Copyright HuffPost

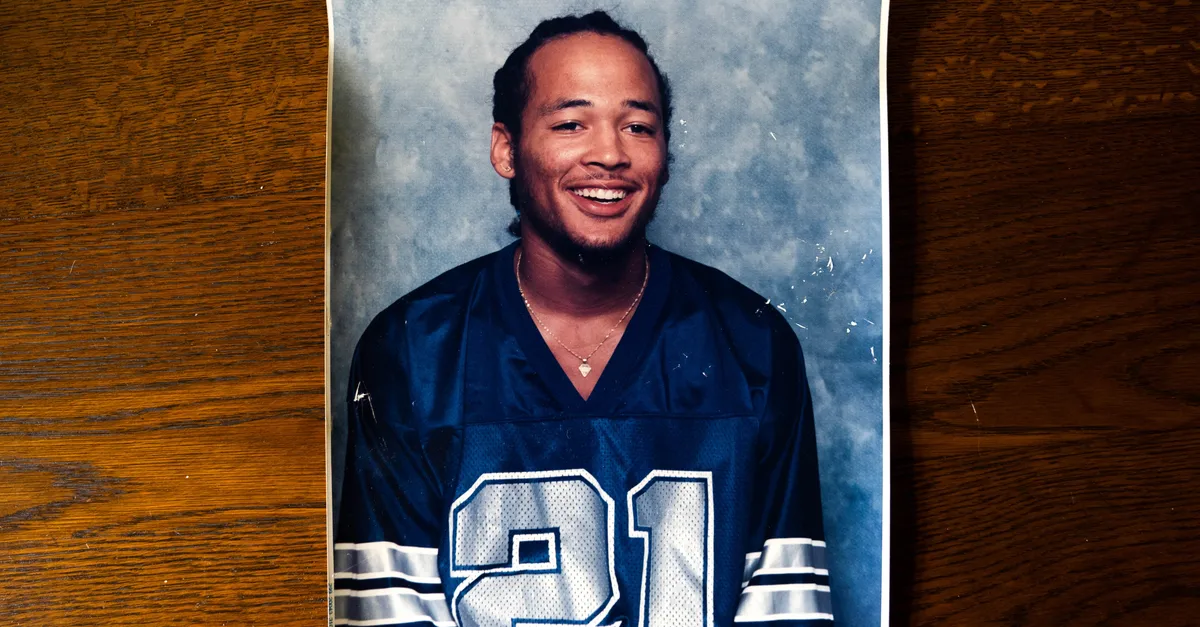

MCALESTER, Okla. — Oklahoma’s top prosecutor wanted to make sure a man who was never proven to have killed anyone would be executed by the state. And so, on a Tuesday afternoon in July, he sent a secret message to a judge, asking for some help. “I have an active investigation issue that I wish to address with you,” Gentner Drummond, the state’s attorney general, began his email. The recipient was Gary Lumpkin, the top judge on Oklahoma’s Criminal Court of Appeals. The subject line misspelled the name of the man on death row, Tremane Wood. Advertisement It was a tricky case for Drummond, who had cultivated a reputation as a fair arbiter of capital punishment. The death penalty is supposedly reserved for the “worst-of-the-worst” kind of criminals, but Tremane was never a particularly compelling example. In 2002, Tremane, his older brother and two women were charged with first-degree murder for killing Ronnie Wipf during a botched robbery. Wipf died from a single stab wound, but under the state’s so-called felony murder statute, prosecutors didn’t have to prove who killed him in order to secure murder convictions — only that they each participated in the robbery that led to the death. Tremane denied stabbing Wipf. He was represented at trial by a lawyer struggling with drug addiction who billed almost no work on the case, and Tremane was sentenced to death. His older brother, who testified that he had killed Wipf, had robust legal representation and received a life sentence. The outcome seemed perverse on its face: The person who admitted to the murder received a more lenient sentence than his little brother, who swore he had never killed anyone. Even some of the people who helped convict Tremane came to feel that something had gone wrong. The jury foreperson, the only Black member of the jury, has said she felt pressured into voting for death and would have held out for life if she had had more information about the case. The state’s star witness, who is also the mother of Tremane’s eldest son, told HuffPost she doesn’t want Tremane to die. So did the surviving victim of the robbery, as well as the mother of the man who was killed. Advertisement Seemingly, the person most intent on killing Tremane is the state’s attorney general. Drummond had previously asked the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (OCCA) to set Tremane’s execution for Sept. 11, which would have required the state to hold a clemency hearing ahead of time. At that hearing, Tremane and his lawyers would have the chance to make the case for mercy and ask the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board to recommend that the governor spare his life. Maybe the manifest unfairness of the sentences would capture national sympathies and pressure the state to back down from the execution. So Drummond — who is running to become the state’s governor as a tough-on-crime attorney general — came up with a plan that could sabotage Tremane’s chances of clemency. To pull it off, he wanted help from Lumpkin, the judge who was overseeing the case. He explained in the email, which was recently unsealed in a court filing, what he needed and then signed off: “Thank you in advance for your indulgence in this request.” Advertisement The attorney general’s attempt to enlist help from the judge overseeing Tremane’s case to clear the way for his execution is a major blow in a case that was already emblematic of the systemic unfairness in how the criminal justice system determines who deserves to be killed by the state. As HuffPost chronicled in detail in a previous feature, Tremane’s case is marked by allegations that his death sentence was the result of both his severely impaired trial lawyer and prosecutors who played dirty. Despite the common belief that the lengthy appeals process in capital cases ensures that constitutional violations at trial will be rectified before the execution date, Tremane has been denied relief at every turn. In the final days ahead of Tremane’s scheduled execution — including as recently as this week — additional details have emerged exposing how Oklahoma’s prosecutors and judges have coordinated in ways that have undermined Tremane’s final chances at a meaningful review of his case. Drummond’s press secretary Leslie Berger declined to respond to a list of questions about his handling of Tremane’s case, citing an “investigation” into Tremane, although she declined to specify who is conducting the investigation. Asked if Tremane fit the description of the “worst-of-the-worst” criminals the death penalty is supposedly reserved for, Berger wrote, he “was found guilty by a jury and sentenced to death.” She asserted that he had a fair trial. Advertisement Lumpkin did not respond to requests for comment. As it stands, Tremane faces an execution date of Nov. 13. On Thursday, he asked the Supreme Court to stay his execution and review his allegations of prosecutorial misconduct. He has been locked in solitary confinement since June, where he is not allowed contact visits. Unless the prison reverses course, he may never hug his loved ones again. Tremane’s earliest memories are of his father, a cop, beating his mother. When Tremane and his two older brothers tried to protect their mom, their dad beat them, too. Advertisement “He has beaten me to the point where you couldn’t even tell what I looked like, knocked my teeth out, broke my nose, broke my bones, and then wouldn’t let me even get any medical help,” Tremane’s mom, Linda Wood, previously told HuffPost. Tremane’s father, who died in 2012, admitted in court to whipping his sons “like a normal father would,” pushing Linda one time and handcuffing her to a car another time. But he denied that he was abusive. Tremane idolized his older brother Zjaiton “Jake” Wood, their mother told a social worker in 1994. “He would die for Jake,” she said. Advertisement “I’ve never seen anyone be that loyal to a person,” their eldest brother, Andre Wood, said in an interview last year. “Tremane would follow Jake to the end of the Earth. Tremane just loved his brother. And Jake loved Tremane. And there was nothing that could break that. Nothing.” Following Jake’s lead, Tremane joined a gang and fell into the juvenile detention system as a young teen. In late 2001, Jake returned home after spending seven years in prison. By then, Tremane, 22, had two kids and a job at a pizza restaurant in Oklahoma City. He was focused on staying out of trouble. On New Year’s Eve, Tremane was at a house party with his cousins when Jake showed up and told Tremane to come with him. Eager to spend time with his brother after years apart, Tremane agreed. They went to a brewery with Jake’s girlfriend, Lanita Bateman, and Tremane’s ex-girlfriend, Brandy Warden. Advertisement There, the women were approached by two out-of-towners named Ronnie Wipf and Arnold Kleinsasser, who were passing through Oklahoma on their way back to work on a harvest crew. Ronnie suggested the four of them go back to a motel room. Brandy and Lanita didn’t want to go, they would later say, but felt pressure from Jake and Tremane to get money from the unsuspecting men. At the motel room, the group negotiated a price of $210 in exchange for sex. Lanita discreetly gave Jake the motel room number, hoping she and Brandy could escape without having sex and get picked up by the brothers. But before they got that far, two masked men in long trench coats and leather gloves knocked on the door. When Ronnie opened the door, the men burst into the room, and the girls ran out. A struggle ensued. Arnold managed to escape, but Ronnie was fatally stabbed. Within days, Tremane, Jake, Brandy and Lanita were all arrested and charged with first-degree felony-murder, robbery with firearms, and conspiracy to commit robbery with a dangerous weapon. Prosecutors sought lengthy prison sentences for the women and death sentences for both brothers. Advertisement The young women faced an impossible decision: help send people they cared for deeply to death row or risk spending the rest of their lives in prison. Lanita, 19, who had only been dating Jake for two months, declined to cooperate with the state and was sentenced to life in prison, plus 101 years. Brandy, 20, who had known Tremane since they were kids, agreed to testify for the state in exchange for a reduced sentence. She had three young children, including a son with Tremane, to get home to. Conflict-of-interest restrictions prevented the Oklahoma Indigent Defense System from representing both Wood brothers, so the court assigned Tremane’s case to private attorney Johnny Albert. Once a respected criminal defense attorney, Albert struggled with drug addiction by the time he took on Tremane’s case and would later temporarily lose his law license due to allegations of client neglect. He billed just two hours of work on the case outside of court and never visited his client in jail. He failed to present evidence that Tremane was not the killer and that his abusive childhood warranted leniency at sentencing. Watching the trial unfold was torture, Andre said. “I’m sitting there, looking at my mom, going, ‘This is the fucking lawyer?’” Andre previously told HuffPost. “I wanted to get up and say, ‘Can I represent my brother? Because this asshole has no clue what he’s doing.’ You can just tell the guy was out of it. I mean, I’ve seen fucked-up people. This lawyer was fucked-up.” Advertisement With Albert failing to mount a meaningful defense for Tremane, Jake made the highly unusual decision to testify in his brother’s trial ahead of his own. He testified that he stabbed Ronnie and that Tremane wasn’t with him on the night of the robbery. He didn’t want his brother to die for something he didn’t do, he said. Parts of Jake’s testimony lacked credibility. Brandy had already placed Tremane at the motel robbery. But there’s evidence that Jake was telling the truth that he — not Tremane — killed Ronnie. Before Lanita was sentenced, a parole officer prepared a report documenting her recollection of the crime. In the report, she describes hearing Jake say that “he thought he killed a guy” after they got home from the motel. This report was available at the time of Tremane’s trial, but Albert never presented it to jurors. Had Albert asked, Lanita would have been willing to testify in support of Tremane, she wrote in a 2011 declaration. Advertisement Lanita doesn’t regret not testifying for the state, even though she may spend the rest of her life in prison. “I can be free no matter where my body is. They can’t lock up my spirit,” she said in a recent interview. “I would not help kill someone.” Tremane’s looming execution has made her feel “helpless,” she said. “I’m devastated. I’m dying inside.” “Trying to save somebody and you can’t do anything but sit and wait and hope that people make the right decisions — it’s painful,” Lanita said. Although the state didn’t have to prove Tremane killed Ronnie in order for jurors to convict, prosecutors portrayed him as an unrepentant killer while making the case that he deserved the ultimate punishment. Advertisement “This person stuck a big knife into the chest of a 19-year-old man. Stuck it in there five inches. And never said to one person, ‘I’m sorry about that,’” Oklahoma County Assistant District Attorney Fern Smith said. “What kind of person is that? Somebody different from you and me. And that fact … is the reason why he deserves the death penalty,” Smith said. “How can you kill, intentionally, knowingly kill another human being and not be sorry about it?” Tremane was convicted and sentenced to death. In Jake’s trial the following year, prosecutors flipped their theory of the crime and portrayed Jake as the killer. They introduced his testimony from Tremane’s trial and letters allegedly written by Jake to Brandy and Smith, the prosecutor, bragging about the killing and threatening more violence. Advertisement “You have evidence from the defendant’s mouth that … that he did in fact murder Ronnie Wipf,” Smith said. “You also have some letters where he, himself, said he murdered Ronnie Wipf. Not only did he murder Ronnie Wipf, he liked it. He enjoyed it.” Initially, Jake wanted to join his brother on death row. But his attorneys worked hard to win his trust and convince him to participate in a vigorous defense. Jurors found Jake guilty of felony murder — but this time, they voted to let him live. Jake was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Advertisement Two years after Tremane’s trial, Albert was arrested after repeatedly failing to show up in court for another case. The lawyer admitted he was struggling with substance abuse and was released on bond to begin drug and alcohol treatment. The Oklahoma Bar Association charged him with 11 counts of professional misconduct based on complaints of neglect from his former clients. Albert admitted to the allegations, and his law license was suspended for 14 months. Two of Albert’s former clients in separate cases have had their death sentences thrown out on the basis of ineffective assistance of counsel. Before he died in 2018, Albert admitted in two separate sworn statements to doing a poor job on Tremane’s case. He also wrote Tremane an apology note, stating, “I’m sorry for everything in the past. You got me at a bad time and its not your fault.” (He, too, misspelled Tremane’s name.) But Tremane’s requests for a new trial had repeatedly been denied by appellate courts, largely for procedural technicalities. Advertisement The trial judge in Tremane’s case rejected his bid for a new trial, finding that Albert’s actions were part of the trial strategy. Even after Albert said that wasn’t the case, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals denied Tremane’s petition for post-conviction relief, finding that Albert’s “client neglect, abuse of drugs and alcohol and emotional instability” appeared to have started after Tremane’s trial had ended. Years later, multiple people who were part of a gang called the Playboy Gangsta Crips provided Tremane’s legal team with sworn affidavits detailing how Albert represented members of the gang in exchange for drugs. The former clients described seeing Albert drink and do drugs regularly before and throughout the period of time he represented Tremane. But that still wasn’t enough for the court. Presented with this evidence, the OCCA again denied Tremane’s petition, stating it was “identical” to his previous claim of ineffective assistance of counsel and that he should have presented this evidence when he first filed for relief. Advertisement “I’m not asking to go home,” Tremane said in an interview last year. “I just want a fair trial with a competent lawyer.” In 2019, shortly after Tremane became eligible for execution, Jake died by suicide in his cell. Tremane could never make sense of how his brother, the strongest person he knew, could kill himself. Some members of his family still doubt the cause of his death. But spending months in solitary confinement himself, Tremane understands how his brother lost the will to live, he said when I visited him in August. “I see what the isolation does to your mind.” The day before the visit, Tremane’s mom told me that he has a strong mindset — but that he was tired. He kept fighting to live, he told her, because he worried about what would happen to her if he died. Advertisement “I’ve tried to play that scenario in my head a million times, and I can’t,” Linda said in an interview. “When I think about him dying, I can’t breathe. I still grieve my son Jake every day because losing your child is not something you ever get over. I wouldn’t wish it on the person I hate most in the world. But to lose two sons, I don’t know. I don’t know how people go on,” she said through tears. “I can’t tell him, ‘Son, if you die, don’t worry, I’ll be alright.’ Because I won’t. I won’t ever be alright,” she said. Advertisement Linda has never met Ronnie’s mother, Barbara Wipf, but she suspects Barbara never recovered from losing her son. “My heart aches for her. And I know there’s nothing I could ever say or ever do that could bring her any peace.” After Ronnie’s death, Barbara fell into a deep depression, she said. It never went away, but with the help of medication, she found a way to cope. “Sometimes all you can do is get it out of the system,” Barbara said in an interview, the lingering pain still audible in her soft voice. “You cry and cry and cry. And then, you feel a little better.” Years after Ronnie’s death, Barbara’s daughter, her only other child, died unexpectedly. “I guess God doesn’t give you too much to bear. He helps you carry everything. We have to believe that there is a God,” she said. Advertisement When Barbara sees Ronnie’s friends getting married and having kids, she thinks about what a good dad he would’ve been. She asked me questions about Tremane and his family. If she resented that Tremane got to have children and grandchildren, and her son didn’t, she didn’t say so. If anything, she sounded sad that Tremane didn’t get to be with them. She told me I could tell Linda that she lost two children, too. Tremane wrote Barbara and her husband a letter last year apologizing for his role in their son’s death. “He wrote me how sorry he is, which I believe, because my religion tells me he wrote the truth,” Barbara said, referring to her Hutterite faith. “I think he should feel sorry.” But she and her husband don’t believe in the death penalty, and she doesn’t want Tremane to die. “They should let him live,” she said. “I don’t think they should execute him.” Advertisement “This will not bring [Ronnie] back,” Barbara continued. “It’s sad, and it will stay sad.” “This will not bring him back ... It’s sad, and it will stay sad.” Earlier this year, Tremane thought he might finally get a chance at a new trial. He had filed his fifth application for postconviction relief, this time arguing that prosecutors lied about the incentives offered to Brandy in exchange for her testimony at trial. The OCCA took the rare step of ordering the trial court to hold an evidentiary hearing to investigate the allegations. When Tremane heard the news, he had a panic attack. Advertisement “I’m used to getting bad news and I know how to deal with that,” he said in the August interview. “I didn’t know what to do with the good news. It’s scary to get your hopes up.” Throughout the trial, prosecutors repeatedly told jurors that Brandy, their star witness, would serve 45 years in prison. The idea that she would be imprisoned into her 60s likely boosted her credibility with jurors because it suggested she wasn’t gaining much by cooperating with the state. “We always felt like we could argue that to the jury. Well, she’s getting life, too, you know?” former Oklahoma County Assistant District Attorney George Burnett said in a procedural interview with the Office of the Attorney General ahead of the evidentiary hearing. In fact, Brandy’s sentence was later modified to 35 years, in exchange for her testifying against her co-defendants — and with “good time” credit, she was released after 12 years. That release date was only possible, Tremane’s lawyers said, because of crucial terms of her deal that were not disclosed to jurors. Advertisement The hearing, which took place over several days in April, yielded explosive revelations. At first, Burnett testified that the prosecution’s plea agreement with Brandy represented the full extent of their deal. Federal public defender Amanda Bass Castro Alves, one of Tremane’s current lawyers, confronted Burnett with evidence that his plea agreement with another witness for the prosecution did not reflect the fact that the prosecutors had dismissed and downgraded the witness’ pending felonies after Tremane was sentenced to death. Burnett then testified that the full scope of the state’s agreement with Brandy was actually documented in a “memorandum,” not in the plea agreement. After learning that neither lawyers for Tremane nor the state had seen the memorandum, the judge obtained a copy from Brandy’s case file at the Oklahoma County Public Defender’s office. It clearly showed, contrary to prosecutors’ claims at Tremane’s trial, that Brandy would receive a sentence of 35 years in exchange for testifying against her co-defendants. Advertisement Asked why Burnett repeatedly told jurors that Brandy would spend 45 years in prison, he testified he “made a mistake, probably.” “Never underestimate my — my ability to say something stupid to a jury,” Burnett said. At the time of Tremane’s trial, Brandy was already serving a deferred felony sentence for an unrelated crime that could be dismissed if she successfully completed probation. After she was charged with felony murder, a probation violation, probation officials filed a report to move forward with her deferred sentence. But the district attorney in that county opted to “hold off,” he wrote in a note on the report. Had Brandy’s deferred felony sentence moved forward, she would not even have been eligible for a sentence modification from 45 to 35 years, Bass Castro Alves wrote in a court filing. Advertisement Not only did this arrangement secretly reduce her sentence, but it also allowed prosecutors to emphasize Brandy’s lack of a felony record to jurors. “The prosecutors’ suppression of their full agreement with Warden undermined [Tremane’s] defense and misled the jury by depriving it of information critical to jurors’ assessment of Warden’s truthfulness, credibility, and motivations for testifying to the story she told the jury,” Bass Castro Alves wrote. “Never underestimate my — my ability to say something stupid to a jury.” Brandy wasn’t involved in discussions around the specifics of her plea deal, she said in an interview. She believed she was agreeing to a deal of 45 years, with the opportunity for review one year after she was sentenced. Her lawyer told her this was the only way to get home to her kids. “It was the first time I felt like I was betraying him. I loved my kids with everything, and I had to choose,” she said. Advertisement Brandy met Tremane when she was about 10 years old, and they dated off and on as teenagers. She loved Tremane, but came to fear Jake, who used intimidation and violence to get his way. When Brandy was about 16, Jake stuck a gun in her mouth and threatened to kill her after she disobeyed his order to stay in the house, she said in an interview. At the time of the trial, she was mad at Tremane for not standing up to his brother, but she has since come to understand how much control Jake exercised over him. The months after the crime were a nightmarish haze. The cops kicked in the door to her sister’s home while Brandy was helping her toddler wipe up after going to the bathroom. She begged the officers to let each of her kids hug her while she sat handcuffed on the couch. Once she was in jail, her father was arrested for an unrelated crime, leaving only her sister to care for her kids. Jail staff put her on suicide watch and prescribed her a high dose of trazodone. “I just felt like a zombie,” she said. Prosecutors were threatening to send her to prison for the rest of her life unless she cooperated with the state. Jake was sending her threats. She didn’t want to help send Tremane to death row, but she also felt like he didn’t care about what he had put her and her kids through. Advertisement “I do understand now that he did care. I understand that he regrets it, and I think he wishes he could have told his brother no.” “It was the first time I felt like I was betraying him. I loved my kids with everything, and I had to choose.” Whatever anger Tremane may have felt toward Brandy has dissipated, he previously told HuffPost. “I always have some kind of love for her. We’ve been through a lot,” he said. “I can’t be mad at her for being in a position she never should have been in. That’s on me.” Advertisement The discovery of the secret plea memorandum felt vindicating for Tremane. Finally, he believed, there was clear evidence that the state hadn’t played by the rules. The courts hadn’t cared that Tremane’s lawyer was so badly impaired by addiction that he barely presented a defense for his client — but surely they would see that this warranted a new trial. “I was so impressed with Amanda,” he said of his lawyer. “I thought we had won. I thought we were going to get a new trial.” Advertisement There were reasons to feel hopeful. Drummond, the attorney general, pushed to slow the pace of executions shortly after entering office in 2023. Then, in an unprecedented move, he asked the Supreme Court to halt the execution of Richard Glossip and review the prisoner’s innocence claim. The Supreme Court vacated Glossip’s death sentence in February, a stunning outcome for a man who had survived nine execution dates. The high-profile debacle of Glossip’s case prompted several Republican lawmakers in deep-red Oklahoma to come out in support of an execution moratorium. To Tremane, it seemed like the people in charge were finally coming to see some of the flaws in the system. At the very least, it seemed like Drummond was willing to admit when the state had gotten it wrong. (Drummond has since flip-flopped on Glossip’s case: After agreeing to a plan for Glossip’s release if his conviction was vacated, Drummond is retrying Glossip for first-degree murder.) After the evidentiary hearing, District Judge Susan Stallings had 30 days to submit her write-up of her findings. But the judge didn’t write her own findings. Instead, she signed and filed the state’s version of events nearly verbatim, which asserted that Tremane had failed to prove the existence of a secret deal between the state and Brandy — and that even if such a deal existed, it wouldn’t have changed the outcome of his trial. Advertisement Stallings, the judge, had previously credited Fern Smith, the lead prosecutor in Tremane’s trial, with guiding her career when she worked in the district attorney’s office right after law school. For all the talk of reform, things were still very much the same. Stallings did not respond to a request for comment. The following month, Drummond asked the OCCA to schedule Tremane’s execution for Sept. 11, 2025. In recent weeks, court proceedings in Glossip’s case have exposed additional details about Stallings’ relationship to Smith. On Friday, Stallings became the third judge to recuse herself from Glossip’s retrial after Smith — who also prosecuted Glossip’s trial — testified that she and Stallings had traveled to Las Vegas, Spain and England together, according to a lawyer in the courtroom. Stallings testified in September that she had traveled to Spain with Smith in the ’90s, but did not mention the other two trips. Glossip’s team also uncovered a recent email exchange between Stallings and Smith that showed the two celebrating the state’s argument in Tremane’s case, which Stallings was overseeing. Advertisement “I thought you would like to see the order (unfiled version),” Stallings wrote on May 7, around the time she filed her findings, which nearly identically matched the state’s proposed findings. “Thank you so much!! Amazing!! I don’t know when I have seen a more thorough analysis and well-reasoned opinion,” Smith wrote of the findings, which cleared her of misconduct. “Which I can’t take credit for. It’s the proposed Findings from the AG’s office,” admitted the judge, who was supposed to be an impartial arbiter between Tremane and the state. “They did do an outstanding job.” Advertisement When Tremane arrived at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in 2004, death row prisoners were held on H-unit, a constellation of windowless cement cells. They spent 22 to 24 hours per day in their cells and were only allowed “no-contact visits,” separated from their loved ones by a thick layer of plexiglass. Being imprisoned on H-unit was like being “buried alive,” one prisoner told the American Civil Liberties Union of Oklahoma. Under the threat of litigation from the ACLU-OK, the corrections department agreed to move death row prisoners to A-unit in 2019, which came with small quality-of-life improvements. Most importantly to Tremane, they were allowed weekly contact visits. For the first time since his arrest, Tremane was able to hug his mom. When his first granddaughter was born, he was able to cradle her in his arms, a moment he never thought he’d live to experience. But by the summer, even those brief, joyful moments would be snatched away from Tremane. Around the time that Drummond requested the Sept. 11 execution date, prison officials found contraband phones in Tremane’s cell. Advertisement Contraband cell phones are a felony, but they are also ubiquitous in nearly every U.S. prison — often because guards sneak them in and sell them to people desperate for a tie to the outside world. The Oklahoma Department of Corrections said last month that it had seized more than 4,000 contraband phones in 2025 — roughly one for every seven people in its custody. Because contraband phones are so common, guards often look the other way or hand down light punishments when they see one. Contraband phones are an issue that is being “aggressively addressed at our facilities by the agency’s investment in new contraband detection practices and technology, and nationally by the federal government through legal authorization for jamming/signal interference,” Kay Thompson, public relations chief for Oklahoma’s Department of Corrections, said in an email. Punishment includes mandatory revocation of credits toward early release and mandatory level demotion, which impacts a prisoner’s pay and access to privileges like phones, televisions and recreation. There is also the optional punishment of disciplinary segregation. But for Tremane, getting caught with cell phones proved devastating. As punishment, he was moved back to H-unit, where he is allowed a single, one-hour no-contact visit per week and has limited access to a phone. These restrictions are in place longer than he is expected to live — meaning he may never get the opportunity to embrace his mom, his brother, his girlfriend, his sons, his nieces and nephews, or his grandkids again. Advertisement When social worker Jorja Leap visited Tremane on July 2 in preparation for his clemency hearing, she was alarmed by his apparent deterioration since their last visit in November. During their prior visit, Tremane acknowledged he might be facing imminent execution, “but he was hopeful and positive about whatever amount of time he might be alive,” Leap wrote in a report. But in July, he “was in despair and cried throughout the three hours we spent together.” He told her he had acquired enough pills to overdose and that he had tried to make a noose to hang himself. While Tremane was contemplating ways to end his own life, Drummond was at work trying to ensure the state would get the chance to kill him. With Tremane’s clemency hearing coming up, the contraband cell phones presented the perfect opportunity to make the case that he wasn’t a rehabilitated family man — but an unrepentant rule-breaker, undeserving of mercy. On July 15, Drummond emailed Lumpkin, the judge overseeing Tremane’s case, to secretly notify him about the contraband cell phones. He suggested, without evidence, that Tremane had used the phones to sell drugs, order a “hit” on another prisoner and communicate with his public defender and a county judge’s clerk. (In a subsequent email, Drummond clarified that the public defender Tremane had contacted was not part of his current legal team. The lawyer, who represented Tremane years ago, has since resigned from the public defender’s office.) Advertisement Drummond had taken the unusual step of referring the phone incident to state law enforcement officials, and he wanted the judge to quietly postpone Tremane’s execution to give the state more time to build its case before his clemency hearing. At first, Lumpkin appeared willing to oblige. He and the other judges on the OCCA planned to meet the following week to discuss execution dates, the judge told the attorney general. “Is that timing OK or is this something that will need attention prior to that time? Please let me know,” Lumpkin emailed Drummond. Drummond responded that the timing worked for him and thanked the judge. The American Bar Association advises both judges and lawyers against “ex parte communications,” or communication between a decisionmaker and an interested party without the other parties’ knowledge. This is meant to ensure fairness in the judicial process and prevent one side from gaining preferential treatment from the judge. Advertisement The evening after Drummond’s request, Lumpkin sent a follow-up, noticeably more formal, email. “I need to clarify that the Court cannot take any action or make any decisions based on proffered ex parte communications,” Lumpkin wrote. “The only matters the Court can consider are those matters properly filed before the Court.” But the attorney general didn’t want to formally request the delay. “Unfortunately, my office making any filing — even under seal — on this matter will likely tip off Mr. Wood as to nature of the investigation,” Drummond wrote. In other words, he didn’t want Tremane to have the chance to prepare a defense related to the cell phone allegations. “We would rather have a September 11 execution date than compromise the investigation through providing Mr. Wood notice of the investigation,” Drummond wrote. Oklahoma’s Code of Judicial Conduct requires a judge who inadvertently receives an ex parte communication to “promptly” notify the other parties to the case and provide them with a chance to respond. Lumpkin waited two weeks to notify Tremane and his lawyers about the communications and an additional nine days to provide them with the actual emails, which they later succeeded in getting unsealed. Advertisement When Tremane’s lawyers read the emails between Drummond and Lumpkin, they realized why Tremane was being punished so harshly for the cell phones, Bass Castro Alves said in an interview. “It was shocking to read that Attorney General Drummond prejudiced the court against Tremane while that same court was deciding whether Tremane deserved a new trial, and that Attorney General Drummond also enlisted the court in his effort to portray Tremane as a public safety threat to undermine his case for clemency without tipping us off.” The state has not charged Tremane with any crimes in relation to the contraband phones, which were first discovered in May. Bass Castro Alves asked Drummond in August and September to provide her team with all evidence supporting his allegations that Tremane committed criminal acts while on death row, as well as access to the phones and the information stored on them for independent forensic analysis. Without this evidence, “we have been hamstrung in our ability to independently investigate these allegations or to challenge them,” she wrote in her request to Drummond. Advertisement The attorney general declined to turn over the evidence, stating that because his office had not charged Tremane with a crime, he was not entitled to discovery. Tremane’s lawyers filed motions to recuse Lumpkin from Tremane’s case and to sanction Drummond. The OCCA denied both requests. Days later, Lumpkin wrote the OCCA’s decision upholding Stallings’ findings. Advertisement Tremane and his lawyers didn’t get a glimpse of how Drummond was prepared to use the phones to argue that Tremane deserved to die until Oct. 22 — the deadline for each side to submit written materials related to the Nov. 5 clemency hearing. In a series of bullet-pointed lists, Drummond included more than 100 points of evidence recovered from the phones that allegedly showed Tremane engaging in criminal activity or misconduct while on death row. Most of the allegations involved selling or using drugs. The most serious allegation is that Tremane directed a friend incarcerated in a different prison to arrange for another prisoner to be beat up. In the screenshots of the text messages included in the state’s clemency packet, Tremane described the target as someone who killed his female cousin. “Wood’s actions on death row in recent years, including distributing drugs and having another inmate viciously beaten, prove that death is the only way to ensure the safety of Oklahomans,” Drummond wrote in a press release, announcing his opposition to Tremane’s clemency request. Advertisement Tremane admitted to having contraband phones and, at times, “losing his way behind the walls,” he said. “Over the 23 years I’ve been locked up, I’ve done things that I’m not proud of and have made bad choices that I regret,” he continued. “But I’m not a killer.” He also said that the phones provided a way to communicate with his loved ones as much as possible during his limited remaining time. “If you had months to live,” he said, “Wouldn’t you take the risk and break the rules so that you could text your mom ‘Good morning’ every day?” It is a paradox of the clemency process that exceptional rehabilitation is a requirement for mercy. Yet death row prisoners are typically deprived of rehabilitative programs and held in torturous conditions. What’s the point of rehabilitating a person whose punishment is death? Advertisement Since 2019, some people on death row have been “afforded the opportunity to work on the units or in food service in a limited capacity,” Thompson wrote, noting that such decisions are made “based on behavior” of the prisoners. “Program referrals for all inmates are based upon an objective assessment tool, availability and security level. All inmates have access to religious services.” Tremane spent most of his incarceration in solitary confinement, which is recognized by the United Nations as a form of torture. His prison records show that he repeatedly asked for jobs and programming, but was denied because of his death sentence. “No programs available on death row,” a 2006 record shows. In 2008: “No programs assessed due to inmate serving death sentence.” 2010: “Offender has no assessed program needs due to his sentence.” Last year, Tremane organized a petition for death row prisoners asking leadership for a counseling group where they could have a “safe and confidential space where [sic] inmates can openly express and process their grief and receive guidance from trained professionals.” Their request was ignored. Of the 15 men who signed the petition, three have been executed. Advertisement “Attorney General Drummond is pushing for Tremane’s execution, not because Tremane killed anyone (he hasn’t, and the actual killer has confessed), not because the death penalty reflects the sentence the jury actually wanted for Tremane (it doesn’t, and the jury foreperson has said so before the Oklahoma legislature), not because he’s the most culpable (he’s not, the actual killer confessed and received a life sentence),” Bass Castro Alves wrote in an email. Advertisement “Rather, Attorney General Drummond is pushing for Tremane to be executed because Tremane has at times lost his way in prison, not unlike many of the thousands of incarcerated people discarded by the system, and made choices that he has come to regret. I’m hopeful that the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board will see the Attorney General’s tactics for what they are: A massive distraction from the powerful evidence that Tremane’s death sentence is unjustifiable and that his life is worth saving.” When I visited Tremane last year, we spent about five hours seated on opposite sides of a long table in the prison’s visitation room. He took responsibility for participating in the robbery that led to Ronnie’s death and expressed remorse for the pain it caused the victims, Brandy, Lanita and his family. He described the ways he had grown since the time of the crime and spoke with pride about the support he provides to his family. He was fiercely protective of his mother, an unwavering source of love. By August, he had visibly declined, his face gaunt and his eyes quick to fill with tears. Since he was only allowed one visit per week, he had to forfeit one of his few remaining visits with his loved ones in order to speak with me. Separated by bars and plexiglass, we had to lean in so close to hear one another through the holes in the wall that I could feel his breath. Advertisement There was no clock visible in the no-contact visitation area. Without warning, a guard approached the back door of the small holding cell Tremane was in. The hour was up. As we stumbled through hurried goodbyes, I stared at the relatively healthy 45-year-old in front of me who, if all goes according to the government’s plan, will soon be dead. I watched as he crouched down, his hands behind his back, to stick his wrists through the bean port for the guard to cuff. In my effort to bear witness to every second I could, I was left with a final memory of Tremane that is not dissimilar to the image he told me he wanted to avoid: his body in a position of surrender to the people who would kill him. Tremane has told his friends and family he doesn’t want them in the room if he is executed. He doesn’t want them to see him strapped to a gurney with a needle in his arm every time they close their eyes. He doesn’t want that image to be their last memory of him. Advertisement Most of the people closest to him say they couldn’t watch. “I can’t consciously sit there and watch someone kill my brother and there be nothing I can do about it,” Andre said. “I would feel like I’m failing my little brother because I’m his big brother. How am I not protecting him?” “And knowing that no matter how much I yell and scream and bash against the window and say, ‘It’s not right,’ there’s nothing that’s going to stop it. I can’t. I can’t.” Advertisement Brenden Wood, Brandy’s son with Tremane, built a relationship with his mom through letters, phone calls and visits during her incarceration. But the relatives who raised him blocked him from getting to know Tremane. When Brandy returned home, she took Brenden to visit Tremane so that the boy could form his own opinion about his dad. “I was tearing up, trying to keep my composure. It tore me up inside knowing that half the stuff I heard about my dad this whole time was wrong,” Brenden previously told HuffPost of his first visit with Tremane, which happened when he was a teenager. “A bunch of lies. They made him out to be a monster. Acting like someone can’t make a mistake and be forgiven.” Despite Tremane’s effort to shield his family from the memory of his execution, Brenden is adamant that he bear witness to the killing. An active duty member of the military, he had to request permission for emergency leave to travel to Oklahoma. Advertisement “If I were on my deathbed, I wouldn’t want the only thing for me to see is white walls. I would like to know that family is there,” Brenden said in an interview. “This is my way of showing it doesn’t matter what anybody else says about you, it’s not going to change my opinion of you. I am here for you.” Brenden continued: “I haven’t had nearly enough time to actually have a full relationship with him. This could be possibly the last thing I could do.” Brandy plans to wait outside the prison in the parking lot to drive her son home. “I know that it’s real, but I keep telling myself, ‘this isn’t real,’ because I don’t want it to happen,” Brandy said in August, tears streaming down her face. “I know that he will always have a place in my heart and I am so very thankful that we are blessed to have such a special piece of him — our son Brenden.” Advertisement “I can’t consciously sit there and watch someone kill my brother and there be nothing I can do about it ... I would feel like I’m failing my little brother because I’m his big brother. How am I not protecting him?” As the Nov. 13 execution date approaches, Tremane’s girlfriend and family members are alternating who gets to take the one visitation slot each week. On Oct. 4, Linda made the two-hour drive with Tremane’s sister-in-law Micky Winn-Scannell, her daughter Brooklyn Wood, and Tremane’s other niece Andreyanna Wood. The prison requires visitors under 18 to bring a copy of their birth certificate, but Brooklyn, 17, was previously able to enter with her ID. This time, though, a guard refused to let her in. Advertisement “Is there no way we can speak to somebody?” Brooklyn pleaded. “My uncle only has 40 days left to live.” The guards wouldn’t budge, so Brooklyn sat in the car with her mom in the parking lot until the visit was over. She had just gotten braces, and she was looking forward to showing Tremane. Winn-Scannell initially tried to keep her kids from Tremane, hoping to spare them the pain of growing close to someone who would be executed. Despite her efforts, they got to know him through letters and phone calls. Winn-Scannell eventually stopped trying to discourage the relationship once she saw how much Brooklyn benefited from being able to confide in her uncle. Advertisement Winn-Scannell worries how her daughter, who has previously struggled with self-harm, will cope without Tremane. During a recent phone call with Tremane, she recorded him saying, “I love you niece-y, mwah, mwah, mwah.” If he is executed, Winn-Scannell plans to use the audio to make Brooklyn a teddy bear with a customizable voice message. “If everything doesn’t turn around, at least she’ll have that,” Winn-Scannell said. Advertisement On Oct. 9, the day of Tremane’s 46th birthday, he was given a full-body physical. A doctor checked his vitals and put a tourniquet on his arm and leg to check the condition of his veins. They needed to make sure he was healthy enough to be killed. After the physical, he was taken to the visitation room, where he sat chained across the table from about a dozen prison officials and staffers. The warden read his death warrant, detailing how he would be killed. He took note of the paralyzing drug used — if he felt pain, he would likely be unable to express it. He was given his 35-day packet, paperwork directing him to choose his last meal, his list of witnesses (a maximum of five) and what he would like done with his body and property. The prison provided takeout menus from several restaurants in McAlester, including Big Macs BBQ, likely a reference to the Oklahoma State Penitentiary’s nickname. The menu includes dishes like the “Behind Bars Rib,” the “Jail Bird Smoked Turkey” and the “Life Sentence Tray,” although the latter exceeds the prison’s $25 allowance. (Thompson said that DOC “does not provide menus from any specific restaurant as options for inmates choosing their last meals.”) Advertisement The warden detailed what “death watch,” the final seven days ahead of the execution date, would entail. Tremane will be subject to constant surveillance. Any time he leaves the cell, he will be strip-searched. If he brushes his teeth, he has to return the toothbrush when he is done. The lights will never go off. It was an unsettling experience for him, sitting in that room, surrounded by strangers watching him learn the details of how he will die. “It makes you feel lonely,” he said. If you or someone you know needs help, call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org for mental health support. Additionally, you can find local mental health and crisis resources at dontcallthepolice.com. Outside of the U.S., please visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention.