Copyright The Boston Globe

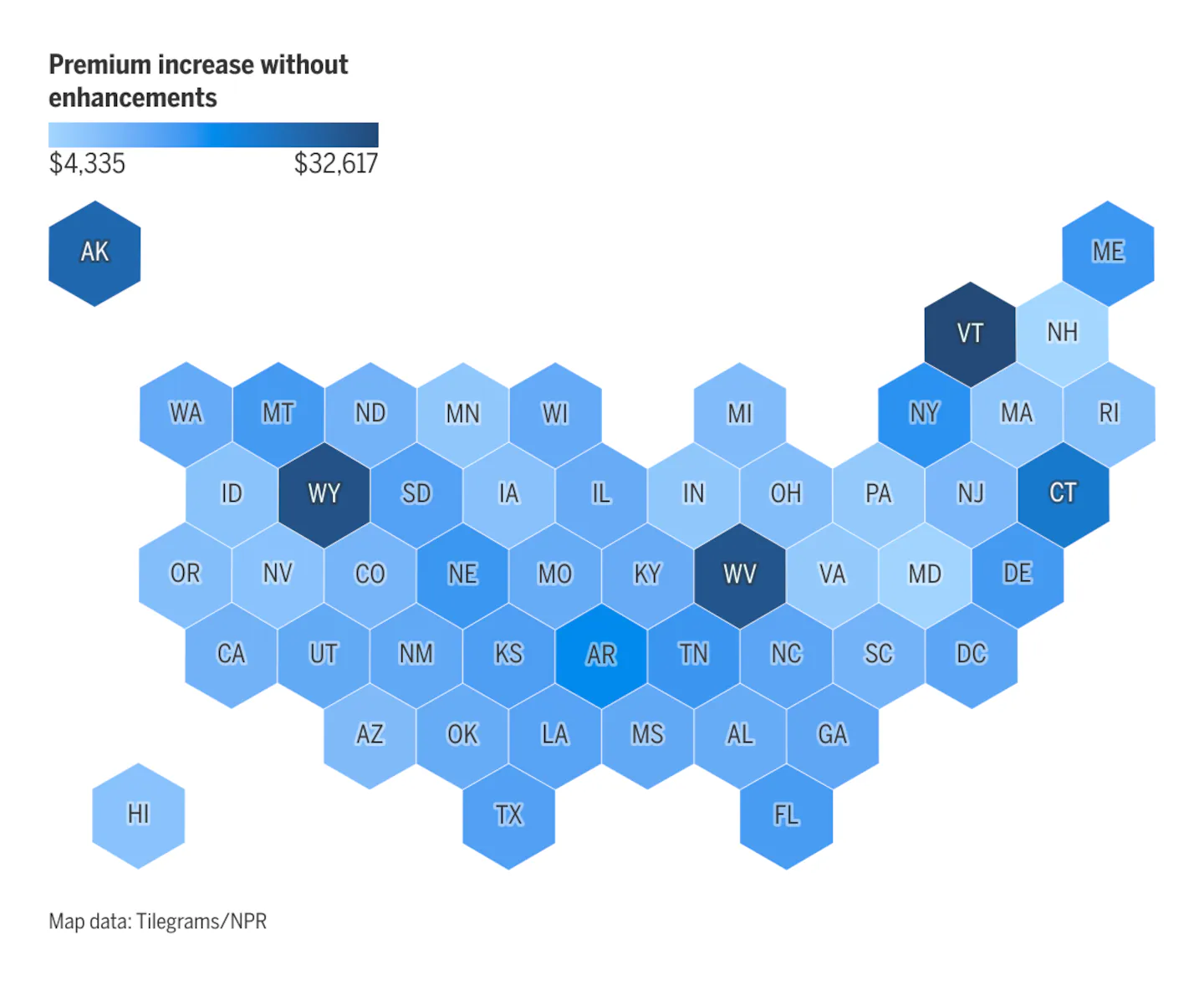

In Massachusetts, a family with the same income can expect premiums to increase by nearly $7,500. And a family with that income in New Hampshire — the New England state with the lowest price swell for that income bracket — will still see an average increase of more than $4,300. Variations in increases among states depend on factors including available insurance plans and the cost of care in that state, analysts said. These steep price tags are looking more and more likely to take effect as a gridlocked Congress barrels toward Saturday’s deadline amid the monthlong government shutdown. Democrats have sought to extend the Obamacare subsidies, which are aimed at helping Americans get affordable health care when they make too much to qualify for Medicaid. The issue has become a major sticking point in the negotiations to reopen the government. If those subsidies expire, people who get their insurance through the marketplace may be forced to splurge beyond their means or go without coverage at all, adding significant financial strain to an already flailing health system. Some states, including Massachusetts and Rhode Island, also impose a tax penalty on those who don’t have health coverage. “It’ll be a real gut punch for a working family in Massachusetts,” said Alex Sheff, senior director for policy and government relations at the health equity nonprofit Health Care For All. While the dollar figure hikes are shocking for families and individuals making around 400 percent of the federal poverty level, they’re arguably even worse for poorer people, health advocates said. A 45-year-old making $22,000 a year, or about 140 percent of the poverty line, will go from paying nothing in premiums for their coverage to paying over $780 annually in 2026. “When your income is $2,000 a month, going from paying nothing to paying 4 percent of your income is a real magnitude of difference,” said Jennifer Sullivan, director of health coverage access at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington, D.C.-based nonpartisan research institute. Hikes for those on the lower end of the income ladder are relatively uniform across the country. But in Massachusetts, a state subsidy will buffer some skyrocketing costs for adults with incomes at 300 percent of the federal poverty level or lower, according to Matt Buettgens, a senior fellow of health policy at the Urban Institute. The tax credits on the Affordable Care Act-established marketplaces — called “enhanced premium” credits — were enacted in 2021 and then extended through 2025 as part of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. President Trump’s signature budget bill that passed in July did not extend these subsidies again, setting up a battle between congressional Democrats and Republicans. It’s a fight at the center of the ongoing government shutdown, which will be at day 32 on Nov. 1, when the enhanced premium tax credits officially expire. Democrats refuse to open the government until the subsidies are extended. Republicans refuse to agree to that extension, at least while the government is shut down. Caught in the middle are Americans who are already struggling with climbing prices for everyday goods, while wages fail to keep up with inflation. Several New England states will see a major spike in their uninsured populations if the enhanced tax credits expire, an Urban Institute analysis said. In New Hampshire, the number of uninsured residents is forecast to increase by around 20 percent; in Maine, that number could increase by 15 percent. Massachusetts appears to fare better, with an estimated increase in the uninsured of about 3 percent. The state already has one of the lowest uninsurance rates in the country, with only 1.7 percent of residents reporting going without health insurance in 2023. States that have not expanded Medicaid are expected to see even sharper changes, as more people rely on the subsidized marketplace plans to get affordable coverage in place of Medicaid. Mississippi and South Carolina could see their rates of uninsured residents balloon by 65 percent and 50 percent, respectively. Not everyone will forgo their coverage because of the price hikes. Some will instead choose cheaper plans with higher deductibles and more out-of-pocket costs. “Medical debt is a big concern,” Sullivan said. “People don’t stop needing health care services when they can’t afford health insurance anymore.” The Affordable Care Act marketplace as a whole could suffer if people go uninsured or underinsured. Those who opt out of coverage are more likely to be young and in good health, leaving behind an older and sicker population that costs insurers more. Already, base premiums set by insurers for next year are higher because of the expectation that the enhanced tax credits will end, Sheff said. Even if the subsidies are extended after the deadline, analysts worry that with each passing day, people could opt out of their coverage because of the potential for price increases. Alternatively, if the tax credits do end and marketplace users don’t know they have to renew their coverage, they could get stuck with their current plan at an unaffordable price. “The ‘set it and forget it’ opportunity is hard for a lot of folks to resist, which just plays against the level of engagement that people are going to need to have this year to make sure that they don’t get burned,” Sullivan said. Open enrollment for 2026 begins Nov. 1 and ends on different dates in January depending on the state.