Copyright The Atlantic

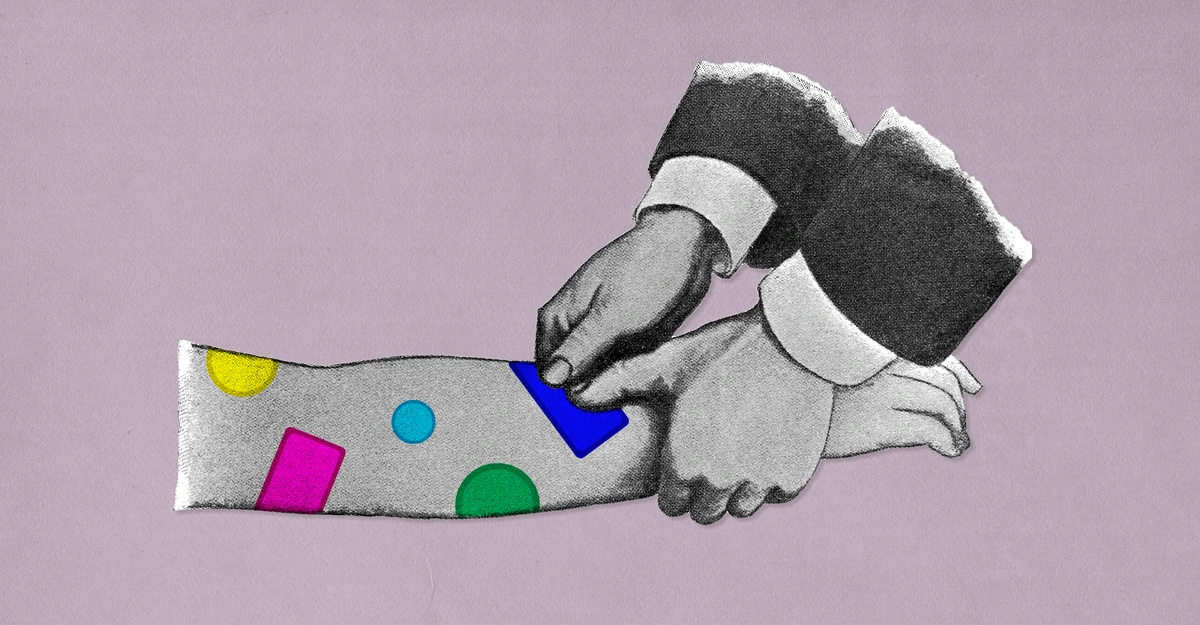

Last Thursday, in lieu of my afternoon coffee, I placed a sticker on the inside of my wrist. It was transparent, about the size of a dime, and printed with a line drawing of a lightning bolt—which, I hoped, represented the power about to be zapped into my radial vein. The patch had, after all, come in a box labeled Energy Boost. So-called wellness patches have recently flooded big-box stores, promising to curb anxiety, induce calm, boost libido, or dose children with omega-3s. Their active ingredients are virtually indistinguishable from those of the many oral supplements already hawked by the wellness industry. Whether the skin is a better route for supplements than the stomach isn’t entirely clear. But the appeal of wellness patches seems to have less to do with their effects and more to do with how they look. Wellness patches are generally pitched as an easier, safer way to take supplements. The website for The What Supp Co., a British brand that launched in the United States this year, describes its products as “super convenient” because users don’t have to take a pill or mix a drink—plus, they’re extra portable. That brand, like many patch sellers, laments the filler ingredients (such as corn starch and gelatin) that can show up in oral supplements, plus their digestive side effects; patches, it says, come with no such risks. The slogan for Kind Patches, which rolled out across Walmart locations last month, is “No pills. No sugar. No nonsense.” Half Past 8, a patch company that launched last week, says that its products sidestep the crash and comedown associated with some pills and gummies by offering a slow drip of wellness. Some brands also advertise that, unlike a pill, you can take a patch off when you’ve had enough. But that cuts both ways: I put another patch on my wrist yesterday morning, and it had fallen off by the time I got to the office. Most of the products are labeled as remedies for common complaints. Stickers from The Good Patch include Nite Nite for better sleep, Think for boosting focus, and Rescue for hangovers. Several brands sell patches that purport to mimic the appetite-reducing effects of GLP-1 drugs; you can buy them on the fast-fashion website Shein. And whereas traditional oral supplements tend to be marketed as vectors for specific compounds, leaving users to mastermind their perfect mix, patches are usually cocktails that advertise their active ingredients less prominently. Putting on The Friendly Patch Co.’s Relax and Let Go sticker really is easier than consuming supplemental forms of its seven key components, which include the herb ashwagandha, the neurotransmitter GABA, and magnesium. (Neither The Good Patch nor The Friendly Patch Co. responded to a request for comment.) Whether those ingredients will actually help you chill out is an open question, as is whether they can pass from a sticker into the bloodstream. The whole point of skin is to keep most things out of the body, and although some compounds are known to pass through the skin—nicotine and birth-control patches have been used for decades—little is known about the permeability of the many ingredients used in wellness patches. Some basic principles are well established: For compounds to pass through the skin, they need to be both tiny and fat-soluble; caffeine and vitamins A, D, E, and K all meet those criteria, says Jordan Glenn, the head of science at SuppCo, an app that helps supplement users optimize their intake. But other common wellness ingredients—such as coenzyme Q10, vitamin B12, folic acid, and zinc—require extra processing to permeate the body’s exterior, Glenn told me. My lightning patch was made by Barrière, whose co-founder Cleo Davis-Urman told me that the company uses a process called micronization to break down large molecules into particles small enough to enter the bloodstream. Micronization is a real technique used for pharmaceutical drugs, transdermal or otherwise, so it’s certainly possible that it could help big compounds pass through the skin. Yet this assurance, together with claims that patches offer a gentler and more sustained release than oral supplements, simply isn’t backed up by independent research; Meto Pierce, a co-founder and the CEO of Half Past 8, told me that the industry is “still developing in terms of published data.” “There might be claims of skin patches being more effective or more consistent, but we can just ignore that at this point because there’s no proof,” Elise Zheng, a health-technology researcher at Columbia University, told me. Dietary supplements aren’t regulated for safety or effectiveness by the FDA, and patches can’t even be regulated as dietary supplements, because they’re not ingestible. Wellness patches seem most useful for people who are already supplement enthusiasts—not only because they’ve already bought into the idea that ashwagandha works but because they take so many oral supplements that their mouth needs a break. “Pill fatigue” is a common complaint among the wellness set, Glenn said, though patch users notably still need to remember to apply their supplements. (Glenn also pointed out that patches might be more convenient for people who have digestive problems or difficulty swallowing.) An hour after I put on my sticker last week, I thought I felt marginally less groggy than usual. Maybe micronization really did make its B12 and folate particles tiny enough to seep into my skin. Or maybe the source of my energy was the sunny 15-minute walk I’d taken to acquire the sticker. By far the most noticeable impact of my thunderbolt was that I kept admiring it, as if it were a tattoo I’d gotten on a whim. Wellness patches are meant to be seen, as their fun colors and designs suggest. Ads for Kind Patches show wrists adorned with pepperoni-size stickers whose color matches their claim: Dream patches are a dusty blue, Energy is electric yellow, and Period Patches are, of course, bright red. The What Supp Co.’s patches are shaped like a w and come in lavender (for chilling out), kelly green (for detoxing), and pink (for beautifying). “We want the experience to feel joyful and intuitive, not clinical,” Ivana Hjörne, the founder of Kind Patches, told me. Kelly Gilbert, the founder of The What Supp Co., suggested that a patch on your skin could remind you to make other healthy choices throughout the day. It’s also free advertising for the company. Davis-Urman, Barrière’s founder, told me that with patches, customers are “elevated to brand ambassadors, because the product sparks conversation.” Before the rise of social media, personal wellness was a more private endeavor. These days, people post their run stats, sleep scores, and workout selfies; they wear fitness trackers and brand-name athleisure to the gym. This shift has reordered the priorities of personal health. It’s not just about taking care of yourself; it’s about taking care of yourself in a visible and socially sanctioned way, Marianne Clark, a sociologist at Acadia University who studies wellness culture, told me. Accordingly, wellness has also become a notably aesthetic pursuit—it’s no surprise that you can find patches to release skin-firming collagen or strengthen hair and nails. Conspicuous consumption has been part of the beauty industry since at least the 1920s, when Chanel No. 5 first hit shelves and became synonymous with wealth and luxury. (Wellness patches, too, don’t come cheap: My pack of 36 was $15, and other brands charge significantly more.) Social media has made the labor of beauty all the more visible. The online beauty community is rife with selfies glamorizing branded sheet masks and under-eye depuffing patches, photos called “shelfies” that showcase collections of expensive cosmetics, and images of celebrities sporting pimple patches in public. Brightly colored vitamin stickers similarly glorify the work of wellness. Not all wellness patches are beauty products, but many are meant to enhance appearance nevertheless. By 11 p.m. last Thursday, seven hours into the eight that my sticker journey was supposed to last, I was not sure whether I was less tired than usual. (Davis-Urman assured me that, although the effects of the patch differ for everyone, “cellular-level benefits” were occurring whether or not I felt them.) But I did get a tiny hit of dopamine when my husband noticed it and said, “Cute tattoo.” My lightning bolt also nudged me toward self-reflection, a pillar of modern wellness. Whenever I glanced at it, I asked myself: How do you feel? The answer was the same every time: Tired.