By Mick Brown

Copyright brisbanetimes

“And that’s where the Elders, who have no armies, no budgets – our only asset is our experience, the little moral authority that we have – are very much needed. That is the challenge we face now: what is the most effective way for us to use that authority and the prestige the group has, in this very difficult moment.”

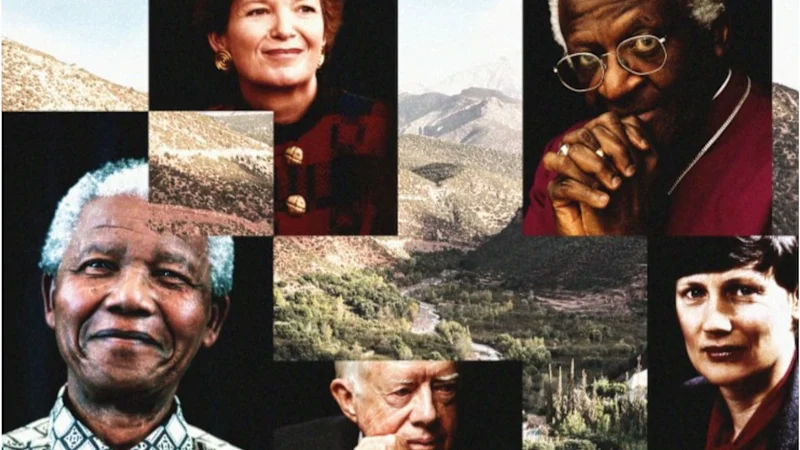

Santos was talking over dinner, on a terrace looking out to the Atlas Mountains, swathed in evening clouds. A quietly spoken, self-effacing man with a wry sense of humour, he was approached to join the Elders in 2019, shortly after leaving office as president of Colombia. “I was 67. I remember saying, ‘Well I’m not that old.’ It was explained that the concept of Elders in Nelson Mandela’s mind was that in South Africa, the elders are the wise men and women, not the oldest. I said, ‘OK, in that case I accept.’ ” He became chairman of the Elders last year, taking over from Mary Robinson.

While president, Santos negotiated the peace treaty with FARC by applying the principle of transitional justice, emphasising the recognition and protection of victims’ rights, including truth, justice and reparations. “We had been fighting a very dirty war, with no respect for human rights, and I changed that completely. Respect humanitarian law, respect human rights, even of your adversaries – I call them adversaries and not enemies.

“The former commander of the army taught me that, don’t treat the FARC as your enemies but as your adversaries. I said, what’s the difference? He said there’s a great difference: enemies you eliminate, adversaries you meet, and if you meet them in a good way, with a humane attitude, you can live with them for the rest of your life.

“Treat them as human beings – they have mothers, fathers, sons and daughters. That was a game-changer. It gave the army tremendous legitimacy. Instead of killing the FARC when they were wounded, they took them to hospital. And the commanders with whom I signed the peace treaty told me afterwards, that really changed the attitude of the guerrillas, not seeing the army as devils but as human beings also. That generated an environment that helped very much towards peace.”

The peace agreement was much criticised in Colombia, but Santos believes that was inevitable. “We say very often the Elders are not a group interested in winning wars but in preventing or stopping wars. And sometimes, to stop a war, you have to be a bit flexible. Some people think we gave too much to the guerrillas, and others say we were too harsh with the guerrillas. In my experience, the golden rule in many resolutions of a conflict is that you need to establish where you draw the line between peace and justice.

“How much are you, a country, willing to sacrifice in order to have peace? And no matter where you draw the line, you will always have people saying they want more justice, and others saying they want more peace. That’s why most peace agreements are easily criticised, and at the beginning they are unpopular. But as time goes by, people realise that it’s better to live in peace than to live in war. Justice is a principle that should always be present, but to what degree is the question.”

Amplification or negotiation?

As a group with limited resources – and a limited number of Elders – much of the discussion that I witnessed in Morocco focused on where they can be most effective in concentrating their efforts. To what degree should the Elders be an advocacy group, through a combination of public statements and working behind the scenes to influence different agendas, and to what degree should they be concentrating on private diplomacy in conflict resolution?

Alistair Fernie gives two examples of the Elders’ advocacy role. In 2022, in the wake of COVID-19, the Elders made it part of their strategy to become actively involved in the preparation for a better framework for international co-operation to deal with the next pandemic. Elders, Fernie says, were engaged in “behind the scenes” diplomacy to help negotiators from different parties find a way to an agreement. “It was touch-and-go,” he says. But in May this year, the WHO finally adopted the Pandemic Agreement for the prevention, preparedness and response to future pandemics.

“In the end, the US did not participate in that agreement after the Trump administration said it was going to withdraw from the WHO,” Fernie says, “but an agreement has been reached. So that’s a real tangible achievement. Helping a pandemic treaty is not in itself going to stop another pandemic, but it might make us better prepared to respond to it. It’s an area where so clearly the world is a very small place and none of us are safe until everyone’s safe.”

He cites climate change as another example. Elders pushed for several years, Fernie says, for “a loss and damage” component to the COP (Conference of the Parties) climate summit negotiations, a fund for small nations whose economy and in some cases – the Pacific island of Tuvalu, for example – very existence is threatened by climate change. That proposal was finally adopted at COP28, held in Dubai in 2023.

An unexpected talking point at that conference was the testy exchange in a video meeting between Mary Robinson, representing the Elders, and the COP president, Sultan Al Jaber, who is also chief executive of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, in which the then 80-year-old Robinson stood up to Sultan Al Jaber, telling him he was wrong about climate science and fossil fuels.

Answering questions later on whether she gets frustrated with countries talking big and then rowing back on commitments, Robinson said the Elders were in a position to call out such behaviour, because they are independent, have moral authority, “and need to do it. The UN doesn’t do it. Nobody else does it and so we do it across the board. Nobody is immune from that.”

The Elders have a responsibility to speak out, Fernie says. “Humility is an important part of the Elders. They don’t have power or claim to have power, and they don’t want power, so they can say things that will cause offence if they sometimes think it’s the right thing to do. And it’s undoubtedly the case that Elders’ views attack some vested interests, so of course we’re going to get criticised by those who don’t like what we say.

“Nelson Mandela predicted that in 2007, that you will be criticised. But he also said you won’t be seeking elected office or financial gain, so you will have the courage to just carry on saying what you feel needs to be said.”

‘We do it because it’s correct’

The question of private diplomacy is more delicate. The Elders tend not to talk of their successes, saying that to do so might compromise their access, although they cite one example of a successful intervention from the early days of the group, in 2008, when civil war broke out in Kenya, largely along ethnic lines, following the disputed results of an election.

Various attempts at mediation between the two warring factions had failed, until Kofi Annan, along with Desmond Tutu and Graça Machel, intervened, and over the course of meetings with the rival leaders in a game reserve, as one observer puts it, “basically knocked their heads together” until an agreement was reached to cease fighting and form a coalition government.

‘We don’t brag about what we do, and we should not brag about it. We do it because it’s correct.’Elders chair Juan Manuel Santos

But such conflict negotiations involving the Elders have more usually taken place away from the glare of public attention. These missions, Santos says, depend on trust and confidentiality – and trust, as he puts it, is “everything”. And if the Elders were to start talking about the discussions that have taken place, and taking credit for any successes, that trust would be eroded.

“We have a policy of private diplomacy and public advocacy. Sometimes you need to have visibility, but private diplomacy requires discretion. You don’t need to be delivering public statements,” says Santos. “We don’t brag about what we do, and we should not brag about it. We do it because it’s correct, but you don’t have to brag about doing something that is correct. In today’s world, hatred and jealousy and bad feelings are being fed by social media. If you start bragging about things, it’s counterproductive.”

To assume that simply sitting down at the table with a leader will lead to the end of conflict would be naive. Negotiations may not always produce immediate results, but wise counsel might come to fruition at a later time.

An Elders adviser gave me an example of accompanying one Elder engaged in just such a negotiation with the leader of a country. “They’d sought a meeting with that leader, and were pointing out the consequences of what he was planning to do, in a way he hadn’t understood or considered before. That’s hard to quantify and say the tanks stopped in their tracks, but there’s real value in that that may emerge in the longer term.”

Santos says: “The word ‘trust’ is crucial, and the way you earn trust is by not taking sides. Also, in my experience, the ability to listen, to understand the reasons why one side or the other are defending or attacking, the roots of the conflict, in order to try to address both sides to agree on some kind of common denominator.

“But if the neighbours in an asymmetrical war are not supporting a peace process, the peace process will most likely fail. If they are supporting it, the possibility of peace is much higher. If you compare conflicts to volcanoes, there are some that are active, some that are exploding and some that are relatively dormant.”

The exploding ones are obvious. Among the more dormant are Ethiopia, Libya, the Sahel region and Haiti looming as failed states. The question is, where should the Elders be concentrating their attention?

There are some conflicts which are too complex and intractable for a self-selected group, no matter how honourable their intentions, to make any difference, particularly when caught in the dilemma between honouring the principles on which they were founded and remaining silent in the hope of gaining access.

In 2022, shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, Santos and Ki-Moon met with President Volodymyr Zelensky to affirm their support for a peaceful resolution to the conflict rooted in justice and international law.

In 2015, six Elders had met Putin in Moscow to discuss a range of geopolitical issues including Ukraine. But following Russia’s invasion, Putin has refused a meeting after the Elders publicly called for a special tribunal for Russia’s crime of aggression.

“No leader likes that,” Santos says. “This is the permanent dilemma we have – sticking to our principles and making them known publicly, versus the private diplomacy of trying to solve the problem.

“We have been trying to see how we can help in bringing the two parties together to start some kind of negotiation. Many people and many countries have been involved in trying to do the same, so our margin of manoeuvres is rather limited, but our stand is: the sooner we stop the war, the better.

“But if the time comes and we have some access, we would talk to Putin with no problem whatsoever. In any negotiation, both sides have to understand that you don’t make peace with your friends. You make friends with your enemies.”

The mogul in the mix

Other than as the facilitator and a friend, Richard Branson has made a point not to involve himself in the running or governance of the Elders, while at the same time offering help and resources wherever it is needed.

Even before the launch of the organisation, in 2003, as America was preparing to invade Iraq, Branson, through the mediation of his friend the late King Hussein of Jordan, told Mandela that Saddam Hussein was willing to leave Iraq for Libya with his family, to help avoid the need for war, but wanted two Elders to fly out with him “so I can hold my head high”.

Mandela agreed to fly to Iraq if Kofi Annan, who was then secretary-general of the UN, and Thabo Mbeki, the president of South Africa, agreed to the plan. They did. But before Mandela could get to Baghdad, America invaded.

“It may have come to nothing anyway,” Branson told me at the Elders’ inaugural meeting in 2007. “But it was an example of universally respected Elders, working outside the conventional political process, who could potentially have made a difference.”

Such frustrations and “what ifs” are part and parcel of the Elders’ work. “It’s had some great successes,” Branson says now, sitting in the big tent in Morocco during a lunch break. “But like any organisation, it can be more effective going forward.”

Throughout the meetings, Branson sat quietly, listening intently to the discussions and scribbling in his notebook, only occasionally interjecting with a thought or a suggestion. That morning he had suggested that, given the number of issues confronting the Elders, perhaps it would be helpful to recruit a number of younger representatives who could both broaden the scope of the group’s work and take some of the weight off the existing members.

“One of the problems with the Elders is that they’re elderly,” Branson says. “We’ve got Elders who are 86 years old, so there are only so many visits they can do.” Annan, he points out, died in 2018 at the age of 80, following a trip to Zimbabwe for the Elders. “But if we can get a group of younger ambassadors, maybe not as well known, maybe ex-foreign secretaries, who could go to Palestine or the Congo, which desperately needs visits, and instead of having to look for three or four Elders to go on these trips, have one Elder and three ambassadors.” It was an idea they were considering.

The next meeting of the Elders is scheduled for October. But members of the group will be at the UN General Assembly in New York this month – at which all of their combined powers of influence and diplomacy will be brought to bear.

‘This is something since the time of Mandela that we are very clear about: that we should always say what we think is correct.’Elders chair Juan Manuel Santos

As the gathering in Morocco drew to a close, Santos deliberated on what the future might hold – and what the group might continue to achieve. “The biggest obstacle now,” he says, “is we have a set of values and principles that we believe in, and the world has been affected by a devaluation of those values and principles.

“What we think is our major strength, which is our moral authority, is not as appreciated around the world. Because even many leaders are less sensitive to criticism by people with moral authority.

“It is very sad, but we are very clear that we will never renounce our values and principles. This is something since the time of Mandela that we are very clear about: that we should always say what we think is correct. And perhaps the world will listen.”

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and Brisbane Times.