Randy Krehbiel

Tulsa World Reporter

Get email notifications on {{subject}} daily!

Your notification has been saved.

There was a problem saving your notification.

{{description}}

Email notifications are only sent once a day, and only if there are new matching items.

Followed notifications

Please log in to use this feature

Log In

Don’t have an account? Sign Up Today

More than a century ago, in the late summer and early fall of 1923, government censorship and military occupation came to Tulsa.

The situation was not entirely analogous to recent events, threats and claims concerning use or misuse of authority and suppression of the First Amendment, but there are some rough parallels that touch on America’s long and ongoing debates concerning free speech, individual liberty and abuse of power.

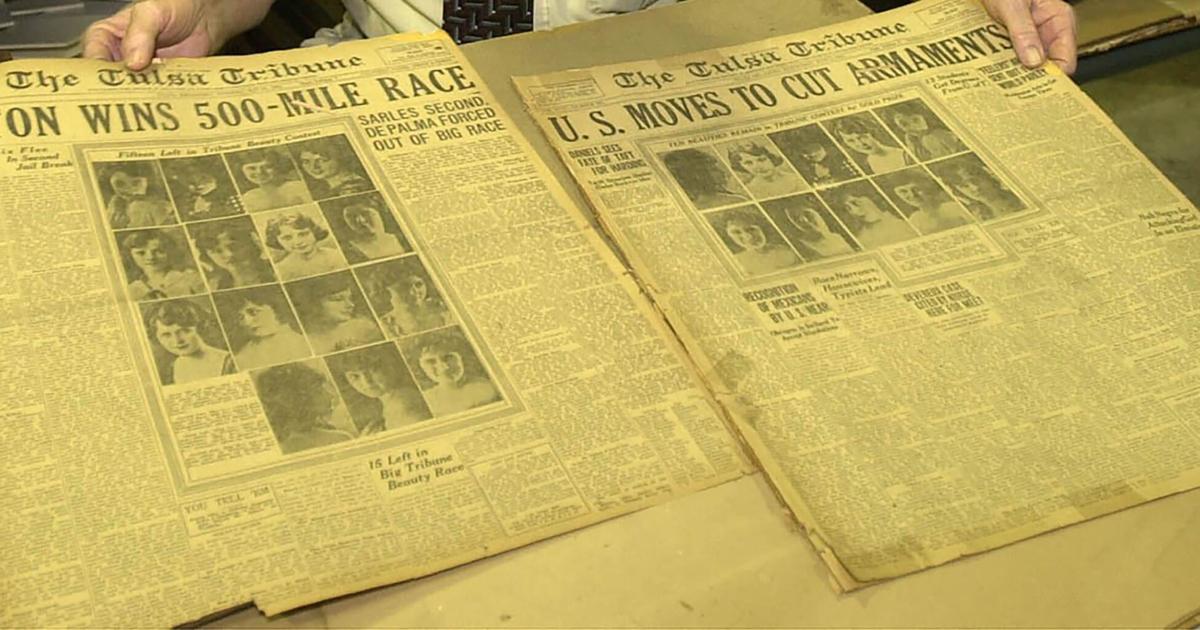

Instead of a late-night talk show host, an occupation that didn’t exist in 1923, Tulsa had newspaper publisher Richard Lloyd Jones and his evening Tulsa Tribune.

Instead of the Federal Communications Commission, which also did not exist in 1923, Tulsa had Oklahoma Gov. John C. “Jack” Walton.

The sorts of crime that President Donald Trump says prompted him to put National Guard troops on the streets of Washington, and threatens to dispatch to other cities, did exist in 1923 Tulsa, and in some abundance.

But that was not why Walton declared martial law in Tulsa County in 1923 and across the state a few weeks later, or why he put a National Guard officer in the Tribune’s newsroom.

That had to do with politics and the Ku Klux Klan.

Walton said he intervened because the Klan had taken over the city, and in that he was not wrong. Klan members swept the city and county elections in 1922, following Tulsa’s Race Massacre the previous year.

Two members were convicted of vote tampering in those elections.

More alarmingly, people were being snatched off the streets — often after being identified by law officers — and taken into the countryside, where they were beaten almost to death.

Some of these attacks were racial, but most appeared to target men and women suspected of such offenses as bootlegging, drug dealing, car stealing, unmarried cohabitation, speaking in heavy foreign accents, and what today would be called domestic abuse.

After a local judge complained about the physical condition of defendants being brought to his courtroom, the county bar association called for the removal of “two and probably four” police officers.

Mayor Herman Newblock defended the law officers and said the bar association was filled with “undesirables.”

Walton demanded the resignations of Sheriff Bob Sanders, Tulsa Police Commissioner Harry Kiskaddon and the three-member commission responsible for drawing up the county jury pool for, at the very least, protecting the “whipping parties.”

When all refused, Walton declared martial law and ordered a military tribunal to investigate and prosecute those involved in the whipping parties. He later extended martial law statewide, set up a military tribunal in Shawnee and tried to take over the Oklahoma City police department.

On Aug. 13, the day of the declaration for Tulsa County, the Tribune published a small advertisement at the bottom of page one. Under the heading “K.K.K.” it read: “Public initiation by Sand Springs Klan tonight; 100 candidates; prominent lecturer from New York City, Keystone road, one mile south and one-half mile west of Fisher.”

Exactly one month later, on the day the first criminal trial for an accused whipping party member began, a second ad of the same size appeared in the same location under the same “K.K.K.” heading.

It read: “He that putteth his hand to the plow and looketh back is not fit to enter the Kingdom of Heaven, nor ****”

The quotation, from Luke 9:62, was interpreted as a warning against revealing Klan secrets.

Walton immediately ordered a National Guard officer — whose civilian job was as a typesetter for the Daily Oklahoman — into the Tribune newsroom.

“The Tribune has persistently agitated against the course of the governor in the military probe into conditions in Tulsa County, precipitating the governor’s action,” said Walton’s chief aide, Aldrich Blake.

Reportedly, the Sept. 13 KKK ad triggered Walton’s action, although he later claimed it was because of the newspaper’s “tendency to inflame the public mind to hatred, rebellion and riot.” He did not cite any specific examples, though, except one connected with the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

Unknown to most of the state, Walton had put the Henryetta Freelance under military censorship more than two months earlier, supposedly for a church ad about an upcoming sermon on the martial law that had been imposed in Okmulgee County in June.

Censorship of the Muskogee Phoenix was threatened but never imposed.

Walton claimed the Tribune was a mouthpiece for the Oklahoma Klan, but aside from the two ads, it appeared to report on KKK activities much the same as the state’s other newspapers, including the more vocally anti-Klan Tulsa World.

The Tribune was highly critical of Walton, however, and that may be where the politics came in.

A former Oklahoma City mayor and former railroad worker, Walton was about as close to a Socialist as has ever been elected governor of Oklahoma. An amalgamation of Socialists, farmers and organized labor pushed him to victory by a plurality in the Democratic primary — which in 1923 was almost equivalent to winning today’s Republican primary.

Walton entered office with a big share of the Legislature and all of the state’s big money against him. His primary victory with less than a majority of Democratic votes eventually led to Oklahoma’s adoption of primary runoff elections.

Walton’s combination of populist politics, indiscreet cronyism, poor management and outsider status put him on impeachment watch from the moment he took office.

Walton probably really did dislike the Klan, but making a public show of fighting it also seemed like a good way of distracting the public.

Instead, it backfired.

The censorship of the Tribune lasted only 30 hours. Jones said the censor killed one paragraph, the contents of which were not disclosed.

Even the World, which tentatively backed Walton’s intrusion into local affairs and disdained what it referred to only as “an evening paper,” thought he had gone too far.

Martial law ended in Tulsa County on Oct. 7, 1923. Walton’s censorship of the Tribune and Henryetta Freelance were among the 22 articles of impeachment drawn up by the Oklahoma House of Representatives.

It was not among the 11 for which the Senate convicted Walton and removed him from office on Nov. 19, 1923.

randy.krehbiel@

tulsaworld.com

Get Government & Politics updates in your inbox!

Stay up-to-date on the latest in local and national government and political topics with our newsletter.

* I understand and agree that registration on or use of this site constitutes agreement to its user agreement and privacy policy.

Randy Krehbiel

Tulsa World Reporter

Get email notifications on {{subject}} daily!

Your notification has been saved.

There was a problem saving your notification.

{{description}}

Email notifications are only sent once a day, and only if there are new matching items.

Followed notifications

Please log in to use this feature

Log In

Don’t have an account? Sign Up Today