relevant, always welcome. For those who grew up watching him, his face, his timing, his warmth – these aren’t just memories. They’re home. (The writer is a film historian. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views)