Copyright Polygon

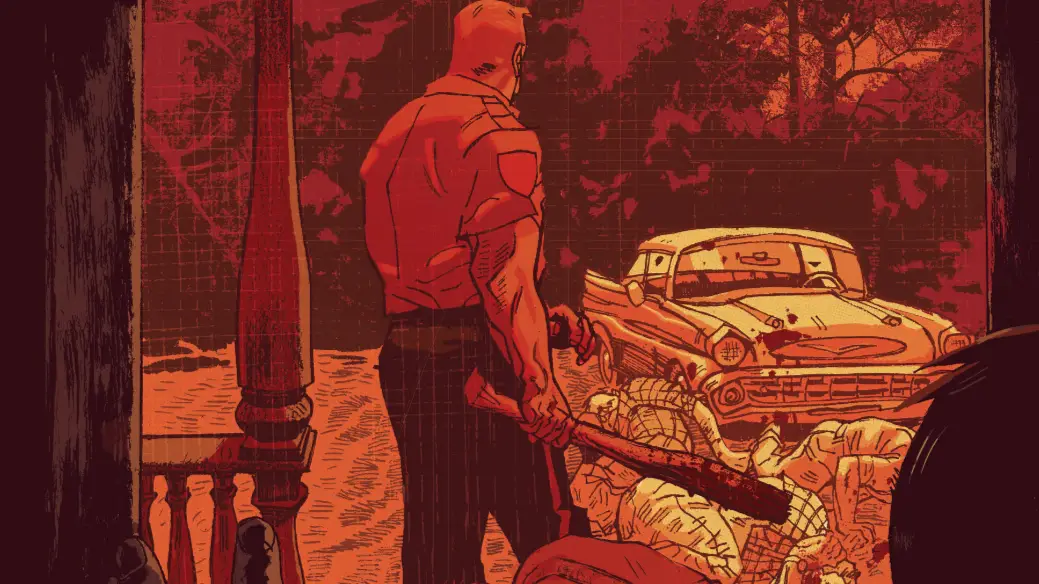

From ages 13 to 18, I lived in North Carolina. Coming from New York, I was very much an outsider when I first arrived. It was a culture clash, to say the least, and I often got into trouble for things I never would have back home — like advocating for myself or expressing independent thoughts. I knew I didn’t belong because I was taught to feel that way. Underneath all the kind dispositions and Southern hospitality was a prejudice I had never encountered before or after, and when I moved back North after high school, I never looked back. No story captures that experience for me quite like Jason Aaron and Jason Latour’s Southern Bastards. Though set in the fictional Craw County, loosely inspired by an unincorporated community in Russell County, Alabama, the town feels alive, a character all its own. Much like the titular town in HBO’s It: Welcome to Derry, Craw County is a small county with a dark heart, where cruelty isn’t just tolerated — it’s tradition. The “good” folks stay silent, complicit by choice, and righteousness has no foothold against the weight of old, entrenched ways. Southern Bastards is a raw, self-contained story that speaks to the times, now headed for a live-action adaptation at Hulu from writers and executive producers Bill Dubuque (Ozark, The Accountant) and Nia DaCosta (Candyman, The Marvels). Southern Bastards remains one of the greatest unfinished comics, its run cut short at issue #20 after allegations against co-creator Jason Latour halted production. Yet even without a proper conclusion (and without downplaying those allegations), it’s absolutely worth reading. The series offers a sharp, unflinching look at how small-town mindsets operate, and more importantly, showcases how those same sensibilities have seeped into mainstream culture today. Southern Bastards follows Earl Tubb, an aging Vietnam veteran who returns to his Alabama hometown to settle his late father’s affairs, only to find it ruled by a corrupt high school football coach named Boss. What begins as a story about a man confronting his past spirals into a brutal exploration of small-town power, generational curses, and the violent legacy of Southern pride. Earl’s arc perfectly sets the tone for a story built around perpetual cycles of cruelty. As a young man, Earl despised his father and used the Vietnam War as an excuse to escape both the man and the town he loathed. However, a lifetime of running from his problems became his defining trait. When Early finally returns home 40 years later, he realizes the town has become worse than ever. His father, once the county sheriff, was a local legend known for using a stick to subdue criminals. But four decades later, Boss Coach and his corruption have taken over, and a new generation of high school students has become henchmen, enforcing violent rule. Earl witnesses this first-hand when his old friend is nearly beaten to death, pushing him to channel his own turmoil into a fight against Craw County. Southern Bastards reaches one of my favorite comic reveals at the end of issue #4, a moment that should stay under wraps as the show’s promotions begin. It has the weight of a Game of Thrones twist, immediately signaling a new narrative direction. For those who are familiar with the plot, it’s clear why Nia DaCosta was chosen as executive producer. The comic tackles racial issues rooted in its rugged Southern setting, and a key narrative shift shows exactly why Earl worried about repeating his father’s mistakes. DaCosta has also proven herself skillful in handling community-focused stories, having delved into the history of Chicago’s Cabrini-Green in Candyman (2021). At the end of the first issue, Jason Aaron admits in the letters column, “I love the South, but the South also scares the living shit out of me.” That sentiment perfectly captures what Southern Bastards embodies: the raw, unsettling reality of the South, both in its beauty and its darkness. “The south is more peaceful than any other place I’ve ever been, but more primal too,” Aaron continues. “More timeless but more haunted. More spiritual. More hateful. More beautiful. More scarred.” Southern Bastards exposes the moral decay through the lens of a small southern town — how those in power manipulate others, how personal connections and obligations entangle everyone, and how the veneer of tradition conceals a far more complex reality. Football, good cooking, and the slow rhythms of Southern life may seem idyllic, but beneath them lies a disturbing undercurrent, especially resonant in a modern-day culture that sometimes romanticizes a past shaped by outdated ways of thinking. The attitudes and behaviors, largely left behind in other parts of America, still linger in the South. It’s striking that a story centered on a small town can feel like a timely reflection of the broader United States, even a decade after its debut. Perhaps it simply took the rest of the country some time to catch up to a reality the South has never really left behind.