By Dr Tolulope Ogunmuko,Pulse Mix

Copyright pulse

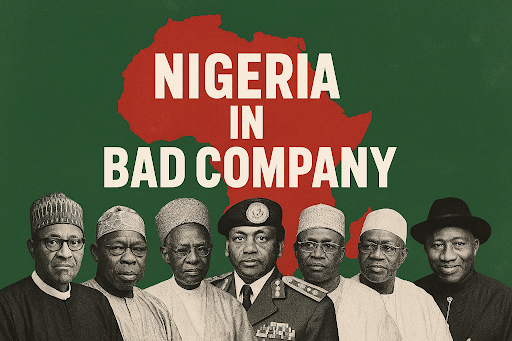

Nigeria prides itself as the “Giant of Africa.”

While there is no official declaration nor a precise year when this title was conferred, the moniker emerged in the early 1970s, when Nigeria blossomed as Africa’s wealthiest nation—especially after the 1973 oil crisis. The country enjoyed unprecedented growth, so much so that General Yakubu Gowon was quoted as saying, “Money is not the problem, but how to spend it.”

One is left to wonder: was it this very lack of ideas on how to spend our wealth that birthed the troubles bedevilling us today—exponential population growth without planning, corruption in procurement and governance, and decades of squandered opportunities? When the use of a thing is not known, abuse is inevitable. Perhaps this is why Nigeria now features prominently—sometimes even leading—in some of the worst global development rankings.

Let’s dive in to review the bad company we currently swim in.

Health, Education and Nutrition: The Human Capital Crisis

If a nation’s wealth is its people, then Nigeria is running on a bankrupt account. Today, we hold the unenviable record of the lowest life expectancy in the world—about 54 years—and the highest maternal mortality, with a woman dying every seven minutes during childbirth. I am shocked at this record, and I am quite certain many of my readers would be. It’s quite despicable that living in Nigeria is the greatest risk to life even greater than living in Afghanistan. These grim statistics are not the result of divine punishment, but of decades of underinvestment and policy neglect. Hospitals are under-equipped, health workers are underpaid and emigrating in droves, while primary healthcare—the bedrock of any system—remains weak. That horrible picture of the hospital in Kangiwa, Kebbi state easily summarises the ‘’state of art ‘’ care available in our general hospitals.

Education fares no better. Nigeria is home to over 10 million out-of-school children, the highest number globally. Classrooms are overcrowded, teachers poorly trained, and strikes by academic staff have become routine. Yet rather than confront these structural basic issues, there has been a plan to incorporate practical and technical skills like IT and entrepreneurship, and emphasize STEM education for primary and secondary students, beginning with the 2025/2026 academic session- this September. I mentioned on a X space – ‘’it is a policy somersault. You don’t have schools but you’re talking about what you’re going to teach them in schools’’.

To compound this crisis, Nigeria now carries the heaviest burden of food insecurity in the world, with over 31 million citizens facing hunger. In a land blessed with fertile soil and vast arable land, millions are trapped in malnutrition, children grow up stunted, and adults lose productive capacity. Hunger makes learning impossible, weakens the body against disease, and deepens poverty cycles. That such a basic need is unmet reflects not a shortage of resources, but the failure of governance to turn Nigeria’s natural wealth into nourishment for its people.

Taken together, these realities paint a damning picture: Nigeria ranks worst in global life expectancy and maternal mortality, leads the world in out-of-school children, and now tops the chart for food insecurity. These three “bad records” strike at the very core of human capital—health, education, and nutrition—without which no society can dream of meaningful development.

Infrastructural Decay

In electricity, Nigeria is the world leader in deficits: in 2023, 86.8 million people lacked access, the highest number globally for the third consecutive year. Only about 61% of the population had electricity and even connected households received an average of just 6.6 hours per day. While installed capacity is around 13,000 MW, only a fraction—roughly 4,000–6,000 MW—actually reaches homes, leaving millions reliant on costly fuel generators.

Roads tell a similarly sad story. Nigeria has approximately 195,000 kilometres of roads, but over half are in poor condition, particularly in rural areas. Adjusted for population and land area, road density is low, and Nigeria’s road network ranks well below global standards, leaving it in the same league as countries often considered less developed. Poor roads impede trade, increase transport costs and risks of mishaps, and isolate communities, making economic development slow and expensive. Nigeria’s rail network spans about 3,798 kilometres, placing it far behind other African nations like Kenya or Ethiopia when adjusted for population and economic size. Rail projects are expensive and slow: the Abuja–Kaduna line cost roughly $4.4 million per kilometre, while Ethiopia’s Addis Ababa–Djibouti electrified railway was completed at a lower cost per kilometre despite being double-tracked and modernized. This shows inefficiency in both planning and execution, limiting the impact of rail infrastructure on national development.

Together, these figures tell a story of stagnation. With unreliable electricity, crumbling roads, and an underperforming rail network, Nigeria struggles to move goods, sustain businesses, or provide basic services efficiently. This infrastructural decay keeps the nation in bad company, alongside countries often seen as “less developed,” and it is a major reason why economic growth and social progress remain painfully slow.

Governance and living standards metrics

Nigeria’s governance crisis is evident in the daily lives of its citizens. With a rank of 116th globally on the 2025 Chandler Good Governance Index, the country struggles with weak leadership, fragile institutions, and poorly enforced legal frameworks, placing it firmly among nations with deep governance deficits. Poverty is widespread: as of 2023, nearly 39% of Nigerians—about 87 million people—live below the poverty line, very much recognised as the poverty capital of the world. These figures are not most numbers; they represent millions of families trapped in cycles of hardship with limited access to opportunity.

Human rights protections in Nigeria are extremely poor. The country scores only 3.2 out of 10 on the Human Rights Measurement Initiative’s “Safety from the State” metric, signalling a high risk of arbitrary arrest, disappearance, torture, and other violations. Citizens are often forced to live as second-class residents in their own country, with internally displaced persons (IDPs) scattered across camps and temporary shelters—over 3.5 million people remain displaced, many without access to basic necessities. Stories of Nigerians fleeing to other African countries illegally- Ghana, Benin Republic, South Africa, Libya etc, seeking safety and opportunity abroad, have become all too common. NIDCOM has been returning them, hopefully the situation at home won’t make them wilfully go back to captivity.

Remember that young woman, Mercy Oluwagbenga, rescued from Libyan captivity? She was driven by away by extreme poverty, including lack of basic health care for her ailing mum. She eventually lost her mum to the cold hands of death despite that much suffering in Libya. A very sad story. One could perceive the regret in her voice, the sadness in her face and the broken heart with which she delivered her experience. Mercy’s situation highlights the extreme exploitation that citizens endure when their own country fails to protect them.

Dissent is frequently met with intimidation. Activists like Dele Farotimi face harassment and detention simply for speaking out, while political opposition figures such as Omoyele Sowore have endured repeated legal challenges. Sowore crosses boundaries particularly when declaring Tinubu as a criminal in his post on X. Although it is important to note that no court has declared President Tinubu a criminal, the environment of intolerance toward differing voices erodes confidence in democratic principles. Women, too, face systemic exclusion from political life, with Nigeria ranked 143rd out of 144 countries in women’s political empowerment in the 2025 Global Gender Gap Report. This severe underrepresentation reflects broader inequalities in decision-making and leadership.

The quality of life for ordinary Nigerians is alarmingly low. Ranked 135th out of 199 countries in the Quality of Living Index, the population contends with poor infrastructure, high cost of living, environmental degradation, and restricted freedoms. Taken together, these realities place Nigeria in bad company with countries often criticized for human rights abuses, governance failures, and social inequities—yet many citizens remain unaware of how closely they share these global “records.” The combination of extreme poverty, weak governance, limited freedoms, and social inequality stifles development and traps the nation in cycles of suffering. Until reforms are undertaken to strengthen institutions, protect human rights, and empower citizens—including women—Nigeria will struggle to move away from this “bad company” and towards a future of real development.

To be honest, you cannot expect development if you have the poorest metrics. It’s not surprising, these things are not magic. If Nigeria wants to break free, we must start by cutting the fat and ensuring efficiency. Look around: private jets, big cars and plenty escorts, unnecessary perks, and recently, the RMFAC even suggested increasing salaries for government officials who already eat fat and sleep on silk sheets. Meanwhile, the minimum wage of 70,000 naira can barely even take a worker from Ikorodu to Surulere or from Ologuneru in Ibadan to Orita Challenge round trip for a month. He must not dare have a car or run a generator. This is the reality of our everyday Nigerian. If we want to change, we need to trim unnecessary spending, stop enriching the already rich bureaucrats, and put the money where it matters—into the pockets of the people, not into luxury fleets or inflated government salaries.

Next comes prioritisation. Why are we building airports while people struggle with things that directly reduce their daily burdens? Imagine, having an airport in Ilisan Remo? Or building a coastal highway with 15 trillion naira – the total budget of many states put together. The government has to ensure proper Cost – Benefit analysis of projects and doing due diligence for public procurement to eliminate waste. Parents pay school fees for private schools because public schools are failing; they want quality education for their kids. And no, I’m not talking about the Enugu state -SujiMoto “schools” being investigated by the EFCC. Transport costs are another killer: people pay a fortune just to get from Lagos to Anambra to spend Christmas in the village. Imagine if federal and state governments subsidised buses, employed drivers directly like it’s done in many developed countries of the world. Instead of over bloating the civil service with unproductive staff, drivers and teachers are going to be bringing a lot to the table. The small joys of life—getting home safely, going from Lagos to Anambra for Christman holiday, sending your kids to school, running your business without constant headaches, screaming ‘’up NEPA’’ in unison- these are what makes most Nigerians happy.

And that’s how we have come to the elephant in the room: electricity. If power were fixed, affordable, and reliable, small businesses—barbers, tailors, vulcanisers—would thrive. Costs would drop, productivity would rise, and life wouldn’t feel like a daily survival drill. C’mon, let’s prioritise security of lives and properties, electricity, good schools, and low transport costs first. Only then can investors come in, only then can poor breathe. Every day the government celebrates “insecurity wins,” NSA chest-beating while the poor barely feel a reprieve. Let the people breathe.

Finally, we need to rethink our politics and governance structures. Changing federal or state governments every four years is killing continuity. Indeed, our problems are numerous, and it requires consistent efforts over time. This government barely had a year to focus before starting politicking. What Nigeria needs is a national development plan that survives administrations—crafted by consensus across tribes, religions, and regions—so every government, whether APC, LP, PDP, or whatever comes next, follows it. Some have suggested a single-term rotational presidency: NW today, NC tomorrow, and so on. I think it’s brilliant. It would reduce unnecessary politicking and allow every administration to focus on real development.

The truth is hard to swallow. By many global measures, Nigeria stands shoulder-to-shoulder with countries we often pity or mock. Our life expectancy is as low as Chad’s. Mothers die in childbirth at rates seen in Sierra Leone and South Sudan. We have more children out of school than Pakistan or Ethiopia. Over 30 million Nigerians go hungry, just like in Yemen or Afghanistan. Millions have no electricity, worse than Congo or even India. In governance, our name appears alongside Haiti and Zimbabwe. As the old saying goes, “Tell me your company, and I will tell you who you are.” Nigeria’s company in these global rankings is not the company of giants, but of nations we pretend to be better than. Your guess is as good as mine. We could drop that appellation and face nation building. We should start monitoring what to do with money and doing it well. President Tinubu , state governors and leaders across all strata should focus on helping its people.

The way forward, then, is clear: efficiency, prioritisation, and restructuring governance. Cut waste, focus on what genuinely improves people’s lives, and design political systems that enforce continuity and accountability. If we get this right, we can finally see affordable prices, better infrastructure, safer communities, and a nation where the average Nigerian feels progress in their daily life. But this will only happen when the right people are in power and they care about the many, not the few.

Written by Dr Tolulope Ogunmuko – Teeboi001@yahoo.com