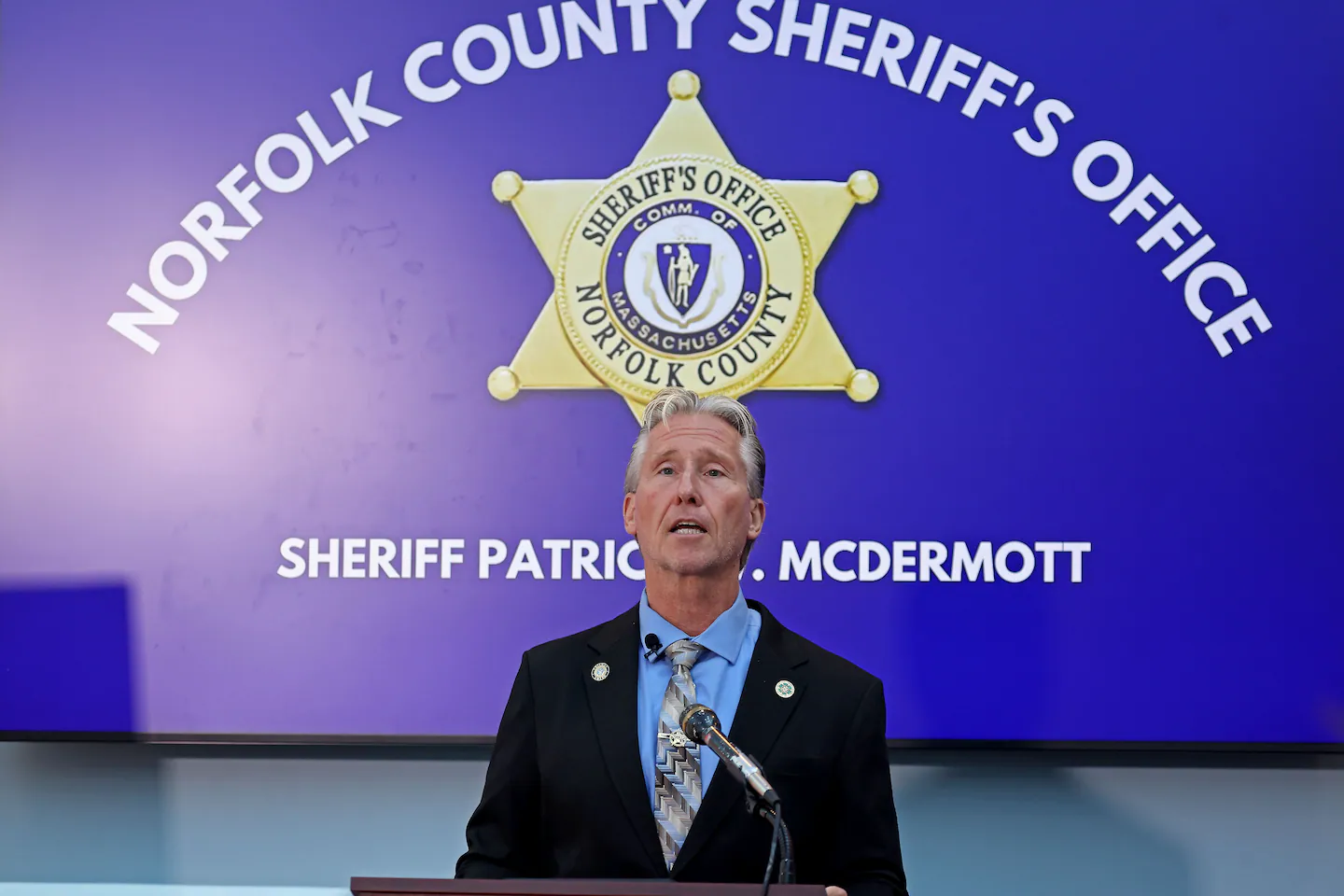

McDermott’s decision comes weeks after he agreed to pay $36,300 from his personal and campaign accounts under a deal with the Office of Campaign and Political Finance, which said he spent tens of thousands of dollars out of his campaign to bolster his “personal business future.”

McDermott promotes himself online as a public speaker and “mentor” to real estate investors.

The Globe reported this week that he tapped his taxpayer-funded office for thousands of dollars in online tutorials, including on how to grow a business, launch a podcast, and craft his own digital courses. He’s yet to create a course or podcast within the office, but he later began advertising an outside venture promising a “game-changing membership” that — for a $670 annual fee — offered advice to subscribers to help them take their “real estate business to the next level.”

In since-deleted pitches for the so-called Off-Market Millionaire Experience, McDermott also offered a four-week course on how to profit from “probate properties.”

McDermott, who was first elected sheriff in 2020, defended the office spending, telling the Globe there was no correlation between his outside interest in real estate and the taxpayer-funded charges, which he said would “enhance my leadership skills and improve the [office’s] operations.” He said his personal venture has generated “nominal, outside income,” has no employees, and consists of monthly Zoom meetings.

A spokesperson for the association said Wednesday that the state’s sheriffs are “collectively working to identify” a replacement for McDermott, who had been elected by his fellow sheriffs to serve a two-year term as president in January.

The Sheriffs’ Association is a decades-old state agency designed to “protect and enhance” the state’s 14 sheriffs’ offices, whose elected leaders make up its membership.

Its staff members are paid as state employees, and the association itself falls under the executive branch. The sheriffs’ offices themselves also technically function as state agencies, though they remain defined by their county borders, in which they operate the jails and houses of correction.

In a statement, McDermott said it was a “distinct honor” to serve as the association’s president.

“I am proud of the unified commitment we share to protect the public safety of our cities and towns, while also creating meaningful pathways to successful reentry,” he said.

The sudden change in the association’s leadership comes at a sensitive time for the elected law enforcement figures; a series of allegations against several sheriffs have cast their positions in a renewed, if unflattering, light.

Last year, Hampden County Sheriff Nick Cocchi, the association’s current vice president and immediate past president, was charged with drunken driving last fall. He later admitted prosecutors had enough evidence to convict him and had his case continued without a finding under a plea.

Then, in August, Suffolk County Sheriff Steven W. Tompkins, another past president of the association, was arrested and accused by federal prosecutors of extorting a cannabis company.

Tompkins has pleaded not guilty to the federal charges, but agreed to “step away” from his post at the request of Governor Maura Healey and Campbell, according to their offices.

He’s not the only figure in his department facing criminal charges. One correction officer has been accused of allegedly trafficking methamphetamine, and another former officer was charged this month with raping an inmate at the South Bay House of Correction during the summer.

Legislative leaders, concerned by reported budget overruns in the sheriffs’ departments, have also been scrutinizing their spending after Healey filed a bill seeking more than $160 million to cover their budget deficits.

A state commission established last year has separately been examining ways the state-run correctional facilities and sheriff-run county jails could be reshaped or even consolidated.

Several sheriffs have defended their offices, arguing that unlike appointed bureaucrats, they are accountable to local voters.

They also argued that their facilities — many of which are at half capacity — could take more incarcerated people from the Department of Correction, as opposed to the state-run DOC absorbing county-level jails and leaving sheriffs to handle other responsibilities, such as helping enforce evictions, serve summons, and carrying out other civil process duties.

Emma Platoff of the Globe staff contributed to this report.